“Forget about hearts and minds here, let’s talk about property values”

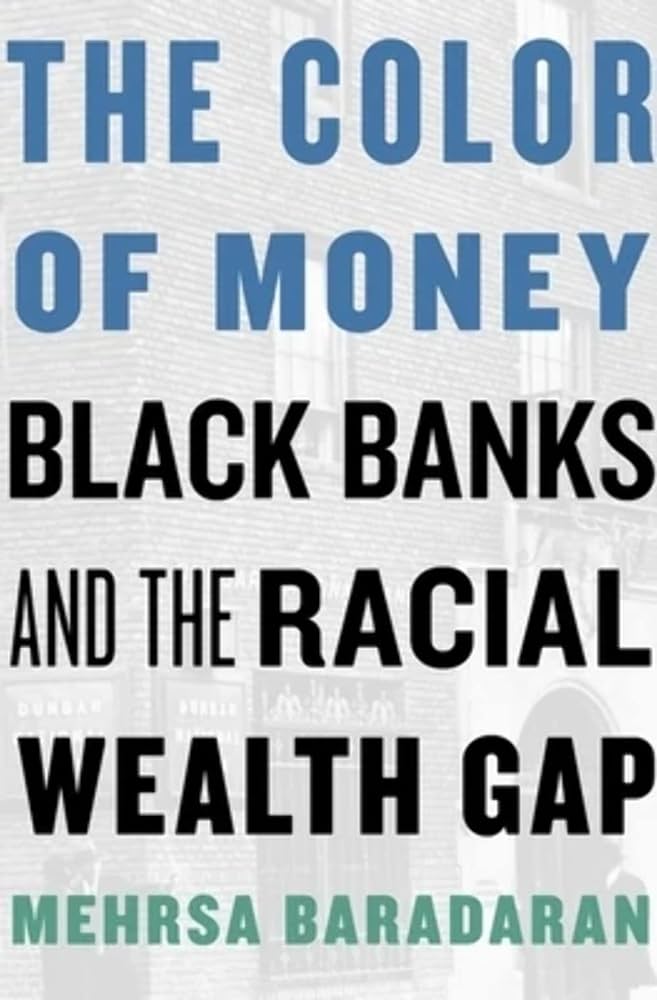

Amy is joined by philosopher and author Mehrsa Baradaran to discuss her latest book, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, and explore the history of Black banking, intersections of race, gender, and economics, as well as how we can take control of our economic future to create a more equitable world for all.

Our Guest

Mehrsa Baradaran

Mehrsa Baradaran is a professor of law at UC Irvine Law School. She writes about banking law, financial inclusion, inequality, and the racial wealth gap. Her scholarship includes the books How The Other Half Banks and the award-winning The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, both published by the Harvard University Press. Baradaran and her books have received significant national and international media coverage and have been featured in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, American Banker, The Wall Street Journal, and Financial Times. On NPR’s Marketplace, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, and PBS’s NewsHour, and as part of TEDx at the University of Georgia. She has advised US senators and congressmen on policy, testified before the US Congress, and spoken at national and international forums like the US Treasury and the World Bank.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Today we’ll begin with a few quotes, so just let them sink in. First, from W.E.B Du Bois: “To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.”

Second, from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “All too often when there is mass unemployment in the Black community, it’s referred to as a social problem. And when there is mass unemployment in the white community, it’s referred to as a depression. But there is no basic difference. The fact is that the Negro faces a literal depression all over the United States.”

And a third quote, a saying that goes, “When Wall Street catches a cold, Harlem gets pneumonia.”

Many of us have heard about the racial wealth gap. Maybe we’re even familiar with statistics such as the fact that during the 2008 financial crisis, almost half of the wealth of the Black community was lost. But how much do we know about the root causes of the racial wealth gap or what the real implications are? To learn about this issue I read The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, and I am so excited to welcome its author, Mehrsa Baradaran. Welcome, Mehrsa, thanks for being with us.

Mehrsa Baradaran: Thank you so much for having me.

AA: Your book made such an impact on me. I was so really blown away and read it really slowly. There’s quite a lot of data and I really appreciated that, I learned so much from the book. It’s full of data and also full of real stories that make an emotional and psychological impact as well. I can’t recommend it highly enough to listeners. What we usually do on the podcast is that I’ll introduce you first professionally and then we’ll have you introduce yourself personally right after that.

Mehrsa Baradaran is a professor of law at UC Irvine Law School. She writes about banking law, financial inclusion, inequality, and the racial wealth gap. Her scholarship includes the books How The Other Half Banks and the award-winning The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, both published by the Harvard University Press. Baradaran and her books have received significant national and international media coverage and have been featured in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, American Banker, The Wall Street Journal, and Financial Times. On NPR’s Marketplace, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, and PBS’s NewsHour, and as part of TEDx at the University of Georgia. She has advised US senators and congressmen on policy, testified before the US Congress, and spoken at national and international forums like the US Treasury and the World Bank.

And like I said, we’ll be discussing The Color of Money today. Mehrsa, again, thanks so much for being here. I wonder if you can now start us off by telling us about you, where you’re from, and the influences and factors that have gone into the work that you do today.

MB: Yes. Thank you. I was born in Iran, I immigrated to America when I was nine. We joined the LDS Church at that point and half of us, my mom and my sisters and I would go, but the first time I had been to Utah was my first day at BYU. And I had been in the Church for a while and left probably 10 years ago. But I kind of have an on and off, I go occasionally and not. I taught at BYU for a couple years and then I taught at UGA and I’m now at UCI. I’ve written mostly about my specialties in banking law, and I have wed my passions with my skills. My passions have been in justice and equality and also understanding what went wrong and when it went wrong and how it went wrong. So when I write these books, it’s usually– I got tenure a decade ago and I don’t have to be writing these books. I could be writing these journal articles that nobody would read. But the books have been my own personal, sort of, let me take five or six years and try to understand something. And The Color of Money was that long. For How The Other Half Banks I think I had more of a sense of where it was going to go. The Color of Money started as a whole different book and ended up as that book.

And I have another book coming out in May that is also kind of a personal journey through the materials to see what comes out. The Color of Money started to be about these weird outside banks, immigrant banks, there was all this stuff in the literature like this Italian Bank and German Bank. So I was going to do this book about these immigrant banks and what that showed about money and finance. And as I started digging around in that research, that led me to focus on Black-owned banks because there was something there. And then it became a book really about the racial wealth gap. And not just that, but the myths that we tell about the market, about race, about how economics works. So that’s essentially what the book covers. And each book kind of leads to the next book.

