“there’s a lot of history about this relationship between women and adornment”

Amy is joined by historian Jill Burke to discuss her book, How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity, exploring cosmetics and beauty expectations of 15th-century Europe, and how the beauty industry continues to shape our culture today.

Our Guest

Jill Burke

Jill Burke is a professor of Renaissance Visual and Material Cultures at the University of Edinburgh, a historian of the body and its visual representation, focusing on Italy and Europe from 1400-1700. She is currently the lead investigator of the Royal Society funded project ‘Renaissance Goo,’ working with soft-matter scientists to remake Renaissance cosmetic and skincare recipes. She talks regularly about Renaissance bodies on television, radio and podcasts, and she discusses the history of art and beauty on “Jill Burke’s Blog.” She lives in Edinburgh.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: A few years ago, historian Jill Burke stumbled upon a book from Venice, which contained incredibly detailed descriptions of beauty standards from the year 1562. She says she scanned the text open-mouthed, thinking, did women in the Renaissance really worry about post-baby stretch marks, graying hair, being overweight? About having fat arms, saggy boobs, noses that were too big, bad breath, smelly feet, or unsightly dribbling in their sleep? This book, The Ornaments of Ladies by Giovanni Marinello, included more than 1,400 recipes for the beautification of the face, hair, and body. It is organized body part by body part, describing what women should do to correct their many flaws in order to achieve the ideal.

Burke writes, “Women’s bodies are presented as forever unfinished projects to be constantly improved and worked upon in a way that feels eerily familiar. Marinello’s helpful tips double up as a kind of self-dissatisfaction machine.” This is the opening passage of Professor Jill Burke’s new book How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity. And this was one of the most entertaining, enjoyable, and relatable books I have read in a long time. I’m so excited to have this conversation, to talk about it with Professor Burke here today! Thank you so much for joining us.

Jill Burke: It’s so lovely to talk to you, thank you so much.

AA: We usually start each episode with a professional bio of the guest, so I’ll read your professional bio and then you can introduce yourself more personally after that. Jill Burke is a historian of the body and its visual representation, focusing on Italy and Europe between the years 1400 and 1700. She served as the principal investigator of a Royal Society funded project Renaissance Goo, working with a soft matter scientist to remake Renaissance cosmetic and skincare recipes. The Renaissance Goo project is part of Jill’s wider investigation into how people in the Renaissance tried to look good, how they sought to change their bodies, faces, and hairstyles to meet beauty ideals. Jill’s new book, How to Be a Renaissance Woman, delves into the pressures that Renaissance women felt to look a certain way, and also how they subverted beauty ideals and used them to their own ends. As I said, that’s the book we’ll be discussing today, and I’m super excited. But first, please introduce us to yourself, where you’re from and what has led you to do the work that you do.

JB: Well, I’m a historian. I’m originally from England, but I’m based in Scotland at the University of Edinburgh, and I have been working in this field for a long time, for 20 years now. I work as an art historian and a historian, and I came onto this subject for many different reasons, sometimes I think there are always things bubbling along in your head and you’re not even aware why you get interested in these subjects, but it was partly because I was working on writing a book on the Italian Renaissance Nudes, on the images of the naked body. And I was interested in how these images affected the way that people understood their own bodies and looked at other people’s bodies, and I thought that would be an interesting project. What I didn’t expect to find was so much material on this. I was really surprised when I found Marinello, this book that you’ve been talking about. When I actually started properly reading it, I thought, “My word!” All of this pressure to look a certain way that, I mean, I kind of felt that was a modern thing. Obviously in the 20th century we know about magazines and things, and now there’s Instagram and the internet and all this stuff. But then finding that women were under very similar pressures, slightly different beauty ideals, but very similar pressures in the 16th century, was incredible.

And it was something that I thought I’m really going to have to follow up on. As a university teacher, you normally teach students between 18 and 22, and most of my students in history of art were young women. And especially over lockdown, you can see how much their appearance could mean to them and how this can be both a positive thing, sometimes people like to play with hair and makeup, they like to play with their appearance and that’s great. This is not a book that condemns this at all. But there’s also pressure that people feel, and I really wanted to give people a history of that feeling and to show them that this is to do with society, it’s not to do with any individual problem. So that was the motivation. I want to make people feel better about their bodies and about their anxieties about their bodies and their faces, how they look, and to say that other women have been dealing with this for a very long time.

