“we are all uniquely made, and we need the liberation to live into that uniqueness”

Amy is joined by Lē Isaac Weaver and Melanie Springer Mock of Christian Feminism Today to discuss the state of gender relations in evangelical communities, Biblical Feminism, purity culture, and the dangerous politization of religious beliefs.

Our Guests

Lē Isaac Weaver & Melanie Springer Mock

Lē Isaac Weaver (they/them) is a creative and technical professional who assists artists, businesses, and nonprofits to create beauty and change with technology. Much of their work involves various aspects of spirituality and religion. Weaver is the author of numerous articles and reviews on Christian Feminism Today as well as the blog, Where She Is. They contributed the chapter ‘Genderful’ to the book Women Experiencing Faith. Weaver is a recipient of the Brian Eckstein Faithful Servant Award from the Q Christian Network.

+++

Melanie Springer Mock is an award-winning professor and author, a mother, a runner. an image-bearer of our creator. Melanie is a professor of English at George Fox University, Newberg, Ore. In 2009, she won the GFU Undergraduate Faculty of the Year award, and in 2015, she received the GFU Undergraduate Researcher of the Year award. She is the author or co-author of five books, including most recently Worthy: Finding Yourself in a World Expecting Someone Else (Herald Press, 2018). Her essays and reviews have appeared in The Nation, Christian Feminism Today, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and Mennonite World Review, among other places. She has finished 50 marathons, a dozen or more triathlons, and countless training runs. She lives in Dundee, Ore., with her husband and two teen sons.

The Discussion

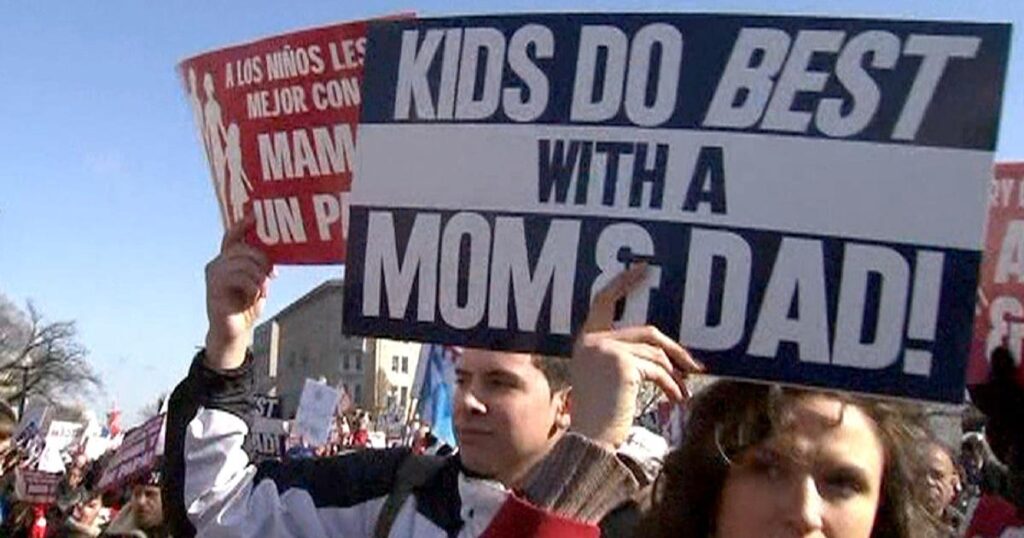

Amy Allebest: This past year, I have been noticing more than ever the enormous role that conservative Christianity plays in keeping patriarchy alive in the United States. From passing patriarchal laws, to supporting misogynistic strongmen as political candidates, to family Christmas photos with women’s mouths duct taped shut, I’ve been amazed at the surge of patriarchal norms that are being reinforced by the Christian right. I knew that there had to be Christian feminists fighting this trend, and I needed to know who they were. I found the organization Christian Feminism Today, and I was introduced to a whole universe of the most inspiring activism. I’m so excited to talk about the Christian feminist movement today with our guests, Lē Isaac Weaver and Melanie Springer Mock. Welcome, Lē and Melanie.

Melanie Springer Mock: Thank you so much.

Lē Isaac Weaver: Thank you for having us.

AA: I’m really, really excited about this topic. It seems like it’s coming up constantly on social media, and I don’t know if I’m just discovering these rabbit holes and these areas on social media with trad wives and really re-entrenching conservative gender norms. Maybe I’m just new to it, but it seems like it’s everywhere right now. So I’m very excited to dig into this. Let’s start out with an introduction. I’ll introduce you first, Lē, and then Melanie, and then I’ll ask you both to tell a little bit about yourselves personally after that.