The third book that is coming out in May goes more into really tackling the ideology that took hold in the late 1960s and 1970s which justified these inequalities, where the civil rights laws had come out in the ‘60s saying you can’t do discrimination, you can’t do Jim Crow, you can’t do segregation. And after World War II, it’s not okay to say some races are inferior. It was never okay, but the world and that consciousness changed. But you have to justify, if you’re in power, the fact that Black people live in the ghetto and they didn’t have as many jobs. You can’t use these old laws and ideologies, so these ideologies adapt.

And the ideology that adapted and came out of that moment was this free market slash “it’s the market that did this. It’s not the laws, it’s not a century of slavery and Jim Crow, it is supply and demand curves and just the invisible hand.” As this book shows, I say that either US market wasn’t capitalist, because this is not capitalism. What you see in this book and what anyone experiences in or outside of those redlined areas is not capitalism, and I can go into that later as to why. Or, capitalism isn’t what we think it is, that it doesn’t discriminate. I don’t think either of those things are true. I just think capitalism is a great theory, a great way of running an economic pricing regime and all of that stuff. It’s just not this economy that the US has had. You cannot describe a system as capitalist that doesn’t allow certain people to have certain jobs for many, many years and has so much government intervention in the process of banking, which is what I study.

I got into this by way of introduction, I left law school, and I went right to work at Wall Street at one of these big law firms. And our clients were banks. I was there from 2005 until 2010 during the financial crisis. And I saw, look, we were advising all these banks and then all of a sudden the Fed is printing money to put into these banks. And it was all legal, we were the ones creating the laws, we were the ones that wrote the laws afterwards. It was all perfectly above board legally, but it was unfair as people were losing their jobs. And that ideology broke down for me at that moment. This is not capitalism at all, because they have a money printer and those guys don’t.

And we’re blaming these homeowners for losing their homes. Where the banks were just as dumb. I mean, we were blaming them like, “these guys are dumb, they over-leveraged.” Those banks didn’t know what they were doing. They were sophisticated, they screwed up, but they had connections. And there was this whole ideological framework that needed to be defended, and the Fed came in and defended it. And it wasn’t just the Fed, it was the presidency, both parties, it started during Bush and continued through Obama. It’s not Republican or Democrat. It is an ideology, and I call it neoliberalism in my third book. I go into it a little bit in chapter six of this book. It starts around the Nixon era and it’s this idea that the market decides things, like this outside god-like force that cannot be meddled with or else bad things will happen.

AA: Before we start our conversation, Mehrsa, I just want to have one little tangent because I know that you’ve also done a lot of work on patriarchal systems. And because this podcast is about patriarchy and the intersections of other oppressive systems, I’d love it if you could talk a little bit about the work that you’ve done specifically on patriarchy as well, before we dive into The Color of Money.

MB: Yeah. Actually, I haven’t written a book about it, but it is the life I’ve lived. You cannot be a woman in finance, you can’t be a woman at all, you can’t have done anything in any system like Wall Street or academia or places I’ve been without rubbing elbows with patriarchy on the daily. You can’t be a mother of three children or a member of the Church without dealing with that. But what’s fascinating is that as I’ve gone into my money research finding, again, my personal battles merging with my academic battles. And my academic battles were always with these myths that we tell about the poor.

And if I could just boil it down to one thing, it’s that you are wrong about why people are poor. And let me take seven years and read all the documents and show you. And what this last book did, it was a very, very painful book to write. I literally just searched for like, when did it go wrong? Because if you go back into money’s history, what is money? Money is this agreed upon value and it’s something that has changed over time. It was gold coins, it was gold bars, paper, now it’s just digital. And you look at Bitcoin, which came out my first year at BYU, the Whitepaper came out and it was worth nothing and now it’s worth $46k. It’s not useful for anything, it’s just that you had a bunch of people agree that that is valuable. And as long as you agree that that’s valuable, it is valuable. That’s how the US dollar works. That’s how any economy works. We all agree that we’re going to take that money, and if you can take it, then it’s valuable.

And going back into the history of money and gold and realizing that the way that all those ideas about money needing to be scarce, like only the king can do it and it has to be backed by some military, that same moment was also the moment where you could sell a daughter into slavery to pay off your debt. And women were the first slaves, right? In any society before the slave trade began in the 1600s, when the Portuguese went to Africa and start trading slaves, and then 1450 is when colonization kicks off with South America. And well before that, you have the selling of daughters, and sons also but mostly daughters, for debt. If you look at the Old Testament or the New Testament, or any holy book whatsoever, you see evidence of this. In Leviticus there’s “sound the liberty bells,” like on the Liberty Bell it says Leviticus proclaimed freedom and it’s a debt jubilee. And it’s like, “tell the daughters to go back to their homes,” right? And Jesus! You cannot with debt enslave people in this system.

And after that, then you have continental takeovers for gold bars. I mean, if you just envision world history as these pirates from Spain and then these pirates from Great Britain. We’re not even talking about empires at this point, we’re talking about Francis Drake and Columbus and Pizarro, these mercenaries that go on commission from the crown, who say, “Go find gold, go get nutmeg in India.” And then they land here like “This is India.” They don’t have nutmeg, but they have gold. We’re going to slaughter and take the gold. And that crime begins centuries of war over this ideology of what is value. Instead of trading with the Native Americans here, who had these robust systems, this was not this desolate land, there was trade, there was civilization, there were philosophers that went to Europe at the time to try to explain their system of property. And instead of trading, instead of learning from them, they slaughtered them and took jewels. So that’s race.

And then they have to use a theory. The money comes first, and then the guys who murdered these people were like, “we did it because they were savages.” If you think about that word and who is saying it about whom, so race is used then. And then after that, 200 years later, they go to Africa and they really up race. Race becomes this imaginary construct to justify slaughter. And the moment of empire starts where you can say, “We will come, we will take over your land. We will take the women and their bodies. They are our property.” And the second women and people become property… For what? For money, empire, some symbol that is out there that no longer exists. Yet we still have these ideas about money built into our system.

And maybe we know some of this stuff. I think it is incredibly liberatory, though, when you really understand how deep it goes. I think it can feel very like, “Ah, this is awful!” But when you realize all of the wrong thinking that we have about value, it becomes very freeing. Because maybe now all of these thoughts that I had about how if I’m not working and making money I’m not valuable. Men are inherently more valuable in this economy because that’s how it was structured. It’s a male economy, and value is measured by how much you can make in this bullsh*t system of who are the highest paid people. Like the Sam Bankman-Frieds of the world, who are maybe good at math, but better at believing in their own bullsh*t for the most part. Anyway, I think there’s a lot of intersections, and depending on how deep you want to go, I think there’s a lot worth exploring.