AA: That’s how I felt. That’s part of the reason that I loved the book so much. It was so interesting and so engagingly written. It was very funny in a lot of places, too. I loved that. But also having historical context always gives you a bigger perspective and puts your own, like you said, the kind of private pain or worries or insecurities that we have gives us perspective. And then you feel this bond with other women in different times and places, which is also a beautiful thing.

JB: Yeah, absolutely. And I started with this book, which was by a man named Giovanni Marinello, who was a male physician, but I did try very much in the book to find women’s stories and to highlight some of these amazing women that were around in the 16th and 17th centuries. Women who were not just brilliant writers or artists, but funny as well, and who had these friendships that sometimes aren’t highlighted in the past of women. Certainly when I taught students a course on Renaissance women, they thought it’s going to be all miserable, all suffering under the patriarchy. And there is that, absolutely, but there’s also these spirited women who push against these rules and do so sometimes very successfully.

AA: Love it. Well, shall we jump into the book? I have so many questions for you.

JB: Yes.

AA: We mentioned the time and place a little bit, but let’s talk about that to set the stage. If you can tell us what time period and geographical location that you talk about over the course of the book, because it’s not all focused on Marinello’s book.

JB: Yeah, mainly the focus is on Italy. I sometimes bring in some other places, but it’s mainly Italy. It’s the Italy of Michelangelo, it’s the Italy of Botticelli. Maybe as we go further it’s Artemisia Gentileschi, Caravaggio, so it’s Italy from around 1450 to around 1650, and that’s where the bulk of my examples come from. And this is a time period where a lot happens. People might be familiar with the idea or the term the Italian Renaissance, and this is a point when visual culture, when painting, sculpture and prints are changing very rapidly, becoming much more realistic, much more interested in representing nature. Science is changing, you get the first books with illustrations, so the first anatomical textbooks, for example, with illustrations. And of course, also a lot of global expansion from Europe. This is a time when European explorers are going to other places, notably Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas, and exploring but also subjugating the people who they’re coming across.

AA: What were some changes that were happening in the Renaissance specifically regarding how women were represented in all of those art forms?

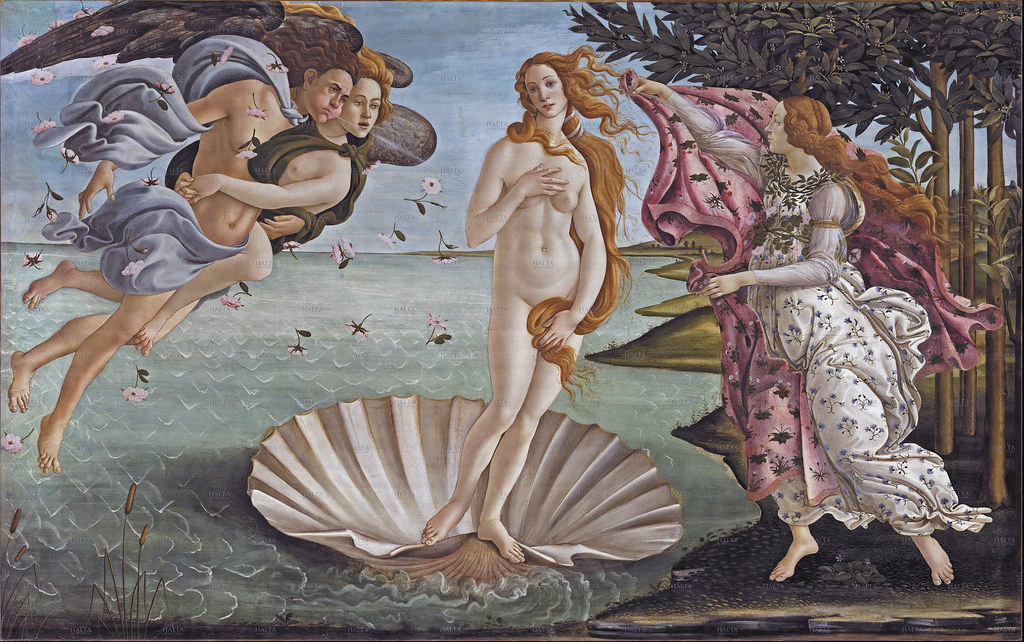

JB: Before about 1500, you get a handful of images of nude women, and they tend to show women with what we’d now call a pear shape, so very large hips and much more slim shoulders. But what happens in the 15th century in Italy is that people start to rediscover sculpture from classical antiquity, so that’s ancient Greek and ancient Roman sculpture. And this kind of sculpture often is very interested in the naked form, so they don’t have the same relationship to their naked body as they do in post-Christian cultures and Christian cultures, we’re talking about classical antiquity. And this includes some sculptures of naked women, generally the naked goddess Venus. And so people are very interested in this and people start to adopt this kind of representation of the naked body into their own art. So again, if you think of Botticelli, if you can bring to mind any Botticelli images, you might be thinking of the Birth of Venus rising from the waves on a big shell. And this is one of the first completely naked representations of the classical goddess in Europe in post-classical times. And Botticelli was working on that painting particularly in the 1470s or early 1480s. From that point to about 1530, you start to see these images proliferate, so more and more images of naked women. That’s one of the things that makes people think about bodies differently.