Lē Isaac Weaver identifies as a nonbinary person and uses they/them pronouns. Lē is a creative and technical professional who assists artists, businesses, and nonprofits to create beauty and change with technology. Much of Lē’s work involves various aspects of spirituality and religion. Among the ongoing projects currently occupying their attention is Christian Feminism Today, The Bible and Beyond by Early Christian Texts, and the online Annotated Bibliography of Christian Science Academic and Other Literature. Lē has been involved with Christian Feminism Today since 2012 and currently manages their website and helps facilitate the group’s events and activities. Lē is also the author of numerous articles and reviews on Christian Feminism Today as well as the blog, Where She Is. Other publications include posts and articles on Voices of the Emergent Village and Patheos, and the website and print publications of Christians for Social Action. They contributed the chapter ‘Genderful’ to the book Women Experiencing Faith. Lē is a recipient of the Brian Eckstein Faithful Servant Award from the Q Christian Network.

Melanie Springer Mock is professor of English at George Fox University, an Evangelical Friends institution in Newberg, Oregon, where she primarily teaches first-year writing, memoir, and journalism courses. She is author or coauthor of six books, including Finding Our Way Forward: When the Children We Love Become Adults. Oh, that’s such a great title. Oh man. I have two adult children right now, so we’ll have to talk later. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Ms. Magazine, The Nation, Christian Feminism Today, Chronicle of Higher Education, Runner’s World, and Inside Higher Education, among other places. And she is a regular reviewer for Anabaptist World, Red-Letter Christians, and Christians for Social Action. She and her husband live in Dundee, Oregon, and have two young adult sons. She is a step-mom to two adults and Nani to three grandsons. In her free time, Melanie enjoys running, swimming, biking, knitting, and watching reality television.

I love it. This is wonderful. Well, welcome again, Lē and Melanie. Maybe we’ll just dive in in the order that I introduced you. And Lē, you can tell us a little about where you’re from and what brought you to the work that you do today. And then Melanie, you can pick it up right after Lē.

LIW: Sounds good. Well, I’m happy to be here. I love the podcast, so it’s exciting to get to talk to you. I was raised in the mainstream Presbyterian church, and when I say raised in there, we were there days each week, so it was a very, very important part of my life. And it was my grandmother and my mom, who both had the same name as I did, were kind of a little dynasty of laywomen in that very large church in our city, in Indianapolis here. Everything went swimmingly and the church was my safe place when school was difficult. And, you know, I’ve started to wonder if maybe it’s because at church I had to be dressed up like a girl and at school I was definitely and obviously gender non-conforming. And maybe at church it was a little less of that, I don’t know. It’s interesting to me. But when I came out as gay in 1979, that was a big problem back in the day. So I lost the church that I thought was going to be my home and my life, and I lost my safe place in the world. And it was a trauma that I didn’t realize was a trauma until many years later when people started talking about religious trauma. It was not a thing, you know, mental health care was not a thing and patriarchy was hardly understood, interestingly enough.

So after that happened, this was in ‘79, the next thing that happened was AIDS in the 80s. And Christians were not being very kind to gay people, so Christians were not on my favorite list of anything. And it was in 2002 that I got hired to do an audio engineering job for this group called the Evangelical Women’s Caucus. And I went into that job expecting there to be a bunch of church ladies, you know, and I was just going to do a really good job because when you’re the sound engineer and you do a really good job, nobody turns around to look at you. So I expected to be among people who would not like me, but I was just going to be really quiet and do my job and be happy. Well, lo and behold, this group was like nothing I had imagined in my life. Maybe it’s from being in Indiana or something like that, maybe it’s because there wasn’t much internet prior to this, though there was some.

But there were lesbians in this group, and I’m sitting there at the soundboard, and this gal stands up and she goes, “I just want to say that all the lesbians are going to have lunch together.” I about fell off my freaking chair. They seemed really nice before that. So I was like, “huh…” when she said that. And that was Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, who is one of the ultimate Christian evangelical feminists in the history of evangelical feminism. And I sheepishly went up to her and asked her if I could have lunch with them, because I had been a religious studies major in school even after the church got rid of me. And this conference was so fascinating, these people were just stunning that they were welcoming and there were lesbians and they were talking about all these really interesting issues in biblical studies that they were doing about women’s equality and stuff. I was hooked from then on. And they’ve really played a major role in my life ever since then. I got more involved with them in 2012, actually, kind of working for and with the organization. But that has been my entree to evangelical feminism, because they’re an evangelical feminist group started back in the seventies. And this year is our 50th anniversary, so I’m knee-deep in all the history of evangelical feminism, second wave right now, and learning about all these people and publishing information from our archives and all that. So that’s kind of my little story.

AA: Fabulous. Thank you, Lē. Okay, Melanie, you’re up.

MSM: All right. Well, just hearing Lē talk about the CFT folks, I would just echo everything about them. They’re an amazing, amazing group. I grew up as a Mennonite pastor’s kid and also did not conform to what it meant to be a Mennonite pastor’s daughter. I enjoyed playing sports, I hated wearing dresses, I got in trouble at school a lot. And I always heard that I was supposed to be a certain way because I was a girl, and I really resisted that because I wanted to be an athlete and I wanted to play football and wear jeans to church. I went to an evangelical college, and that was my first encounter really with evangelicals. I came from a pretty progressive branch of the Mennonites, and so I was stunned when I got to college and found that people could be Republican and Christian or people could be in the military and Christian, because that had not been the message I got growing up.