AA: Oh yeah, for sure. Well, I can tell already that we could spend hours talking about all kinds of things, but thank you for that introduction. Amazing. I’m looking forward to your next book, for sure. But for now, let’s dive into the book itself, into more about the racial wealth gap. I was blown away even from the very first concept. One of the first things you talk about is that when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, and here I’ll quote the book, “the Black community in 1863 owned a total of 0.5%” – so half of 1% – “of the total wealth in the United States. This number is not surprising. Slaves were forbidden to own anything, and the few freed Blacks living in the North had few opportunities to accumulate wealth.”

So my question for you, Mehrsa, is it’s been more than 150 years since then, so how has it grown? What’s the percentage of wealth held by Black Americans now?

MB: It hasn’t changed. It’s 1%, something around that. And you can obviously come up with counter examples. What about Oprah? What about LeBron James and Jay-Z? Yes. But we’re talking about means, we’re talking combined. If you are, let’s say 14% of the population, why should you have less than 1% of the wealth? And then if you take that globally the number is way worse. And I want to be clear, it’s not like a white/Black thing. It is not that every white person is rich and every Black person is poor. And so that’s where race gets mixed up. But there has been a joining up of race and poverty and a criminalization of poverty that has also created this system of inequality. And so when people say systemic racism, that’s what they mean. Forget about hearts and minds here, let’s talk about property values, and the way school districts are funded, and where police show up, and what kinds of things are criminalized, things like that. I finished writing this before Trump had won.

AA: Oh, okay.

MB: I had to redo the end after I realized, because I was preparing for a Clinton presidency. That’s where it was going. So I was kind of writing my chapters to convince Left people that we still have this race problem. You guys think it’s over because we’ve got a Black president, and then Trump won and it did a lot of that for me. And unfortunately the book preceded Black Lives Matter and the conversations around this stuff. So now I go out there and people are like, “Oh yeah, we know about that.” And that’s great. That’s the silver lining. I think a lot of the things I felt in writing the book, like how am I going to convince people that this is important? And George Floyd did that in a second, and all of a sudden these conversations just bubbled up to the surface.

A lot of us who had specialized in this stuff had been writing, and it sucks to have your book become relevant because of something like that, but it is good that the conversation is there. And I think that a lot of those conversations need to be happening across the board, the way that race, gender, systems and ideologies that keep a privileged few in power and convince those that aren’t that it’s their fault. Or it’s something about them that makes them not as good, not as mathy, whatever it is. That ideology is like mental violence, the salts on the wound. And that’s what the book is filled with. There’s this George Bernard Shaw quote, I think he says basically that Americans have told Black people that they’re only good enough to be a shoe-shiner, and that just so happens that that’s the only job that they’ve let them do. So it’s this double thing where you’re only as good as that, but by law that’s the only job that we’re going to let you do.

And there are many examples of this in the Black community, like basketball or boxing. There’s all these ideas that Black people can’t do basketball, they’re just not smart enough. Boxing is a white man’s sport, and then you get one Black boxer in the 1910s and “okay, well boxing can be Black now, baseball can be Black.” And the way that the economics of that works is that when there’s a demand, when you can see it, the supply is always there. The talent is always there. When you can see a Black basketball player, you’re like, “let me go find more Black basketball players.” And now all you see is Black. Whereas it’s hard to imagine that 40 or 50 years ago you would’ve thought that basketball was a white thing. And it’s the same with venture capital. Like one percent of venture capital goes to Black people, two percent of venture capital goes to women. Two percent. And it’s because we don’t see it. Who are our heroes? You’ve got Steve Jobs, Sam Bankman-Fried, Elon Musk. It’s a specific type of genius that we recognize, and it’s very male-coded. Not male-coded but it’s logical, rational, masculine. And we all, I think, are half masculine, half feminine in different iterations. And I actually live in that world of logic, a little bit on the spectrum. I can understand that stuff. I don’t get mistaken for some absent-minded genius professor because of the body that I live in. But I see in my students when I look out on a class, because I am who I am, I can see that when you can be blind to race and gender, it’s amazing what happens. And I think most of us grow up in an educational system that has these ideas baked in about what is genius and who can perform and who is an entrepreneur.

there has been a joining up of race and poverty and a criminalization of poverty that has also created this system of inequality

So there are systemic issues and then there are the subconscious ways that we code certain things, and both of those things work together. And then on top of that is the ideologies. Ideologies are the hardest of all because these are things we don’t even question and don’t know to question because they just get passed down. I mean, any Mormon can understand this a little bit. And then when the fabric rends, you’re like, “Holy crap, what else have I missed?” And for me, going into the seams of the economy was that moment. The financial crisis was like the faith crisis like, “Oh my God, no one knows what they’re doing. This whole thing is like a Ponzi scheme or something!” And it’s not a conspiracy. There’s not five guys sitting in a room orchestrating it, it’s not even that smart. It’s a legacy of systems, but there are a lot of defenders of the status quo, and that’s the problem.

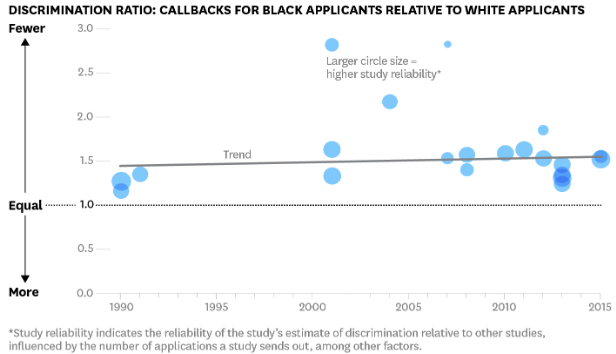

AA: Yeah. It’s such a great point that it is hearts and minds and it’s individual people and systems working together. What I was envisioning when you were talking, for example, we are a Silicon Valley family, and just picturing who gets money in Silicon Valley, it’s a system. It’s systemic. Our assumptions are created by the systems we see around us. But to your point, somebody made those systems up. And those are actual humans with their own biases who are sitting in the room listening to the pitch of the woman of color, you know what I mean?