And the other thing that happens is, there’s lots of things that happen, but the other thing that happens is prints, so these images can get reproduced, and the printed book. So printing comes into being, and you start to get printed books from about the 1480s onwards that deal specifically with beauty tips and health tips. It’s like the internet, one of the first things that came out were how-to and advice and this kind of thing, and we get that as well. How-to books are still very popular now and they’re very popular in the late 15th and 16th centuries as well. But obviously they just didn’t exist in those numbers before. So there’s a lot of different kinds of changes at this time.

AA: Well, let’s talk about some of those beauty tips, and specifically maybe we’ll start with cosmetics. And I know that your specialty is goo, so can you talk about some of the goos that women used?

JB: Yeah. I’m working with a soft matter scientist, a physicist called Wilson Boone, and we have a project called the Renaissance Goo Project where we recreate some of these lotions and potions that people used to make. And soft matter is very interested in how, for example, moisturizer might feel in your skin, whether it might spread across your skin, whether it might sit, sink in, this kind of thing. That’s to do with the molecular structures that Wilson knows more about than I do, that are actually really important, they’re really central to how we feel a moisturizer works or not. We’re interested in whether Renaissance women knew about this and whether Renaissance makeup could teach us anything. And one of the things that’s really interesting is, for example, in the book there’s a recipe for a moisturizer that is actually an anti-wrinkle cream that has tallow, which is sheep fat, egg whites, and some tree gum, so some scented material, and a little bit of water. And when I first saw this recipe, I thought, “Oh, that sounds really unpromising.” Because if you’ve ever gone anywhere near sheep fat you’ll know it’s quite smelly, but we tried it anyway. And actually it works amazingly well and it feels like a moisturizer. So they knew how to make an emulsion that creates this light texture that we get in moisturizers. It’s not greasy like a balm or anything. And they knew how to cover that sheep smell with particular tree gums. They used incense, frankincense and mastic, both of which are gums that come from a tree.

So actually what we found is this massive amount of sophistication with these goos. We always assume that Renaissance makeup is terrible, it’s made of awful ingredients and they’re all poisonous. And some of them absolutely are. But at the same time, there’s an awful lot of knowledge in there. There’s all things that we might use. There’s anti-wrinkle cream, there’s things for acne, like face tonics. In terms of color cosmetics they have lipstick, they have eyebrow color, they have hair dye. They don’t tend to focus on the eyes as much as we do, so there’s maybe not so much mascara or eye shadow, but everything else is really similar. Lipstick, blusher, all this kind of stuff is present in these books.

AA: Amazing. It’s so interesting. And you got these recipes, as we said, the Marinello book has 1,400 recipes, right? Were there other sources that you got, like, “here’s what we used and here’s how we made it”?

JB: Yeah. The best printed beauty book is from the 1520s, which I didn’t know about. That took a bit of research to dig up. So that preceded Marinello, and this is aimed at much poorer women. The Marinello’s quite a fancy, large book that would have been quite expensive. But there are these little pamphlets, which are maybe 20 pages, which contain makeup recipes. And there are also manuscripts, so there was a woman called Caterina Sforza, who’s the Countess of Imola, a place in Northern Italy, and she wrote down cosmetic recipes. So they exist in really large numbers. It’s not just Marinello, they exist all over Europe and beyond. I have a student who was looking at Chinese cosmetic recipes from the same period, for example. It’s not just Europe. The problem with some of these recipes is that they’re not written down. I bet they exist from everywhere, but I think it’s a really important oral tradition amongst women, particularly where this kind of stuff is difficult to capture now.

AA: Yeah. Maybe once they started manufacturing them in factories that died out.

JB: Yeah. I think the 19th century is a time when manufacturing this kind of stuff starts to really take over, but up until the 18th century you get quite a lot of these books, in English as well, which tell women how to make certain types of cosmetics and what they call waters, like perfume and things like that. But then the shift, I think, happens in the 19th century when you start to get all these big cosmetic companies starting.