But it was at the evangelical college where the idea of biblical womanhood and how you were supposed to act and be as a Christian woman, those expectations were really front and center in my experience in college. And at the Christian college I attended and where I work, the idea of “ring by spring” was a huge deal, which means that you would find your spouse and get engaged by the spring of your senior year. And that didn’t happen for me, I didn’t even have any dates in college. And so I felt the weight of those expectations throughout my twenties. I was doing really fabulous things like getting my PhD in English, but because I had not gotten married and all my friends had gotten married, I felt like a failure and that something was wrong with me. Because in the evangelical tradition, when we talk about getting married and starting a family we use the language of God’s blessing. And so these friends were saying that they had been blessed by God in finding the one and blessed by God to have children. And that was something that I was not experiencing, and so I assumed that I had done something wrong in the eyes of God because I was not being blessed.

I finally did get married in my late twenties and moved to Oregon because I was going to get married, and then a position opened up at the university where I had been a student. So I have been teaching at a Christian university for 23 years now, and I’m considered one of the old folks there, which I don’t really like, but I’ve been there a very long time and have continued to feel the weight of those expectations of what it means to be a woman. My husband is also a professor, and early in my time at the college, when we decided to start having children, I got persistent questions about when I was going to quit to be home with my children. And nobody ever questioned my husband about that, even though I was on the tenure track and he wasn’t. So I felt those expectations and that I was disappointing people, the world, I don’t know, God maybe? Because I had chosen to stay and teach while I had my children.

And I am really passionate about this because I see my students feeling that same weight of expectation, that they’re supposed to get married and if they don’t get married they’re somehow a failure. That their careers, their calling from God needs to be secondary to their calling as a spouse and as a mother, and that women aren’t supposed to be outspoken or be leaders in the church. The women in my university still get that message growing up and from some quarters in the university. And so part of my passion of continuing to teach at a Christian university is to speak into their lives and to model for them that you can have both things. That you can respond to God’s calling to be a teacher or preacher, and you can respond to God’s calling to be a mother if that’s what you want to do, that we should have choices.

And I met Lē at the Christian Feminism Today conference, the first one I went to, I think in 2014. I went with a friend who had become involved in that university, and I was also stunned to be around so many faithful women who were boldly feminist with really strong voices, who helped me over the last decade see and understand my place in the world and see and understand God differently. And I’m really grateful that I met these women and that they continue to have a role in the evangelical universe.

AA: Wonderful, thank you. Well, this leads into the first question I was going to ask, and I was going to direct this question toward you, Melanie. What is meant by biblical womanhood? That’s a phrase that I hear in the evangelical context, and I think you alluded to some of those features of biblical womanhood, but could you spell out a few more of those defining features of that term?

MSM: Yeah, I can try. I’m really cynical about the term, actually. Biblical womanhood, I think, is a term that has been used to oppress women and silence women. And it reflects only a certain interpretation of the Bible. It does not reflect God’s truth in the Bible, which is a liberating message. Biblical womanhood is based on the idea that the Bible clearly lays out roles for women and roles for men, and that these are God-ordained roles reaching back to Genesis. And their understanding or interpretation of Genesis is that Eve, by being deceived by the serpent and then by deceiving Adam, reflects women’s inclination to be deceptive. That’s one of the things that they say, is that women are deceptive and they are tricksters and they will lie. So that’s the fundamental thing. That because we are daughters of Eve, we are deceptive and easily deceived. Because we are daughters of Eve, we need to be controlled by those who have biblical manhood. They wouldn’t say controlled, but by men, because men’s role is to be the provider, the protector, and women’s role is to be the nurturers underneath men.

LIW: They wouldn’t say controlled.

MSM: No, absolutely not.

LIW: They wouldn’t say it, but it totally is controlled.

MSM: Yeah, absolutely. So they see the entire Bible through that lens. The lens of men having the role of protector and provider and women having the role of nurturer sublimated under men. And you can go through every book of the Bible, they have a specific interpretation that reifies that notion of biblical womanhood or biblical manhood. I totally think it has been used for control. I totally think that it is a misinterpretation of scripture. And something that I’ve learned through my time at Christian Feminism Today is a liberating understanding of the Bible. Biblical womanhood and manhood really is just the opposite. It’s embracing who we are uniquely called to be. Because the other thing about biblical womanhood is that it supposes that we’re a monolith, that every woman is the same, every woman has the same gifts. But Letha Dawson Scanzoni, and Nancy Hardesty wrote a book in 1975–

LIW: They started it in ‘69, but it was published in ‘74.

Biblical womanhood is a term that has been used to oppress women and silence women. And it reflects only a certain interpretation of the Bible. It does not reflect God’s truth in the Bible, which is a liberating message.

MSM: Okay, called All We’re Meant to Be. And it was a liberating message that suggested the Bible tells a different story, tells a different narrative. And that narrative is that God created us all uniquely to be who we were meant to be. And that passage from that book has transformed the way I understand and walk through the world. With the belief that Scripture does tell me that I am uniquely created, fearfully and wonderfully made by God, to live into who God created me to be. That is not something that biblical womanhood would say. They would say that God has created all women to be a certain way and to follow certain roles.

