“they could have stopped it by picking up and going back home.”

Amy and Meleseini Lotoaniu conclude their discussion of gender constructs in Tonga, from European contact to the present day.

Our Guest

Meleseini Lotoaniu

Meleseini Lotoaniu is a third-year student at University of California, Davis with an interest in literature and writing.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: This week we’re sharing our second episode in our series on Gender Constructs in the island kingdom of Tonga. And I’m so happy to welcome back Meleseini Lotoaniu for today’s conversation. Hi, Meleseini!

Meleseini Lotoaniu: Hi Amy! So happy to be here.

AA: Okay, so we’ve shared a bunch about Tongan culture before European contact, and now we’re going to talk about some of the changes that happened once boats started to arrive from Europe. So, Meleseini, can you tell us some of the main points of what happened in the Tongan islands once Europeans started to arrive?

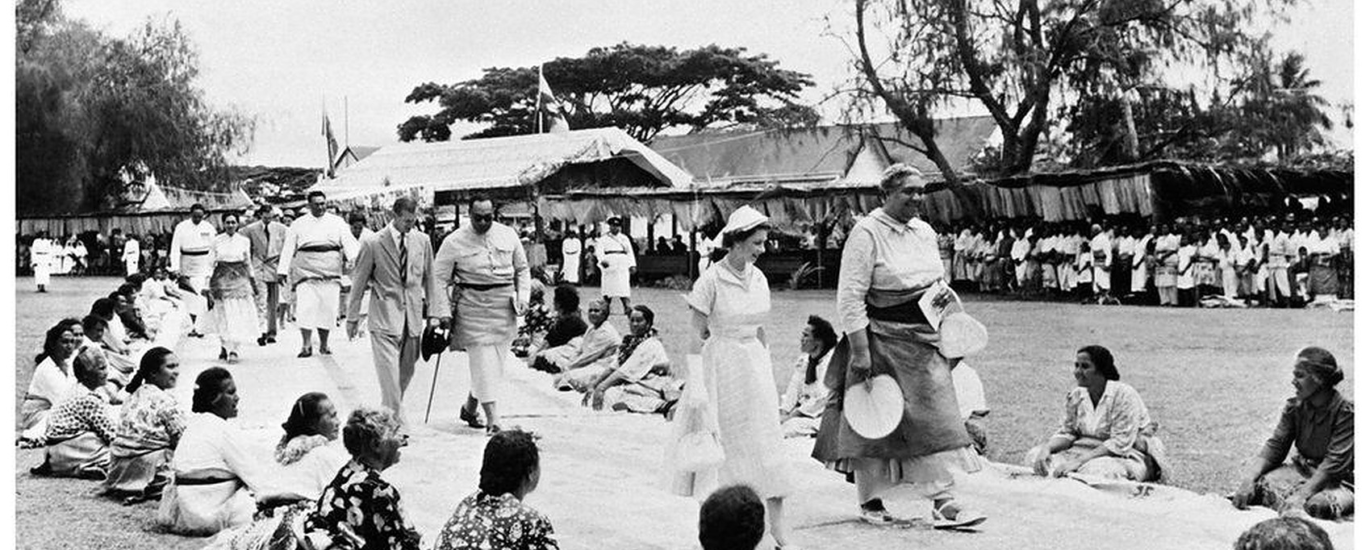

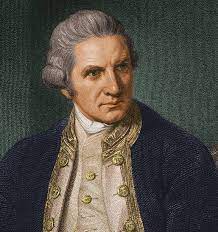

ML: When the Europeans first arrived, the Tongans called them the palangi, which meant clothmen because the Tongans respected the different and useful fabrics that the Europeans used for clothing and boat sails. The first European explorers who landed in Tonga were Willem Cornelisz Schouten and Jacob Le Maire from the Netherlands in 1616. And after that, one more European landed there in the 1600s and one more in 1767. But then there came a really famous explorer, Captain James Cook. Captain Cook was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy. He was famous for his voyages to New Zealand, Australia, and Hawai’i. So Captain Cook first landed in the Tongan islands in 1773 during his second Pacific voyage. In 1774 he returned for four days and received such a warm welcome that he named Tonga the “Friendly Islands”.

Every couple of decades another European ship would show up. The most important ones after Captain Cook were the ship Duff in 1797 which brought the first missionaries to the islands. The traveler ship, the Port Au Prince in 1806, which brought travelers who lived in the islands for four years. And they were important because they later wrote memories of their stay. And one of them was William Mariner, whom we will hear a lot from in the next section. William Charles Mariner was an Englishman who lived in Tonga from 1806 to 1810. And he published a memoir called An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, which is one of the major sources of information about Tonga before it was influenced significantly by European cultures and Christianity. And so he actually interviewed some upper-class men about gender relationships back then. And so relating it back to me, I think I have a copy of that back home. I think my father may have this back home in the area.