MB: I’ve seen it! I’ve seen it in hiring. I’ve been in hiring for ten years, I see it in my students, I see it play out all the time. And if you’re not aware, you won’t see it. But if you’re aware, it’s enraging. I mean, look at Trump and Clinton. I mean, I cannot stand Clinton, I can’t stand Trump, but oh my gosh, did you see the way he treated her? It’s like patriarchy. When you see it, it’s everywhere. I’ve been in hiring committees where this woman of color is more qualified on paper by any objective measure, but then there’s something about her, like the vibe. And my colleagues are not racists, these are good people. And I will admit, early on as a teacher, I had to do a lot of work. I was a feminist in the crib, my mom’s a big feminist and my dad also. And so I was a liberal, like there is no difference in humans. All three of my sisters have careers, and I’m brown, I’m an immigrant. I have all of those stereotypes thrown at me and I found myself redoing those stereotypes.

AA: Oh yeah, we all do it.

MB: So when you catch yourself in it, you’re like, “but I’m a teacher!” And when a teacher does it it’s not acceptable. And I have worked a lot, I’ve been doing it for 15 years, but I had to force myself. It’s subtle. You cold call, like I call on a white guy and I’ll stay with him longer because I’m like, “let me push you on this.” Whereas with a girl, maybe I would leave her sooner.

AA: Really? Interesting.

MB: Yeah. That was the first thing I noticed at BYU. And I was like, “Wait, why did I just do that? Let me push her also.” Because you’re subtly sending these messages. Maybe I don’t want to scare you, you’re gonna pry. But you can do it with love. So it’s subtle, subtle things like that. And I blind grade, and I’ve seen it every year. Once you get the test, it’s a number, you don’t see the student. And every year my students of color get As. I had one at BYU where I knew it was a girl’s test because she kept saying, “I think…I feel…” so I started circling–

AA: In her essay? Like an essay test?

MB: Yeah, it’s an exam. It was like “I think, I think, I think.” And she had it right. So I gave her a good grade and then I brought her in and I was like, “I just want to show you this. If I were another teacher, I would have seen you equivocating.” But I read after that, “I feel, I think,” another teacher would not have given her an A. But I looked and I’m like, “You’re right, I know what you’re doing. You’re qualified.” And I saw my students do that, especially at BYU. It’s subtle.

AA: Yeah. And like you said, it’s in all of us. So all we can do is constantly try to interrogate and see and make the changes we can. Okay, I’d love for you to tell us, first of all, about the Freedman’s Bank. But honestly before we even do that, as a person who’s never been in law or in banking or anything, I think it might help to start with why banks are so important in wealth creation. Just a bit of the underpinnings of the philosophy and the function of banks in a system.

MB: If you read my book and get just that one thing, that’ll be enough. Both of my books go into it. Banks are incredibly complex, they’re fascinating. So is money. And the problem with banking is that it’s so complex and so hard to understand, and it’s so counterintuitive, that a lot of good people don’t understand it. And so they leave the theories to a lot of big macroeconomists, and those macroeconomists have really ideologically taken hold of the economy in a lot of ways. A bank is a money multiplier in its simplest form. You put your deposits in a bank and the bank doesn’t just keep those deposits, it lends them out and in doing so, it creates money. So when you give a bank, let’s say, a hundred thousand dollars of your money to hold, they’re going to lend out ninety or ninety-five percent of it probably. So you have a deposit slip that says one hundred thousand dollars. You have that money, that money’s in the economy, and then they lend out that ninety-five thousand to somebody else to buy a house. That person has ninety-five thousand dollars. You still have a hundred thousand dollars. That is new money. And then ad infinitum. Keep doing it. So that lending power is the power to create money.

Money is not like gold bars in the basement, it is credit. And banks have a license from the government to give credit using the state’s only source of money. And they don’t do it, you don’t even need cash. You don’t need deposits to lend, you don’t have to have the money at the vault because when you lend, now it’s all just a digital transaction. The bank just takes from the Federal Reserve and lends to the borrower. You can put in a little FICO score, sell it to the FHA within a minute. The FHA is like a federal housing agency, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, secondary markets. It’s just easy. If you qualify for a mortgage, you’re going to get a loan no matter how many deposits that bank has, and then that bank is going to get that six percent whatever interest rate you’re paying every month. This is why there’s been a lot of conspiracy centered around banking and banks. And there isn’t a conspiracy here. It really is like a magical institution. And the magic isn’t the bank, it’s the trust. Everyone trusts that I put my money in a bank and it’s going to stay there so they can lend it. That is what gives banks power. And the way that it used to be, that you’d have to have gold bars on the window, you’d have to be like JP Morgan to get that kind of trust. And now you have FDIC insurance. The federal government essentially insures all deposits so that you will trust a bank. So the state is basically the banker of last resort, and that gives banks power to create money. And this is all good so far, this is all how things should work.

The problem becomes that banks then use all of that state money, and that’s taxpayer money. We create the state, we vote and whatever democracy, da-da-da. And because of our trust in the state and that power that the state has, it gives it to banks, the problem is that banks and the state, it’s a collusion of sorts to enrich just a little minority. So they don’t have to give loans to low-income people anymore. They don’t give small business loans. They won’t give mortgage loans, hardly, if you’re a certain type of borrower, they will do big, big deals. Right now Wall Street banking is basically like a market of risk and arbitrage and complexity and it’s not productive. And so that’s basically the trajectory of banks.

In the olden days, when I talk about the Freedman’s Bank it is actually going back to that, a good example of misunderstanding a bank. So you have the Civil War, you have slavery, where for hundreds of years you have this brutal system of labor but also of capital. Slave bodies weren’t just cotton producing, they also were collateral on which the entire Southern economy– that was an asset. Your slaves were a major asset that you could buy a lot of other things with. And so when the South and the North have this war, one of the things that Lincoln does that pisses off the south more than anything, even freeing the slaves, was to issue the greenback, which is paper money. Paper money is the first time the Constitution didn’t resolve it, because the South and the North disagreed on this one issue. Because paper money gives the nation the ability to create its own money.

And then the Civil War happens and Lincoln issues a greenback and wins both the battlefield and the money war, and then is killed, obviously. And at that point, what the just thing that Republicans at the time were arguing for, like Thaddeus Stevens, Sherman, Grant, all these guys that defeated the treasonous South were like, “Let’s divide up the land and give it to everybody, including yeoman farmers” and whatever. But instead what happened was that basically the old plantation bosses used white supremacy to divide the white poor from the Black poor. So instead of all of the sharecroppers getting land, the plantation owners got it. And cotton became a debt crop and white supremacy reigned.