AA: Well, that brings us to your activism, both of you. And like I mentioned, I ended up finding both of you through Christian Feminism Today. I wonder if you can talk about what that organization is and what you do in that organization. Lē, I’ll let you take the lead on this one.

LIW: Christian Feminism Today pretty much started out of second wave feminism, when that started back in the ‘60s. At the time, evangelicals were not all conservative at the time. It wasn’t politicized like it is now. You were evangelical, that was a certain set of beliefs about how you professed your faith and how you lived out your faith. There were liberal evangelicals, and you think about President Jimmy Carter, he was a more liberal evangelical. You could be a Democrat and be an evangelical and have different opinions about different things. Well, a group of liberal evangelicals got together around Thanksgiving 50 years ago, and they wanted to put out a statement called “Thanksgiving Statement of Evangelical Concern”, I think is the name of it, and you can look it up on Wikipedia. But of course, it’s 47 guys and 6 women at the time. You know, what would women have to do with anything at the time? It’s very hard for us to remember now or conceptualize when women achieved this degree of equality and could actually participate in the public square, right? It’s very hard for us to conceptualize how it was.

But whatever the case was at the time, they had this meeting, they invited a few people, and a gal named Nancy Hardesty was one of them. She was young and had been an assistant editor at an evangelical magazine called Eternity Magazine. There was another gal, Sharon Gallagher, who was the editor of Radix Magazine, which was another evangelical magazine. And a couple gals who were wives of men who were invited. So they put together this whole big statement. And the statement was about racial justice and economic justice, and on and on and on. And they never thought of it in the second to say anything about women, because why would you? Well, Nancy said to the guy sitting next to her, “You know, we should say something about women in this.” And he said, “Well, write something and I’ll try to get it in.” So she wrote on a freaking cocktail napkin a very lovely sentence or two about women’s equality, and it became part of that statement.

Now, Nancy was smart, and they decided they were going to meet the next year. So Nancy volunteered to be the secretary, and at the time women were always the secretary, so that gave her the power to invite people. The next year there were 50 women. And she started working with Letha Dawson Scanzoni, who Melanie mentioned earlier, and they tried to find all of the evangelical feminist women in the country, in different countries, and invited them all. They knew every invitation was precious, so they were very careful. And the next year with that group, they broke off into caucuses. So there was the Racial Justice Caucus and the Economic Justice Caucus and the Women’s Caucus, hence the name of the organization, the Evangelical Women’s Caucus. They had a great time all talking to each other because feminism was just coming into being.

And I cannot tell you what a revelation this was to those of us who were alive then. Women were subjugated, okay? The stuff you see on The Handmaid’s Tale, that women couldn’t have credit, all that, that was the reality! And so these women got together, they saw what was happening in secular feminism, and Nancy and Letha and Virginia – Virginia Raymond Mollenkot wrote her own book – and they started showing how the Bible supports the equality of the sexes and how the Bible supports women living into their calling, not having to play this certain role. And men could play whatever role they wanted to, and the organization really started taking off and reaching a lot of people.

That book, All We’re Meant to Be, people talk about that all the time about how it changed their lives. They could not go for this secular feminism because evangelicalism is all about the Bible, right? But as soon as that book came, all of a sudden there was a biblical case and they could live into it. And then we move into things like starting to think about inclusive language. Not always referring to God as “He”, which is huge because even now you hear people that can’t abide calling God “She”. It’s just wrong. Well, let’s think about what’s behind that. If it’s wrong to call God “She”, what does that say about women in general? There’s only one conclusion there. Nobody ever goes that logical step. So the Women’s Caucus started advocating for the use of divine feminine language to push that issue, inclusive language for everyone. And they wrote and spoke and went all around talking in evangelical and other settings over the next probably five or six years.

And then things started to get a little funky, because once you start thinking about the gender binary and how there aren’t these roles and it’s not a hierarchy and all this kind of stuff, you start getting into thinking about, what about gay people? Why is that so bad? Evangelical men predicted it would be a slippery slope to supporting gay people from supporting feminism. Supporting feminism was not that big of a deal, but as soon as they were seen to have slid down that slope and actually started saying, “gay people are human too and are capable of full fellowship with God and evangelicalism or anywhere else,” which was way ahead of its time, then they became very threatening to the culture. And so a lot of the advocacy of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus shifted into advocating for LGBT issues because they were scorned on other issues. A group broke off from them, they were called Christians for Biblical Equality. They stuck strictly to advocating for women’s equality within evangelicalism. Gay people were still bad, marriage was only between a man and a woman or celibate singleness. That was the only way you could be, but women were equal. So there’s a little history of that early part of the movement, and it just went on from there for both of the organizations.

AA: Perfect. Thank you so much. Melanie, is there anything you wanted to add to that?