AA: That makes sense. Another aspect of beauty was body shape, and this was really interesting to me too. You write that “In the Renaissance, as now, people would go to elaborate lengths to alter the shape of their bodies to meet the ideal.” Yes. Then as now, for sure. So what was the ideal body shape and how did people achieve it? Maybe you can talk about a few different parts of the body that people tried to alter.

JB: The ideal body shape overall for women was probably fleshier than the ideal today. It was hard for Renaissance women to be plump, and most women were working all the time and doing hard physical work. So this ideal, this kind of plump, soft-skinned ideal is probably something that only the richer women really could attain. But it was important not to be too plump because they didn’t want you to be too fat either. So there’s the slightly difficult balancing acts that you have to do in the Renaissance just to fulfill these beauty ideals. And along with this kind of plumpness, so you had to have plump thighs and round cheeks, a little double chin was perfect. You also have to have very small breasts, for example. And so breast binding, a lot of recipes recommend that mothers stop the breasts of their daughters growing too much. There’s also a lot of discussion of how to keep your body in proportion. So if you want to make something smaller, you have to bind it up in the bandage and put cumin on it and various rubs.

And again, elements of this are reminiscent of things that people say now, like being wrapped in cling film or Saran wrap or, you know, people recommend crazy things. But one of the nice things about the way they discussed body shape and body weight in the Renaissance is that they thought about it holistically. They thought that if you were melancholic, for example, that you’d lose weight. So one of the ways to gain weight was to listen to music and be happy in the evening, that’s one of the things they recommend. And although it sounds crazy to us, in a way it does recognize something that is true. That all the stuff is to do with the whole body, the mind and the body together. This is why losing weight or changing weight is so tremendously hard, is that it involves the whole body and the mind and everything, rather than just this idea of the body as almost machine-like. So that’s kind of good. And there’s a recipe in the book actually for gaining weight, which is these lovely little nut balls mixed with honey, which I really would recommend. They’re really good.

AA: They sound good.

JB: Yeah, they’re really tasty.

AA: Okay. Could we talk about three specific things? Breast bags, nose jobs, and labiaplasty. Those were really interesting to me too.

JB: Right, so let’s start with breast bags! This has to do with a discovery that was recently made actually by this wonderful archaeologist called Beatrix Nutz and her team that were working in Austria. They used to think that bras originated in the 19th century, but in the walls of this castle, they found a lot of 15th-century underwear including bras. Amazingly they found some 15th-century bras, and so it looks like they were much earlier than people thought. And again, they were to keep the breasts kind of small, so they fitted in the dresses at the time. And this flattening of the chest also happened with very stiff bodices that they used to have to kind of contain the body. So the breast bags are something that’s actually new to scholarship. And the nose jobs! So, nose reconstruction surgery started in the 15th century. This is something that is unbelievable.

AA: It’s crazy! I know, I could not believe it.

JB: But it is actually true. But it was so painful to do, I don’t think it was done very much. But the technique was written down in the 16th century, and there’s an incredible woodcut and that incredible illustration in an Italian book of the 16th century by a surgeon called Italia Cozzi, which shows how they did it. And what they did was take skin from the lower part – it’s really awful – the lower part of the arm, which was held up by an apparatus, and they would sew it to the place where the nose was. And you’d have to keep your arm raised so the skin was still attached to the arm and attached to the face at the same time. And they’d shape this nose until the nose actually had its own blood supply on the face. And it did work, apparently. There are records of this having worked, but yeah, it’s unbelievable.

AA: Unbelievable. I forgot that detail. Holy cow. Oh my gosh.

JB: Well, I can’t imagine how awful it must have been to do that, but that was what they did. It’s amazing that they tried it and this worked. An incredible thing. But one of the reasons why they had to have it was that chopping off someone’s nose was a shaming ritual. I mean, it’s really terrible. There’s an account of this woman called Susannah who had her nose chopped off because she resisted the sexual attacks of Swiss soldiers, and she was one of the people who had this operation successfully, by all accounts.

AA: Oh my goodness. Well, that makes sense. Actually, listening to you now, I had forgotten some of the details from the book that you just described. But I was thinking that you would have to be really, really unhappy with your nose to undergo something so painful, but that makes sense. I mean, if you’ve been disfigured, then that would be something–

JB: Yeah, it was something that happened to women. If you were adulterous, for example, it could be a punishment that you’d have handed down by the authorities. I mean, one of the things that is important to understand about the Renaissance, we think about all these beautiful paintings and things like that, but it was a violent time. Often for women it was a really dangerous time.