So then you have Jim Crow, which was not part of slavery, neither was segregation, it was after. It was a way for the Democratic party to divide up the South to stay in that industrial cotton plantation economy. And the Freedman’s Bank was supposed to be for ex-slaves, the freed men were going to get this bank that was going to, one, keep their money safe, and two, be a means of wealth-building. And what happened was that these white managers came in and took what is $1.5 billion in today’s money, which was a lot then, and speculated it on railroad bonds and lost the money! This is money that sharecroppers were saving for homes in this bank. And it wasn’t insured by the federal government even though it had all of the federal government papers on it. And W.E.B Du Bois, who is the best historian America has ever produced and very, very prolific, wrote in his Black Week instructions a thousand-page magnum opus on the entire Southern history. And he says that if they had been in slavery another ten years, it wouldn’t have been as bad as that bank. Because what that does is, I mean, it’s just distrust. It’s a loss of that vitality. And so you see that a lot. When a bank fails with your money it is a catastrophe. And I just followed that legacy and it was racism. It was racism. Why did they have to have white managers? Why couldn’t it have been a Black manager?

if they had been in slavery another ten years, it wouldn’t have been as bad as that bank

AA: Exactly. And I just want to point out too, didn’t Frederick Douglass step in?

MB: Frederick Douglas stepped in.

AA: He tried to save the bank at the end and put in his own money and lost all that money too?

MB: Yes.

AA: I cried reading that whole section.

MB: Yeah, it was awful. And what’s fascinating about history is that when you’re in these documents, how explicitly racist it is. You are looking on the front page like “these N-words, they’re not fit to” whatever, I mean it’s really quite obvious. And so when people are like, “well, racism doesn’t exist.” You’re like, “literally it’s in the document. It’s in the contract!” Look up your deed. I had a student in Georgia do this, found my deed from my house and it says, “This house shall not be sold to anyone not white Caucasian.” It was just standard. And that’s how the Freedman’s Bank, it didn’t get prosecuted, no recourse, even though the government could have made people whole. So that’s sort of the start. And I don’t even think that’s the worst part about it. The worst part is then you get these policymakers saying it’s just that these people don’t know how to use their money and they need financial education. So it’s the theft and then the insult that it was your fault. It’s like gaslighting historically. And then after that, you can follow, and again, it’s not a conspiracy. It is the way that once slavery ends, all of these myths that were used to justify the wholesale oppression of a race, the myths being first that God said that this, then it’s racial inferiority. Those stayed because we didn’t deal with it, because America was still divided and because a lot of people in the North couldn’t admit to their role in it. And then that’s the problem. It’s like, “Oh, it’s those backwards Southerners that did it.” No, it was industrial Wall Street that also did it. And so you create this deal, and Lincoln would’ve done it. I mean, no doubt Lincoln would have fixed it, but that couldn’t happen. And so the ideologies sort of self-reproduce into new systems if they’re not dealt with.

But I’m hoping that as we educate ourselves about history and as we educate ourselves about ideology, we both free our own minds from it and also create systems whereby we can actually change things without having to do revolution in the classic sense. Because I think that’s the other thing, where people are like, “I want this to change, but I don’t like the options that we have for president.” First of all, that’s not necessarily an avenue for change. And I don’t want to do revolution. I don’t either. I don’t want any more violence, period. I don’t actually want to even punish anybody, I just want to work together. I think that’s where gender comes in. I think we need to consider what a feminine, I’m not saying female, what a feminine value system, what a feminine economy would value besides scarcity. Because women understand abundance. We can create life out of no life. You have three kids fighting, you can resolve that and you’re not going to choose one over the other two. We don’t see those binaries, we can make all three kids get what they want. You just have to be a little bit creative. So you want schools, you want roads, you want whatever, there’s no reason to have to fight about it. Why not have more?

AA: Yep, totally.

MB: And that’s the magic of money and banking, is that’s the exact thing that banks do. You trust a system and it creates abundance.

AA: If it works the way it’s supposed to work, you’re saying.

MB: Exactly.

AA: Maybe the next place we can go chronologically is what happened after the Freedman’s Bank. Because I was really interested to read that you listed all of these Black thinkers, intellectuals, and leaders, from Booker T. Washington to President Obama, Martin Luther King, saying they really supported the idea of a Black bank. MLK said to “take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit it into a Black-owned bank.” After the failure of the Freedman’s Bank there was still a lot of encouragement to put your money in a Black bank. What happened with all of these Black-owned banks for the course of the next decades?