MSM: No, I think Lē did an excellent job of telling the history of that organization. I’ve just been amazed at the way these disparate women came together, and they were all such amazing thinkers and writers and leaders in their churches and communities. When I went to the different gatherings, I would always be in awe of what these women were doing in their own communities.

AA: Wonderful. I had thought about asking you a question about different types of feminist work that’s being done today, and then we had a conversation before the podcast started. So you can answer this how you want, but I know that in my tradition, I’ve seen things in terms of radical feminism and reform feminism within the LDS tradition, but also broadly in secular feminism. You have those that are out there, wanting to uproot the system from the very root to get rid of everything and start over. That would be a radical, from the root approach, versus a reformed feminist that wants to work within the existing structure. In the LDS church, that might mean someone saying, “Well, let’s see if we can appeal to the men to see if they will allow women to pray in these general meetings or allow women to sit in the front of the congregation so that women have more visibility.” So, making smaller reforms that don’t upset the structure too much. I actually think both are valuable, and sometimes you need baby steps. But I wondered if there’s something analogous within the evangelical tradition where you have kind of the battering rams at the castle gates versus the gentler approach. Does that exist within evangelicalism? And either one of you could take this first.

LIW: So, I understand from the LDS standpoint how that would be the case. I guess if you had to make an analog to that within evangelical feminism, it would be like the difference between the Evangelical Women’s Caucus, which is a Christian feminist organization, and Christians for Biblical Equality, the group that split off from us to fit in more with a more traditional ethic of sexual behavior. Some evangelicals think they’re pretty extreme, but they have taken a more compromise type of position. If you were asking me how I’d break it down within evangelicalism, in the past there was oppressive evangelicalism, where the guys were totally in charge of everything and women’s roles were very limited. And so in many fundamental denominations, even like in the LDS church, I think there’s an analog to that. And then there’s the complementarian part of it.

I would make these four boxes oppressive, complementarian, which is the thing that says, “We love women and everything’s fine, but this is their role and they have this role to complement the men’s roles.” It’s a little gentler than the oppressive thing, yet still all about control. And then there’s egalitarian, which is what I would classify Christians for Biblical Equality. “Women are equal, but we’re not going any farther than that.” And then you get to Christian Feminism, and they would be radical people. And the point with Christian Feminism is that all divine images are divine images and should be recognized as being equally valid in the eyes of God. And that is no matter what you are or what you do or what gender you are. So it’s a big step past there, and that would be radical. But I think in evangelicalism, I don’t know if Melanie would agree, I think you really have to chop it up into a few more boxes.

MSM: Yeah. That language is very much familiar to me. And I would even separate it out further, that you have complementarianism and then you have soft complementarianism, which really is just complementarianism but nicer, I guess. Still saying that the women’s roles are very much defined as different from the men’s and they complement each other, but people act like soft complementarianism is not as oppressive as complementarianism. But when you’re saying that women have to live into certain roles, even if you say it nicely or act nicely about it, it is still oppression.

the point with Christian Feminism is that all divine images are divine images and should be recognized as being equally valid in the eyes of God

LIW: I think the thing you have to understand with evangelicalism is there is such a focus on Biblical inerrancy. Now, we could sit here and think about biblical inerrancy and say, “Come on!” Because, I mean, there are contradictions, there are things saying different things about the same thing, you know? And we know how much is interpretation based on where we are at the moment, and let’s not even get into the fact that there were over 200 documents being circulated right after the time of Jesus. And somebody came along and said, “we’re going to use these 27,” excluding all the ones that were in any way feminist or promoted female leadership or, you know, social justice kind of behaviors. It’s all been crammed into this gender binary hierarchy, all this kind of stuff.