AA: Well, speaking of that, the last topic on this is labiaplasty. Tell us about that.

they were to keep the breasts kind of small, so they fitted in the dresses

JB: This is quite disturbing as well, actually, and it’s to do with how people understand that women should look. How women’s genitalia should look, particularly. It was quite difficult uncovering evidence about this, but certainly there’s a lot of evidence that points to women having their labia and clitoris removed or chopped off for aesthetic reasons by midwives. This would normally happen in the 16th century in Italy and France. And it’s really disturbing when you get to grips with this, but this is something that seemed to have happened sufficiently so that in medical dictionaries there’s a word called riadica, which refers to what happens when this operation goes wrong and there’s bleeding that cannot be stopped. So although there’s little trace of this that you can cover, it seems that there’s this ideal genitalia that women should have. One of the issues is that if they don’t have this ideal genitalia, they could be sexually promiscuous.

AA: Yeah. Well, I think that’s so important to highlight. We did a whole episode on female genital cutting last season, and I just think it’s so important to know that this happened in Europe also. It’s not just something that has been in one place, or people associate it inaccurately with a certain religion or a certain place. It’s happened in lots of different places.

JB: Yeah. I think it is important to realize that this is happening in Europe, this is something that’s recommended in Europe as well.

AA: And also, we talked about this on the FGC episode too, that it was women who were perpetuating it. These are patriarchal norms that undergird the practice, so it’s rooted in patriarchy, but it’s actually women who are doing it. And that happens in all kinds of patriarchal constructs.

JB: Because women are also affected by the patriarchal culture and vessels through which this operates. That’s why having this term “patriarchy” is so useful, because it’s not about women being against men, necessarily, it’s about this whole ideology being embodied in different people in different ways, often unconsciously. Because I’m sure that these women thought they would be helpful.

AA: For sure. Well, speaking of that, some of these patriarchal norms– and if it’s okay, I’ll read a little section of this next part of the book. You write, “Looking good was important for women in a world where the legal rights and earning power of men meant that influence was often gained through manipulation, where beauty could raise your social status, and where prospective husbands could scrutinize your body, hair, and face for signs of wifely obedience and fertility. Renaissance women cared about what they looked like. They had to.” Let’s talk about that a little bit. I didn’t have any prior knowledge, well, I guess it kind of reminded me of phrenology, like the belief that you could feel someone’s head and know something about their personality. Can you talk about that?

JB: Yeah. So in the Renaissance, they believed the body was made up of four different kinds of liquids, which they called humors. These still enter everyday language. Phlegm was one, and for example, the word phlegmatic comes from that idea. Blood was another, the word sanguine comes from blood, so if you’re a sanguine person you’d be dominated by blood and so on. Bile is another one. So all these terms we know in our language are related to both the substances in the body but also personality. And in the Renaissance, people believed that you could tell what was going on inside of the body by looking at the outside. So there’s a big fashion, and it is a little bit like phrenology which came later, there’s a big fashion for physiognomy in the Renaissance. So there were books that gave you kind of keys to reading people’s appearance. And so blonde women, for example, if you had very light blonde hair, you were thought to be stupid. This is something that has very old roots. Well, if you had darker blonde hair, this was good because you’re fertile and obedient. If you had dark hair, particularly dark curly hair, you were thought to be possibly disobedient, argumentative, and probably infertile.

There’s a whole book by a Spanish physician called Juan Huarte, and a part of the book is designed to tell men who they should marry so they’d get a good and clever child. And most of the men should marry the perfect woman with this lovely, slightly wavy, dark blonde hair, peaches and cream skin. So the ideal beauty because she’s more likely to be passive, more likely to be obedient, and more likely to have intelligent and beautiful children. So when you see these renaissance beauties by people like Titian, for example, or Raphael, they’re not just about appearance. It’s also about what these women are like and how they react to men in that, I suppose, like a passive way. So this is why people hated makeup so much, partly because they said you’re mis-selling the goods, effectively. Because people with dark hair can bleach their hair to look golden and then you marry this person and you find out they’ve really got dark hair and they’re really argumentative.

AA: Haha. It’s crazy, but then you can understand that it would be incentivizing for women to be that ideal because you need a husband back then. You really do. You’ve got to be attached to a man.