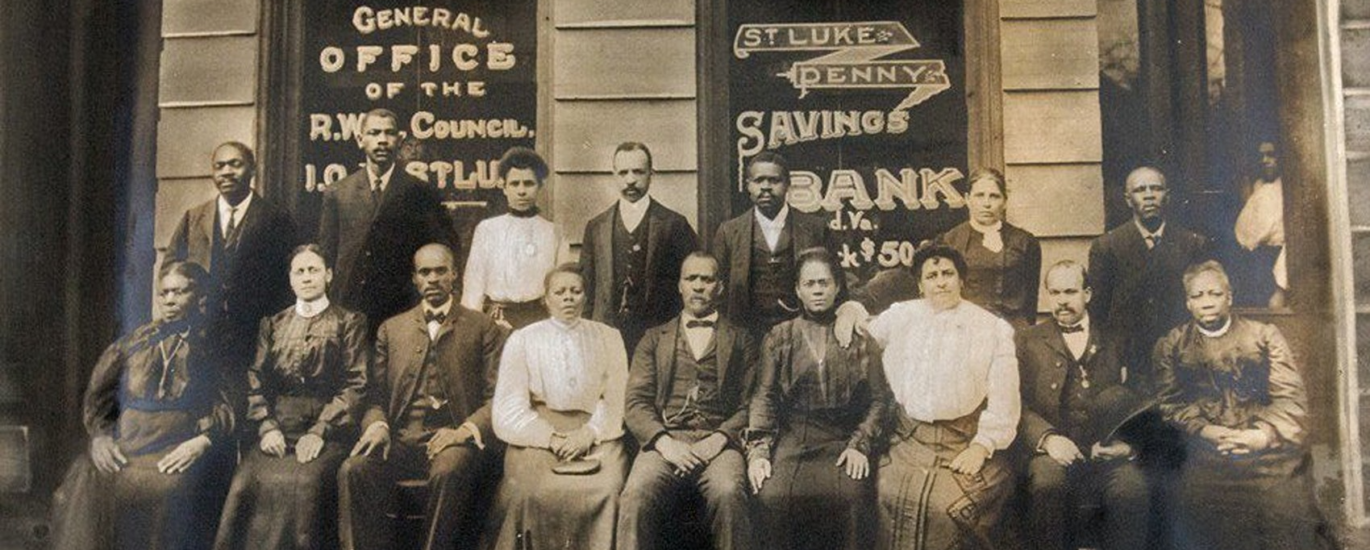

MB: Right. So, there are two different types of supporters. I did think it was interesting that you have everyone from Reagan to Malcolm X supporting Black-owned banks. But obviously it’s very different and it was just fascinating. Black-owned banks were a necessity during Jim Crow, and one of the first Black-owned banks was Maggie Walker’s bank. She was the first woman also to own a bank, and she was born a slave and had an Irish dad, I think, and abusive parentage. Her mom was fine but her dad was a little bit abusive and then she got into an abusive marriage. So she was on her own and didn’t have kids, and was part of a church society, the St. Luke’s organization. And through that she created a newspaper and she was an active person in the community. And she created a bank that was the most successful bank of any bank. During the Great Depression there were like eight or so Black banks that survived out of about 150. And it’s because of her. She gave them liquidity, she gave like 600 mortgages, and she will say her aim was for the women of her race, she wanted to give them freedom.

So a lot of them were that kind of bank. Black-owned banks were created out of necessity and they were attached to some church or society that was already doing other things. And then during the civil rights era, during every civil rights era, there had been many civil rights eras, and during those, Black banks could be a place where you could take your money out of the banks that would punish you, especially in the South. So MLK, he’s saying we need, like, look at the Montgomery bus boycott. Like a boycott to put pressure, what the banks were doing was to first not take deposits. They were mistreating, they were harassing, one Black banker said his daughter got harassed in a bank, like physically assaulted. And so he created banks so women could go and not be assaulted. And then during the civil rights movement, a lot of those banks were created as part of that whole system.

And then you have this pivot to the Nixon era that uses these Black-owned banks and Black institutions because what Nixon doesn’t want to do is integrate. So Nixon does the Southern strategy, the same thing that happened during Reconstruction, which is to get the vote of the South. And the way to do it is to give the white poor something, so Nixon does some race-baiting. As George Wallace initiated “segregation forever,” but these guys aren’t giving them anything. They’re not giving this up, they’re taking stuff. But you can rile people up by pointing outwards, right? Like, “It’s the Mexicans’ fault. It’s the Black people’s fault that you are suffering.” So that’s what Nixon does. And also very obviously this is in their archives. They’re like, “Yeah, we criminalize drugs. Why do you think we did it?” John Ehrlichman, his top aide, is like, “We had two enemies: Black people and Jews,” or something.

AA: Unbelievable.

MB: They’re very clear. Then you have the system where Black-owned banks are like, “Look, you have your banks, we have our banks. We don’t want to integrate.” And that’s also when affirmative action is. That’s who starts it, is Nixon. He has this idea of Black capitalism. This is in chapter six of my book, and I start the next book also on this moment because I think it’s a moment that we get wrong about American history, specifically in the last little bit. Affirmative action was a Nixon concession. Instead of civil rights, we’ll hire jobs and ask people to volunteer. And he did it also to divide up labor, like purposefully forcing labor because they were against labor unions too. If you give labor unions you have quotas and you have to change your whole seniority system. It got those guys angry, and so that was a benefit there.

So I’m a little bit ambivalent about the idea of Black banks because right now you can have a Black-owned bank that’s not really doing anything. It’s just a stand-in like affirmative action. You’re not changing the system that creates these disparities. You’re getting people when they’re applying to college and maybe putting a thumb on the scale, not anymore obviously, but also creating a culture war. Affirmative action has done more for the right than any other single thing because it makes people on the right think that the problem is affirmative action. Like, that’s a nothing burger. It’s nothing. And what didn’t get fixed is segregation and the racial wealth gap and the things that all the civil rights leaders were fighting for. Nobody lobbied for affirmative action. Nobody asked for that. I mean, King, X, they all got killed, but the thing that they were asking for was justice. And I think we also get that wrong, in that that was not delivered. There were laws passed, things did get better in certain ways, but they shifted toward new ideologies. And this is where we are now. I think some of those ideologies are falling apart and the danger is that another ideology will take its place rather than the thing being fixed.

AA: Can you talk a little bit more about what you call the “decoy of Black capitalism”? Can you dig into that a little bit more? Because that’s a persistent idea.

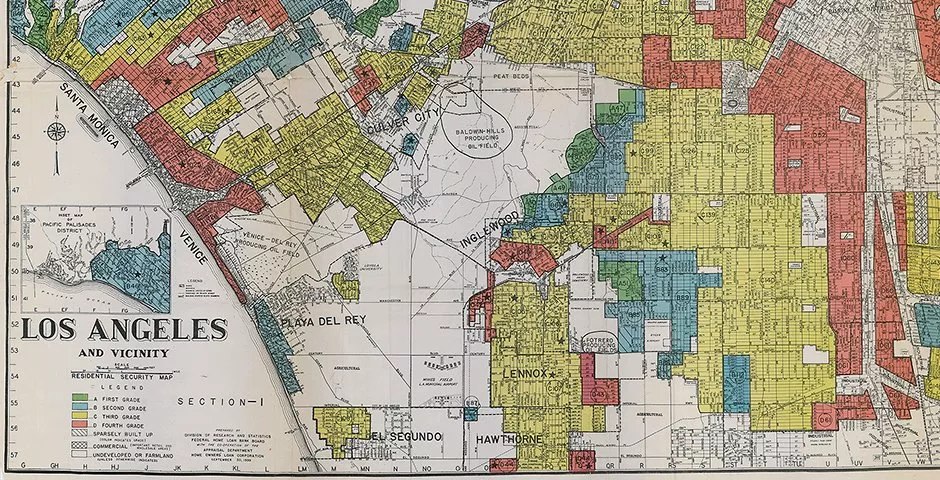

MB: Yeah. The decoy here is that instead of justice, you’ve got these segregated communities. So one community got these federally subsidized home mortgage loans from 1930, after the Great Depression, until 1970. The entire American middle class is built with this subsidized mortgage. And that mortgage isn’t available to Black people because they are Black. And in the neighborhoods where they are, it’s not available, they cannot get it. So then you have Black people in inner cities who cannot leave. Everyone else can leave, like the Irish and the Italians and everyone else that was also discriminated against, they now get to be white and go into like Levittown, these suburbs. Orange County, where I live, was basically created in 1968 from this FHA program. And you can go look at the redlined areas, you can go right now and look at redline maps in LA and see how they looked at the neighborhoods. And it’s actually hilarious. They’re like, “There are some subversive races in this neighborhood.”