AA: Really?

ML: Yeah, but I never read it technically. But now that I know more about it, I’ll definitely go back and see.

AA: Was it just like on the coffee table or something?

ML: Yeah, yeah. My father has a collection of other Tongan books, and I think that’s one of them. Now that I’m older, I’ll definitely go back and read it.

AA: That’s so cool. That’s so interesting.

ML: Yeah. And so going back to the European contact, more regular contact including cargo ships and later whalers actually began after 1810.

AA: So I’ll talk a little bit about what the Europeans wrote about Tongans when they arrived, what their observations were. One super fascinating part for me was that the Europeans’ assessment of Tongan culture when they arrived varied according to their own cultural beliefs and the trends that were going on at the time. The author of the book talked about how the 17th-century Dutch explorers came from a really strict Protestant background that valued rigid rules and a vigorous work ethic, and so they perceived Tongan culture pretty negatively when they arrived.

There was a quote that a Dutch explorer wrote: “They are without religion as brute beasts and have no knowledge of merchandise, like living primitives would. Without laboring, having for food the fruits of the trees and fish quite raw.” And another thing that they wrote was, “The people live miserably in little huts along the shore. No furniture but some dry grass to sleep on. The king himself had nothing else in his hut.” Just so interesting. Like, you hear that, right? You hear “They don’t have religion!” I mean, they did. They just didn’t have a European religion. But also, I thought it was so interesting “they don’t have a knowledge of merchandise… they just take fruits off trees, like where’s their hard work ethic? And they just eat the fish from the ocean…” So they perceived that really negatively based on their cultural expectations and what they valued. And again, it limited even their ability to see that these people actually did have a really rich and complex life. They just couldn’t understand it.

So contrast that with the next century, where you have Europeans arriving in the 18th century who had been influenced by the values of the Enlightenment, where Jean Jacque Rousseau and other philosophers had praised the “state of nature” as the ideal way that humans should live. And so these Enlightenment-informed explorers thought the Tongans seemed superior because they were living a more natural life. They were less corrupted by society in their view. They praised the fact that Tongans were never hungry, they said no one wants the common necessities of life. They saw that as a good thing. They reported the orderly conduct of everyday life, they reported the balance of industriousness with a lot of leisure time. And they saw the sexual flirtatiousness balanced with marital fidelity and they thought, this is wonderful. So they were kind of shocked by lots of things. And one of the things that they wrote specifically is that there were female boxers, like women fighters, which was really interesting. But Captain Cook and William Mariner in the 18th century both expressed concern that European contact was already beginning to have a negative influence on Tongan culture. Which again is kind of an Enlightenment value that these people living in a state of nature, like “oh no, we don’t want society (“society”, European society) to corrupt them too much.”

ML: Yeah, and I think that’s really interesting too because I wouldn’t really expect that these European explorers would think of European contact affecting Tongan culture in that way. I would think of them as being ignorant. I’m just really surprised that they expressed concern about that.

AA: I am too. I wish they’d done more about it, but it is interesting that they thought about it.

ML: Yeah, they could have stopped it by picking up and going back home.

AA: That would’ve been even better, yeah. The next part that we wanted to talk about were the European comments specifically on the status of women when they arrived. Meleseini, did you have some parts of the book that you thought were interesting on that topic?

ML: Yeah. So, one of Captain Cook’s officers, which was the ship doctor named Dr. Anderson, had noted in 1777 that Tongan women “have great sway in the management of affairs.” But they also noticed that “they were surprised that women did deep sea diving and handled the paddle as dexterously as the men. Cook remarked on his confusion about authority and deference behaviors, particularly where certain men bowed down on the ground to certain women.”

AA: So they would not have been used to seeing a man bow to a woman in any context except if there was a queen of the country, right? So this complex interplay of statuses was probably really surprising.

ML: Yeah, really weird to them. And so according to Mariner, “As women are the weaker of the two genders, it is thought unmanly not to show them attention in kind regard. Women are therefore not subjected to hard labor or any very menial work. At meals, strangers and foreigners are always shown a preference, and females are helped before men of the same rank because they are the weaker sex and require more attention.”

they were surprised that women did deep sea diving and handled the paddle as dexterously as the men

And Mariner came from England, so he came from a culture that placed women on pedestals because they were weaker. He had a chivalry and ladies-first mentality so when he saw women eating first, he sort of attributed that social custom to a belief that women were weaker. But in actuality, many of those women were probably eating first because they outranked those particular men. Once in front of these European sailors, a female chief insisted that a male relative of hers who was an up-and-coming chief himself publicly bow down in front of her and she placed her foot on his head. She told the Europeans present that that man was bound to pay her these marks of respect because it was from her that he derived his dignity.