JB: It’s really difficult. I mean, there are some women who stay single, and sometimes they manage. There are some who I talk about in the book, they always seem to me to be really impressive women because they’re making their way alone in the world. But in most Italian jurisdictions, and Italy was divided up into different states so it’s slightly different in different places. But in most places, all of Europe and all of the world probably at that point, women’s wages were much, much lower than men’s. So even just to look after yourself, it was really useful to have a husband. And of course, the more wealthy a husband you could have, which massively affects your future prospects at all levels of society, for women in the aristocracy as well, this was very important for dynastic reasons and for family performance. So it was important for everybody, for all women, particularly young women.

AA: Mm-hmm. The next topic that I wanted to bring up is still on this theme, and it’s about beauty manuals. And to me, these books seemed to be really overt examples of patriarchy because it seems like they were, if I’m remembering correctly, written by men prescribing practices for women. And written so that women can get husbands, right? Can you talk about these beauty manuals?

JB: Well, Giovanni Marinelli’s Gli Ornamenti, that you talked about at the beginning, is a good example. There’s a bit in there when he talks about body hair removal, and it’s right at the beginning of the book. And this is one of the reasons why I thought, “Oh my word, I have to work on this.” He addresses the reader all the time and he says, “Ladies, if you don’t remove your body hair and leave yourselves looking like a wild beast, you can’t blame your husband if he goes behind your back looking for another lady.” And you think, “My word, this is terrible! What is he saying to this woman?” So basically, it’s a woman’s fault if a man is adulterous. Because in our time we’d say, “oh, she’s let herself go,” you know. And so you think, oh, these poor women in the 16th century reading this and again, blaming themselves for the actions of men.

So yeah, in some ways, these are absolutely just repeating these patriarchal ideas. In another way though, there’s another side to the patriarchy which says that women shouldn’t wear makeup at all and that it’s tricking them. And Giovanni Marinelli’s daughter is Lucrezia Marinella, who really is a feminist and she says women should be able to do what they like. So there are also arguments that some of the very early feminists say, like Moderata Fonte, who say, what do men care? You just stop bothering us about what we look like. Stop bothering us with telling us how we should wear our hair. We should do whatever we like. And so there’s also this other side to these beauty recipes and these manuals, and with Moderata Fonte you just feel how fed up they are with being bossed around.

AA: I loved that section of the book because you really do outline that yes, here, this woman thought that it was oppressive to wear makeup, and it’s quite didactic. And I actually follow some Instagram accounts as I’m working through my own relationship with the beauty industry and with my body image and all that stuff, and I do notice that it can become very preachy on both sides. So then you outline the reasons why you shouldn’t have to alter your appearance and you’re just giving your money to this industry, and this is oppressive and men don’t have to do that. But then you point out that you can find men who scorn women for wearing makeup, and you really highlight both.

JB: What was interesting to me about finding those varied viewpoints is that I think that people do struggle with both these viewpoints today. Am I kind of giving into this idea of the patriarchy, but actually, should I feel guilty for wearing eyeliner? I mean, no. One of the things that I think is really important is that life isn’t a series of straight lines. And that things are sometimes one way or another, you know, but I don’t think we should say it’s wrong to wear makeup. I think we should say, yeah, I understand that this is a world where it’s complicated, where women’s insecurities get exploited for commercial reasons. Yes. But at the same time we can have some fun with cosmetics, and they are an arena sometimes for creativity and for making people feel better and for reconstructing yourself, you know, remaking yourself. Both of these things can exist simultaneously, both the good and the bad can exist simultaneously. And I think it’s one of the problems with the social media world we’re in sometimes, that these nuanced views get a little bit lost. And that’s a shame because both of them are right on different occasions. Laura Cereta isn’t wrong to say that staying up all night studying is much better for you, in a way, than thinking about makeup. But neither are the later women who say actually, beauty is very important to us. That’s alright as well.

AA: Yeah. Oh, I’m so grateful for that perspective. And having that conversation outlined from hundreds of years ago, it occurs to me now as I’m thinking about it how natural it is as human beings that across times and across cultures, humans like to paint themselves. They like to adorn themselves with things, right?

JB: Both men and women.

AA: Men and women. Yes, exactly. I was thinking it’s maybe more unusual that in the last couple hundred years in Europe and America that men don’t paint themselves in some way or wear more fancy clothing.

JB: Actually, you can see that shifting now.

AA: That’s true.

JB: When I was growing up, when I was a teenager, honestly the boyfriends I had then just didn’t care at all what they looked like. And I think that is really shifting now. There’s much more of a gym culture now for boys, there’s more pressure for them to look a certain way. I think there is a shift. But it’s whether this idea of adornment is connected with vanity, and that tends to be gendered female. And that in our culture goes right back down to antiquity, to classical, biblical times. So there’s a lot of history about this relationship between women and adornment, but yeah, you’re quite right that it shifts. And we’ve even seen the shift in the last 20-30 years.