AA: Oh my gosh.

MB: Literally. Like “bad Mexicans” or “low-class Polish.” I mean, it’s quite detailed and funny, but not in the way that those neighborhoods are still deprived of resources. So then those create all these others, now you have schools being funded by the taxes of the properties and they create boundaries such that the taxes can’t escape. So now you have this race to the bottom where certain neighborhoods are worth way more, and it’s bad for everybody. Because if you want to get into a good school, now you have to pay a crap ton more and gate up rather than actually integrate, which is the way to benefit all the kids. And they did it through fear. They took maybe the low-grade kind of discomfort with otherness that existed and added fuel to the fire because people also used to be really discriminatory toward the Irish. They thought that they were inherently violent. They were discriminatory toward Italians, all of those stereotypes. And within a few years of those guys being neighbors and intermarrying, those go away. So policy can change hearts and minds quickly. So then why didn’t they do it?

Well, they needed that structure for many economic reasons. When it was time to change that, and that’s where the civil rights leaders were saying this is the problem, you’ve got all of these economic systems and laws that prevent it instead of fixing it. Nixon used rhetoric around it, he twisted it into like, “You’re asking for state help and we’re going to respond with capitalism.” And neither of those things were true. It was all law from the beginning, and what Nixon was offering was not capitalism. It was neither Black capitalism nor capitalism. But the idea was that affirmative action, you’re going to earn it rather than get it for free. And that’s actually the exact language they use for the Freedman’s Bank. You should earn land, not get it for free. Earn land after hundreds of years of slavery, this is in 1865, they said, you haven’t earned this land. We will give you a bank account so you can earn it. So you see the same rhetoric that you need to earn it. And that’s where those myths lie in wait for a new demand.

And we’re all after fairness, right? We want things to be fair, and you can tell people it’s not fair. Affirmative action is not fair. And that actually makes sense if you’re a busy person who doesn’t have time to read all this history, yeah, that doesn’t seem fair. It doesn’t seem fair. But then you look at the whole sphere of it and you’re like, “Oh, okay.” So that’s what people like me do, is to try to get people interested in understanding the bigger picture and trying to contextualize all of these little things that you think it’s about affirmative action. Let me tell you where that comes from, and hopefully if someone reads the book they can not just understand the Black racial wealth gap, but also understand a lot of these myths. It’s not just about Black people. You can apply it to student loans, you can apply it to the generational divide, the fact that my students who are graduating from law school are no longer able to buy houses. And the fact that the boomers have so many houses and so much money is because of the federal grants that existed for them. They weren’t harder working, they just had more opportunities provided to them by the government. So that’s how money works.

AA: Okay. Maybe the last topic we can hit as we’re going forward in history is… As I was approaching the end of your book, I’m like, “Okay, now we’re in the years that I remember.” I thought it was so telling, and I’ll read a quote. In 1983, when President Ronald Reagan made Martin Luther King Day a national holiday, he said, “We’ve made historic strides since Rosa Parks refused to go into the back of the bus. As a democratic people, we can take pride in the knowledge that we Americans recognized a grave injustice and took action to correct it.” “We Americans,” don’t you love that?

MB: Yes.

AA: And then you write how, I mean, like you said with Nixon, using rhetoric and just talking at it as almost a smoke screen. Like, “I’m gonna do a magic trick and distract you over here by saying there’s no problem, and then I get to do whatever I want.” And you write how President Reagan consistently maintained opposition to civil rights laws because he believed them to be unnecessary and they were a government intrusion into private markets. And so maybe the last pieces that I might have you talk about are in the 1980s and ‘90s, and maybe this persists even in decades after that, with subprime loans. This was so striking to me. Subprime loans for Black Americans even in high income neighborhoods. So it really was race. It really was. They were discriminated against.

MB: Okay, there’s a lot here. Let me start with Martin Luther King, because we just had MLK Day. He’s like the most misunderstood figure in history. Martin Luther King is actually as amazing as you know, he’s not overrated, he’s underrated if anything. The things he said were way bigger than “I have a dream.” And it was also, “I have a dream,” it was also content of character, but also justice. And he was hated. The FBI had him very clearly as a number one domestic enemy. And I won’t go into how he died, but it’s clear that they were infiltrating all of the civil rights groups. And Reagan at the time was California governor and called protesters enemies. He was not a fan of civil rights and made his rise as California governor by going hard against the protesters in Berkeley and Oakland. And so when Martin Luther King, when the day became a holiday, the war’s already over, the civil rights era is crushed and there’s really no avenue. So you bring this person up to say, we’ve done it, we fixed it.

And at this point, and this is where my third book fills in a lot of gaps, a lot of the money has already infiltrated the federal government. Nixon kind of opens the door to that. And now I’m just talking about straight corruption, not just ideology. I mean, it was always a little bit of that. But here we’re talking about these think tanks that are spinning around and creating these programs. When Reagan goes in, the Heritage Foundation basically staffs his entire administration, and one of their agenda items was tax cuts. And this is, I mean, real corporate handouts. The Reagan administration completely changes Wall Street such that it becomes a financialized country. That era of greed was during the Reagan era because they deregulated the banking sector completely while cranking up the Federal Reserve’s money printer. This is Alan Greenspan constantly throwing money at Wall Street. Whenever there’s a dip or a crisis, he’s churning on the money machine.

So it’s a really cozy relationship that’s happening up there while we’re losing unions, we’re losing pensions, we’re losing jobs, not just Black people, this is lots of people. This is when things went offshore. This is when your pension as, you know, if you’re a pilot for thirty years and you had a pension, you lost it because of some corporate restructuring. The deal with the American public changes during this era, and how do you change a deal with people? How do you take away something from them? Race works phenomenally well, or the weaponization of racism and gender. And the buying of congressmen and laws became much more standardized during that era. Going to these Black-owned banks and the subprime crisis now. As Wall Street becomes unregulated and hyperdrive, money now becomes this abstract global commodity that you can grow into abundance. During the New Deal, FDR taxed income above one million at ninety-five percent.

AA: Wow.

MB: Yeah. And until the 1980s, when Reagan comes, the gap between the CEO of a company and workers, like Jim Roche was GM’s head and he made like $250k and the top paid employee would be like $100k or $80k.

AA: Oh wow. Crazy.

MB: Yes. The most you got was about five times as much. And after the eighties, it’s absurd.

AA: Yeah, orders of magnitude.