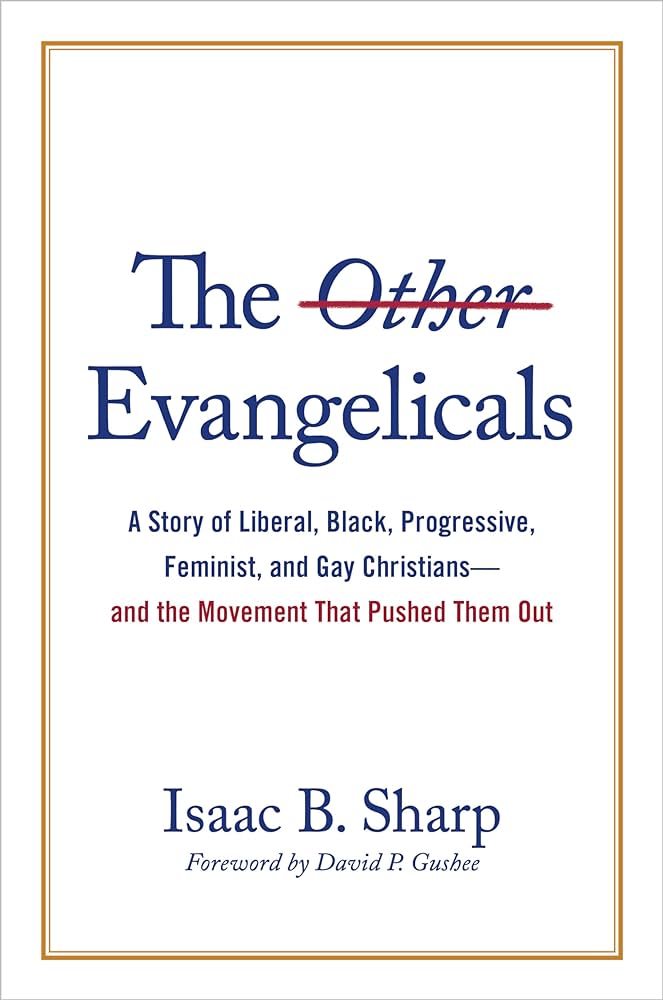

But biblical inerrancy, in order to solidify this biblically inerrant position, you have to have a fence and you have to keep making that fence bigger, taller, containing a smaller and smaller group, and those are the people who follow the Bible. And Isaac Sharp has written a great book that’s called The Other Evangelicals, and it’s a book about the evangelicals who over the years have been gatekeepered on out. So we’re down to this group now that we identify so strongly with the Republican Party and anti-abortion and all this kind of stuff. That’s what they’re left with now because they’ve chopped everybody else out. They’ve chopped out the Christians for Biblical Equality who are advocating egalitarianism. They’re out. That’s not what the Bible says.

So it’s really fascinating the extent to which evangelicalism relies on that. Now, people like Letha Dawson Scanzoni, Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, they called themselves evangelical until they died. They didn’t want anybody taking that word away from them. They stuck with the old meaning. The rest of us, meanwhile, we’re looking at what the word evangelical means in contemporary culture and saying, “Can we please stop using that word?” Because people approaching the organization, of course, would get the wrong idea about what we’re all about. See, I get animated about this.

AA: I love it!

MSM: I think that’s such a great description of the ways that gatekeeping has created a smaller and smaller group. And I think right now the gatekeeping has gone so tight that the only real evangelicals are the Christian nationalists and everybody else is being excluded from that. I mean, I’ve spent way too much time on Twitter or X or whatever, and I’ve seen that play out on who is in and who is out. Even six or seven years ago, a woman like Beth Moore, who was probably the queen of evangelicalism, writing Bible studies and is certainly a complementarian, is now out. She is not part of evangelicalism anymore because she deigned to question Trump’s Access Hollywood tape in 2016 and said that as a person of faith that she could not support something like that. So she’s out now. And if you follow some of our discussions on Twitter, she is reamed by other folks who say she’s not a Christian, that she’s a heretic. It’s just crazy to me, because this is Beth Moore we’re talking about. She is Mrs. Bible, really. But now she’s on the outs, because the gatekeepers have said that to be an evangelical you have to be in support of Trump and Christian nationalism and all the accouterments that come with that.

LIW: The minute you push back, the attacks are just vicious and come at you. I think Rachel Held Evans was a prominent evangelical feminist at the end of her life. And she started off a lot softer and she was okay with them for a minute, but as soon as she decided that gay people weren’t agents of Satan, she was out. With all her work that she had done, and that was before it got so it is. And I think the thing, Melanie, I’m sure you’ve thought about this, with some other denominations of Christianity, if you don’t believe exactly like them you can still be a Christian. You’re not out of the club, you’re just maybe a little misguided, but you’re still in the club. But evangelicals now, if you’re not adhering to their rules, then not only are you out of the club, but you are evil. You are an agent of evil. And I don’t know that there’s anybody that can argue that that point is incorrect. That’s a dangerous situation when you dehumanize everyone who’s not adhering to your beliefs. But that’s where we are.

AA: That’s just tragic, and I imagine it’s so frustrating to people of faith who do view their evangelicalism, their Christianity, as a relationship with Christ. To have that going on must be incredibly frustrating. I’m curious how that happens. As a point of comparison, in my context, if you do have someone who’s speaking out vocally and goes too far outside of the doctrine, we have a very formal system that’s maybe more like Catholicism, where you would get excommunicated. How does it happen within evangelicalism? Do you get excommunicated or do you get shunned by your congregation? How do you feel that process of getting pushed out? What does that look like?

LIW: That’s an interesting question, isn’t it, Melanie?

MSM: Yeah, that’s a great question. I can talk about it in the context of what I see on social media. Maybe two months ago the trailer for the new documentary that Rob Reiner has produced came out, and it was about Christian nationalism. And there were people in the evangelical world like Phil Vischer, who did Veggie Tales, and Russell Moore, who was the president of the Southern Baptist Convention, Kristin Du Mez, who wrote Jesus and John Wayne, they were all in this movie. The trailer came out, and because they were criticizing evangelicalism and Christian nationalism, the piling on that occurred on social media, both explicitly and in the direct messages that these folks got, that was where the line was drawn. They were clearly agents of Satan because they had deigned to be in this movie. I saw it playing out in some of the publications that come out of the far right, completely eviscerating these folks, people mining their tweets to find the tweets that put them in the worst lights and dredging those back up as a way of saying they are out, they’re not part of this fold anymore.