AA: Yeah. Well, fascinating stuff. Here’s another topic, and I’ll read it as a quote again. You write, “The full length mirror was an archetypal Renaissance innovation, I would argue, just as representative of the period as the printing press, the atlas, or the handgun.” I read that and thought, “Whoa, crazy!” First of all, I didn’t know the full length mirror was an invention of that time, and then to equate it with such world-changing inventions, tell us about that.

JB: It’s very difficult for us to imagine not ever being able to look in a full length mirror. I don’t know, sometimes it’s very annoying if you’re in a hotel room and you don’t have a full length mirror, you have to stand on a chair trying to see, but at least we’ll have a large flat mirror. Before the late 15th century, the most common mirrors were small and round. So they were convex, which means they stick outwards. And the kind of reflection you get on that is a distorted reflection, so anything that’s at the front of your face like your nose kind of grows in size and anything that is further back recedes, so you don’t really see what you look like. There’s changes in technology in glassmaking in the 15th century in both Germany and Italy, which means they started to be able to develop big sheets of flat glass. You get the first full length mirrors in the late 15th century and they start to be much more common in the 16th century. So in this period people can see their bodies for the first time accurately in mirrors. And there’s all these paintings that start in the 16th century of naked women next to full length mirrors. So I think that there’s a shift in the Renaissance to inwardness, to inward thought, to a new idea of individuality. And you see this all over the place. You see this in, say, Shakespeare plays and poetry, as well as in paintings and diaries and things like that. And I can’t help but think the full length mirror played a massive role in this idea. And also in self-judgment, because you can actually see yourself as if someone else is looking at you for the first time. So I think this is a massive, massive shift and it is absolutely one that people don’t know about. People don’t think about it, but that did happen at this time.

AA: Yeah, I’d never thought about it. I was going to bring this up a little bit earlier when we were talking about the proliferation of the female nude, so I’ll just ask you now about the male gaze in art, like that famous quote, “men look at women, women watch themselves being looked at.” For women to then see more often, I guess common women probably weren’t seeing these great works of art very often, if at all. But maybe, I mean you said they’re being printed.

you can actually see yourself as if someone else is looking at you for the first time

JB: Yeah, like on the facade, people see art in things like festivals and they’re painted on facades of palaces and in churches. I mean, maybe fewer nudes, but still some nudes in churches. So women would have seen some of these developments. And the male gaze, it’s really interesting because the male gaze is a very powerful concept and it’s one that I think most women can identify with having felt scrutinized by somebody. And certainly when you look at Renaissance marriage and negotiations, particularly of the upper classes, they’d ask people to come around and view the girl in their underwear, in their undershirts. And this is just so typical of the male gaze. And you’re quite right about the mirror, as well. You get to almost take on this male gaze of your own. Women aren’t entirely passive though, there’s evidence that women are also looking at men and looking at other women with these desiring eyes. And men looking at men as well. There is an assumption in the literature that women also are attracted to women’s bodies. There’s no sense that you have to be what we’d now call a lesbian to be attracted to other women, it’s just something that people assume would happen, which is quite interesting. So there’s maybe a bit more of a proliferation of gazes, I mean obviously women are the main target for this, but you do get women talking about men in very desiring ways in this period as well. So it’s actually a little bit more balanced than just women seeing themselves being looked at, because women can do the looking. And at that point we’re doing the looking as well.

AA: Mm hmm. Oh, that’s great to know that it wasn’t as bad as you think. The last topic I’d like to bring up is encapsulated in this quote from the book. “Renaissance beauty ideals were unyielding and deliberately exclusive.” So I wanted to ask you, we’ve talked about the patriarchy and the hierarchy of sex, but we haven’t yet talked very much about the hierarchies of class and race. How did beauty standards play into those hierarchies?

JB: There are very stringent ideas about skin texture and color in this period. A lot of these recipes are designed to make skin whiter, to avoid the sun, for example. So a lot of women were working outside, a lot of women working in agriculture, and it would be very hard, you know, working with their hands at a time when you don’t have rubber gloves, you don’t have all these protective things. They were already excluded from these kinds of beauty ideals. And it’s also important to remember that Europe at this time, and Italy at this time, particularly Venice and some parts of southern Italy, were what we’d now call multicultural societies. There are a lot of people who are not European by descent, there are people from North Africa. There’s a wonderful image of a North African woman with two courtesans in the gallery here at Edinburgh, and she’s got facial tattoos which locate her as a woman who was originally from the Amazigh community.