MB: Orders of magnitude, you’re different classes. A CEO before was someone who could manage the company, but a CEO after is someone who could slice up the company and sell it to private equity. For what? For parts, for finance. So then private equity becomes the leverage buyout. This becomes the financialization, like sucking the marrow out of the economy. Because private equity doesn’t add value. They say it makes things efficient, but look at hospitals, look at healthcare. They come in, and for existing industries the first thing to go is employee pensions, and second to go is employees. Because they have an incentive, and that incentive is to increase yield on capital. That incentive is not to create jobs and communities. And you’re like, well, why would it be? What is an economy for? And I think those things changed. The only thing that matters in an economy is yield for shareholders as measured in a very narrow way by this formula.

And you couldn’t make this argument like, shouldn’t a good company be one that shares with its employees, builds nice things, creates a community of beauty, whatever that is, right? JFK has a speech like, “Why don’t we measure the GDP of children being fed and going to the moon?” We can make a GDP out of anything. We can measure economic metrics out of anything we want. And the way we do it is geared toward a certain outcome. And that outcome is dividing us. It is destroying our communities, it is creating inequalities that are not just bad for the people at the bottom, but bad for the people at the top. Bad for us, the soul of our country.

How do you change a deal with people? …Race works phenomenally well, or the weaponization of racism and gender

And I don’t know of a single person that lives in this world now who feels like things are fair. Like, “My kid has the same chances as any kid, regardless of–” nobody thinks that. And the fact that nobody thinks that is scary, because if I don’t think that, I’m an academic so I’m going to spend my time writing about it and thinking about it. But you see historically, when you have inequality like this, there are scapegoats and fascists that promise people they will fix it. People understand that something’s wrong. And the problem is that everyone has these theories, and some of those theories end up regurgitating some of the worst ideologies in history. And they’re going to be racist, they’re going to be sexist, and they’re going to go away. That’s the problem.

AA: Yep. One of the really most heartbreaking stories that evoked the Freedman’s Bank of the earlier century was Jackie Robinson’s Freedom National Bank of Harlem. Can you tell us about that?

MB: Jackie Robinson, if people know, he integrated baseball. He went to World War II in the first integrated troops, he was like a national hero, a really good guy. He creates this bank in Harlem, the Freedom Bank, and he’s a rich guy and he’s doing it for the community. He realizes that Harlem doesn’t have a Black bank, and a lot of these banks start in that same way, just out of the goodness of his heart. And he is stuck, as are many Black bankers, between wanting to help his community and being in this trap. Because the thing that’s important to understand about Black banking, which we didn’t talk about and which is kind of what my book is about, is that unless you are plugged into that machine, that money printer, it’s impossible to do banking. That was the original idea of this book, was to let me show you how banking works by showing you what happens when a bank is outside of that structure. And the problem is that you’ve got deposits that are volatile for people, the homes that you’re lending to are underwater, you’re not getting any of the goodies from the federal government, and it’s impossible to bank.

It’s a trap, and I follow it through. It’s tragic reading these memoirs, I mean, for Jackie Robinson the regulators are breathing down his neck because he doesn’t have the numbers. And then the community is like, “You’re a capitalist bad guy because you’re not giving these loans.” It’s so stressful that the bank essentially kills him. He has high blood pressure and he’s like a fifty-five year old guy, he wasn’t old and he had done all of this amazing stuff, and it’s because of the bank. And he writes about it in his memoirs and it’s the saddest thing ever. I’m reading this as someone so far out in history and having studied this, and he’s talking about the bank and it’s like he blames himself. He’s like, “I just don’t think I was good enough at it. Maybe I didn’t try enough.” And you’re like, “No!” I read about his death and it was just stress. And nobody says it’s the bank, but he was under regulatory supervision. It wasn’t doing anything wrong, but he just couldn’t make it work.

And then that bank, when it did fail in the ‘70s or ‘80s, the FDIC comes in and does this weird thing where they just liquidate the bank for unknown reasons. Usually when a bank fails, they sell it to somebody else. But you look back in history and Harlem, which had the biggest Black population, didn’t have a bank for the time that they should have, when the Renaissance was happening. When Chicago had like five Black banks, Harlem had none. And the reason is because Chase Manhattan liked to take deposits in Harlem and lend them downtown. And Chase was also part of the state banking commission that could deny charters. And so there’s all these banks that are trying to get charters and they’re not getting them.

AA: So it’s actually creating wealth for white people, essentially.

MB: Yep.

AA: They’re taking Black people’s money and the money is being siphoned, almost, and it’s growing but it’s enriching the white community.

MB: Exactly. Like I said when we started this conversation, a loan is how you make money.

AA: And they won’t loan to Black people.

MB: They won’t loan. And the reason they wouldn’t loan, and I read this in a PhD dissertation by this guy who was very proud of saying this, he’s like, “They weren’t entrepreneurs, they weren’t business.”

AA: Oh my gosh.

MB: So it’s like the shoe shining thing. Like, we are not giving you a loan because you’re not an entrepreneur. Well, give me a loan and let me be an entrepreneur! But that systematic way of nobody getting loans, and therefore, how could you be an entrepreneur?

AA: How could you? Yeah. Oh, it’s so heartbreaking. Well, what’s the state of things today? And as my final question, is there anything that listeners can do to help?

MB: Learn and be aware. I think most people know their own expertise. Use your own expertise. I’m here to give you, like, I wrote this book for no other purpose than to get this story right, so read that if you’re interested. And then when you can unravel one myth in your mind, I think that’s a power that you get that helps with all sorts of other things. And it’s like this passive thing I see in teaching every year. You almost don’t know you’re learning, and you kind of take for granted all the stuff you know. If I take my students from the first day of law school and I have them until the end, there’s so much, there’s a way that their mind works at the end of the semester that they didn’t have before. And I see that every year. It’s like, “You guys have no idea how to think,” and then by the end they’re just like– And that’s how it is when you read and understand history. I think it allows you to see the world in a more rich, empathetic way, and you can extend that empathy. Like you said, it’s heartbreaking. You can extend the circle of care beyond the people that you know by knowing more about these histories. So use your own inspiration.

AA: Awesome. Well, thank you so much again, Mehrsa Baradaran. Thank you for your work, thank you for this book. I learned so much and I’m looking forward to your next book. I really appreciate you being here today.

MB: Thank you so much, I really appreciate this. And thank you for doing this podcast, it’s such a great resource to have, and I hope everyone listens to all of them.

Patriarchy…

when you see it, it’s everywhere.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!