LIW: I think the difference is that LDS is one denomination, and the Roman Catholic Church is one denomination, so you can be excommunicated. It’s important to remember that in what’s considered evangelicalism, it’s become more consolidated now, but it’s more a loose confederation of different kinds of sects or churches that even call themselves evangelical. I mean, you can be kicked out of the Southern Baptist Convention. And there are a couple or three churches that, oh my God, had women as teaching pastors and that’s really bad stuff. So they kick them out of that. But really what happens is the demonization. It’s different. There’s a demonization, of course, that when you get excommunicated people who are still in the LDS Church are supposed to be careful about associating with you and all this kind of stuff. It’s much more cult-y with evangelicalism these days. Much more cult-y, and it expresses itself in a cult-y way. When you’re in a cult and you leave, whether it’s Scientology or any one of these other numbers of things, you become evil. No one is to associate with you at all, for any reason. This is what’s going on with evangelicalism. And I do honestly believe it’s becoming more and more cult-y all the time in exhibiting more and more of these cultish behaviors and interactions with the culture at large.

AA: Well, the next question I was going to ask, and this is directed to you, Melanie, because I know this is an area of expertise for you, is about purity culture. And I wonder if this has anything to do with the topic that we were just talking about in terms of gatekeeping. Can you tell us about purity culture in all of its many wondrous iterations?

MSM: Yeah, yeah. It’s something that I could talk about for hours and hours because its tentacles are so deeply entrenched in evangelicalism, both in terms of deciding who has the purity of thought and purity of etiology, and so can be part of the inner circle. More broadly, purity culture is considered within its sexual context and the evangelical sense that women especially are called to be sexually pure until marriage. And that level of thinking plays out both in how women are treated outside of marriage and how they are treated inside of marriage. And there’s an entire evangelical apparatus that has been built up around purity culture. It’s also commodified, meaning that young girls are given purity rings by their fathers as a promise that the father will guard the daughter’s purity until she can be married. And there are purity balls, it’s a weird thing, it’s like a wedding ceremony where the father makes a vow to the daughter that he will guard her purity until she’s married. With the assumption, of course, that she will be married, that that’s the trajectory that any girl will take. There are books and t-shirts and this enormous apparatus meant to cultivate a girl’s sexual purity.

And that plays out that boys are held to a different standard. But girls are also told that they need to remain sexually pure and they need to guard the hearts, not only of themselves, but of others, the men or the boys in their midst, meaning they should dress modestly because if they do not dress modestly, they may cause their male peers to stumble sexually. And it will be on them rather than on the men for thinking sexual thoughts. So it puts women in all kinds of binds. And it creates these two levels of personhood, really. So that women are always going to be damned because they have to guard their own sexuality. And if they stumble, if they have sex outside of marriage, that’s their fault. And if they’ve tempted a man to have sex with them outside of marriage, that’s their fault. It’s not the men’s fault. I see this playing out with my students all the time and the ways that they’ve grown up. What they’ve been allowed to listen to, what they’ve been allowed to read, what they’ve been allowed to wear. And I even see it in some of the rules of my university. Luckily, there are a number of women who have been really vocal at pushing back against those rules. But for example, for a long time at the university fitness center, girls were not allowed to wear just jogging bras. They had to wear a t-shirt over their jogging bras. But guys could wear these shirts that showed almost everything because it wasn’t their problem if somebody got tempted, it was the girl’s problem.

So it’s like these two levels of personhood, and girls are always going to be put in this place of being the temptress and also being tempted sexually. And that creates all kinds of problems, like young people at my university getting married before they’re ready because it’s better to marry than to burn. It’s actually getting married before they’re ready and not having any experience with sex and all kinds of the dysfunctions that come with lacking sexual experience. I just listened to this great podcast called Pure White, and it’s about the ways that purity culture is also racialized so that white women are the holders of purity, they’re the ones that cultivate the sense of virtue and morality. And then that is held against Black men, especially, and has been used to weaponize or to cause Black men to be lynched, like Emmett Till is an example of that. So there’s this racial component as well to purity culture that I don’t think we’ve talked about enough and that needs to be part of our conversation.

I just did a conference presentation on purity culture and how it relates to Moms for Liberty and other Christian nationalist groups who are using purity culture and weaponizing it as a form of creating change in school districts and school boards across the country. So they are conveying the sense that the Moms for Liberty, or white women, are the holders of purity for their communities. And therefore they will decide what books can be read in different communities, and they’ll at least decide what kind of curriculum can be taught in different communities because they want to keep the children of their community pure. But what purity means to them is that Black children can’t read books that have Black protagonists. It means that LGBTQ children can’t read books that have protagonists that would be like them. So I think purity culture roots are very deep, and it’s playing out now in Christian nationalist movements across the country, and it certainly played out in my own community.