And then there’s an awful lot, a big fashion for having slaves or servants who were of Sub-Saharan African descent, and so you start to get slaves from Sub-Saharan Africa coming into Italy from the mid 15th century. It’s about this time when you start to get images like, well a bit later, the early 16th century, like Titian’s Laura Dianti, which is a portrait of the mistress of the Duke of Ferrara. And she’s shown with a Black servant or slave, and this kind of sparks a whole fashion for these fancy aristocratic ladies to show off their white skin against these foils of Black servants who tend to be obviously of lower social hierarchy.

So, it’s interesting how the idea of beauty feeds into these ideas of social hierarchy, racial hierarchy, and class hierarchy, and excludes some people from it as well because there’s an emphasis on whiteness. And what I want you to get from the book is not that this was a completely white society, it just wasn’t. I know that people think that if you have Black people in Shakespeare dramas it seems anachronistic, but it’s not. This is what we know now about these societies. There are places like Livorno in Italy where one in ten of the population in Livorno was not white. So there are certain areas, particularly port cities, where these people come in as slaves. They’re often freed later on, but they stay and they have families as well. And this isn’t anachronistic and it is part of who gets included in these beauty manuals and who gets excluded.

AA: Mm-hmm. And you can see roots of white-centric beauty standards that persist to this day, right?

JB: I mean, it’s interesting. These manuals completely ignore the idea that you might not be white. They just don’t even think about it. And that’s a real issue with some of these beauty standards. It’s not even that they’re being deliberately racist, it’s just that they’re not incorporating a whole swathe of humanity in their discussions at all. And certainly this has changed recently. But it used to, certainly within living memory, this used to be the case. So again, you see these roots in the 16th century and it’s exactly the same time when you start to get the beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade, for example.

AA: Yeah. And as you said, it’s just tragic and repulsive to hear it, but that white women were kind of using these people as a foil, like you said, to show off their white skin. As there were more people in the community with darker skin, they wanted to emphasize, like, “Look at me, I have white skin which means I’m rich. I can afford to have enslaved people.” Just like you said with body type, like I want to show that I can afford to just sit around so I’m fleshier. So the way that beauty standards demonstrate kind of this aristocratic–

JB: Yeah, it’s a way of showing that you’re a member of the elite and that you can afford the time and the effort to have this white skin and to make your white skin contrast with another person who’s not white. Isabella d’Este, a machinist in Manchuria in the early 16th century, asked for her agent in Venice to buy a Black slave girl who’s as Black as possible. It’s part of Renaissance culture, it’s part of the European heritage that we also need to understand and appreciate how we got from there to here. It’s part of the culture that maybe when people think about the Renaissance they don’t know what we think about.

AA: Yeah, for sure. That was new to me. Well, that brings us to the end of the conversation, Jill. Was there anything else that you wanted to add as we wrap up?

JB: Thank you for reading the book so closely and for asking such interesting questions. When you start to look at beauty, it goes into every aspect of life and every life stage. You did ask about influences and things, and my interest in this topic has been since I was a mother and I wasn’t able to engage with these questions, with what I looked like, as much as I did previously. Motherhood changes your body an awful lot in ways that often aren’t talked about. I did have a section of the book that I actually had to take out about dealing with stretch marks, because this is a big thing that women were really worried about in the Renaissance, was stretch marks on the belly. And there’s a beautiful image of a postpartum woman that I talk about on my blog actually, but it didn’t make it into the book. But certainly I think that’s been one of the reasons why I thought about this. And sometimes when you have little children just getting out of the house without having stuff all over your clothes is a triumph.

AA: A victory for sure.

These manuals completely ignore the idea that you might not be white

JB: So I think that’s what made me think about this and how unfair some of these beauty standards can be for women at different life stages and for women of different backgrounds. So, that was how I came into this and into writing the book in the first place.

AA: Wonderful. Well, I’ve definitely recommended it to all three of my daughters and we’re reading it as a book club soon, so I’m spreading the word to as many people as possible.

JB: Oh, thank you.

AA: It’s just wonderful. Jill Burke, thank you so much for being here. Again, the title of the book is How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity. I can’t recommend it highly enough, and thank you for a lovely conversation, Jill.

JB: Thank you so much.

we think about all these beautiful paintings and things like that…

but it was a violent time. Often for women it was a really dangerous time.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!