LIW: Oh, that’s such a great observation. Nicely, nicely done. I’d add that one thing that purity culture is especially good at doing is keeping sexual assault and sexual abuse under control, unknown, under the table, because the shame is so intense that you would not report anything like that. You’re supposed to have ultimate control, right? Because you’re supposed to dress modestly, it’s all in your hands, right? None of it’s in your hands. And it just keeps the sexual assault and sexual abuse under the table so everyone can pretend it doesn’t happen. I hardly know any women who grew up in these extremely patriarchal evangelical fundamentalist settings that haven’t experienced some form of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or sexual abuse. It is rampant.

AA: And like you said, it seems like if you’re kind of indoctrinated from the time that you’re little that it is your responsibility, then you would automatically blame yourself.

LIW: Absolutely.

AA: You would victim-blame yourself and you wouldn’t want to tell anyone because you think that you’re the one at fault, right? Oh, that’s just heartbreaking.

LIW: 100%. Isn’t that some kind of double bind?

MSM: Yeah. And I think it’s actually a systemic problem at places like Liberty University and Patrick Henry College. Moody Bible College journalists have done investigative pieces about these universities that have purity codes and the way sexual assault at those universities is downplayed. Girls or women will give Title IX reports to the administration in these schools and they push it under the table. They will punish the girls rather than the men, or the women rather than the men. It’s just rampant and causes so many issues.

I hardly know any women who grew up in these extremely patriarchal evangelical fundamentalist settings that haven’t experienced some form of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or sexual abuse. It is rampant.

AA: One other problem that I’ve seen within, again, my own faith tradition and my sample of friends is that even if something tragic in terms of sexual assault doesn’t happen, even a best case scenario where a heterosexual couple marries, even having a normal and joyful sexual relationship is really hard. If you’ve been taught that your identity is purity and that purity equals virginity and being asexual, then suddenly, literally overnight, trying to become a sexual creature can be really, really difficult. Especially for women, for some men too, but especially for women to make that flip. And I mean, we’re keeping Mormon sex therapists in business because women just struggle with it so much. Have you seen that in your context also?

MSM: Yes. We just hired somebody in the communications department who’s coming next year, and she does research on purity culture and sexual dysfunction. And fascinating research, like how much sexual dysfunction there is, how much pain women report who have been in a purity culture and how their experiences with sex are very painful because of all the baggage that they’re carrying alongside these relationships they’re trying to form, even within the context of married sex.

LIW: I have a friend who was in CFT and who’s written an evangelical-oriented book about Christian feminism. And she’s actually a women’s pelvic floor therapist, and one of the main things that she treats are these sexual dysfunctions. And she will tell you it comes right out of all this programming. Where all of a sudden you’re supposed to be able to relax stuff that you spent your whole life freaking out about, ashamed of it, and the actual physical problems that are caused by that are very interesting.

AA: Yeah, that makes sense. I have to revisit, I was just kind of gesturing, for people who aren’t watching the video, gesturing that my mind was blown when you were talking about book bans and how that is another manifestation of this purity culture. I never would have put those two things together. That’s just horrifying. And it’s so interesting to have that clarified for me. So, thank you for that. Well, I am disappointed that the hour has flown! Lē and Melanie, thank you both so much for being here. I’m wondering if we could close out the episode with any final thoughts that you’d like to leave with listeners.

LIW: Well, I’ll jump in and say that I think the thing that we really need to be thinking about here is the gender binary, how it’s totally at the root of this problem, how it’s a false construct. You think it’s everything, but it has no basis in fact, it has no basis in even physiology. And when we start looking at what all of this means in terms of the gender binary and upholding the gender binary, because that is the foundation of patriarchy. You can’t have patriarchy without a gender binary. Then it starts getting a little clearer what we need to be approaching. Maybe we should be approaching what underlies all these problems instead of looking at the problems themselves. Maybe we should be approaching the gender binary and the illusion that that is. That’s just something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

AA: Wonderful. Thanks, Lē. How about you, Melanie?

MSM: Yeah. Like I said, I feel like I could talk about this and rage about this for a couple more hours. I come back to what I said earlier about Letha and Nancy’s idea that God has created us uniquely and that we’re fearfully and wonderfully made, and that patriarchy takes away the opportunity for anybody, including men, but anybody else to become who God created them to be. And I think Lē is absolutely right that as long as we see this gender binary, we don’t allow people to be the unique people that they’re called to be or created to be. And that has been such an empowering idea for me, and I hope it is for other people as well. That we are all uniquely made, and we need the liberation to live into that uniqueness rather than being who somebody tells us we should be. And I think that’s what the patriarchy does. It tells us who we should be rather than who God created us to be.

AA: Beautiful. Well, thank you again so much, Lē Isaac Weaver and Melanie Springer Mock. Again, I’ll point listeners to Christian Feminism Today. The website is great and you can just dive in and see all of the wonderful work you’re doing. I’m so grateful for your work and it’s so wonderful to meet you. Thank you so much for being with us today.

LIW: Thank you.

MSM: Thank you very much.

LIW: Yeah, we enjoyed it. Thanks for your work, too. Keep rockin’!

That’s a dangerous situation when you dehumanize everyone who’s not adhering to your beliefs.

But that’s where we are.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!