And one last thing that we found interesting was that Captain Cook’s officer observed that “when women cease to bear children, they appear to gain instead of lose respect.” So I guess women weren’t really seen as just people who bore children, you know, they were seen as more than that.

AA: It guts me to think of how in our culture, women do just really lose value, and especially back then too in Europe. And that’s probably why the men noticed it. Like, “whoa, these elderly women are really revered.” That would’ve been completely foreign to them, right? I noticed that part too, and thought that was really the way it should be.

One part that I wanted to talk about in terms of gender roles among Tongans was the issue of men committing violence against women. Most sources agree, as you just pointed out, Meleseini in that quote that men would exercise their power in a very gentle manner except in a few cases. And that seemed to be what a lot of people reported. They said that Tongan women enjoyed high status relative to European women of the time, and they were relatively immune from everyday violence. Travelers described household dynamics as pretty tranquil and that people who were married to each other were really affectionate with each other.

But at the same time, extramarital affairs could result in a man beating his wife. And if a chiefly class young woman had premarital sex, then she could be beaten even though she was of the chiefly class. But in general, wife abuse was exceedingly rare and at least in some cases it was really punished. And in some cases it resulted in capital punishment. So if a man beat his wife, he would be killed. Which, again, is so different from what Europe was like at the time. Also rape was known but very, very rare according to the Europeans writing down their observations. If a woman was married and she was raped, then that man was punishable by severe beating and public shaming, or even death. If the woman who was raped was unmarried and chiefly, the man would be killed and his entire kindred would be endangered. And interestingly, that action would be considered criminal, not only because she was unwilling, but also because he was lower ranking than she was. Rape also occurred most often during war, which is still the case among humanity. When women were captured, then sometimes they were used as sex slaves, whereas they would just kill men. Rape during peace time was again very rare, but it was most often perpetrated by chiefly men against the Tua women.

Mariner wrote, “With respect to the wives of the lower ranks in society, they are oftener to be met with alone, and on such occasions, sometimes consent to the solicitations of chiefs whom they might happen to meet. Not from any abandoned principle or want of affection to their husbands, but from a fear of incurring the resentment of their superiors.” So again, a higher ranking man could meet a lower ranking woman on the road where nobody’s around, and she would have to do what he said because he was higher ranking. And again, I just thought this is so relatable, I think throughout all time. It just sounds familiar, doesn’t it, Meleseini? I mean, it sounds like Trump saying that he could grab women by their private parts and there’s nothing they could do about it because he had more power than they did. So it just sounds like no society is immune from those kinds of abuses.

But that leads to some really interesting things also about sexual dynamics between men and women. One part that I thought was interesting was there was this concept of the village child. So a village could send an unmarried woman to a male chief just for his use, basically, until she conceived. And then the subsequent child would be called the village child, and this child would be revered along with its mother because it had a connection to this chiefly class. And so one can safely assume that this brought favors from the chief to the whole village. And the author points out that “the willingness or unwillingness of the young woman is not known.” But that is one way that we talked about earlier, that men couldn’t really use women as pawns, but in that way women were kind of used to increase the village’s status and get favors from the chief, which was interesting.

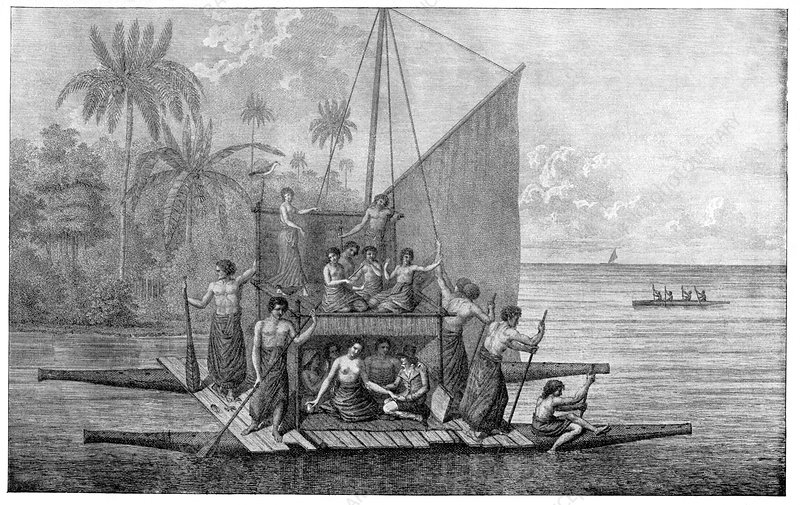

Another thing was that early European travelers, like sailors, were sometimes approached by unmarried Tongan women to have sex in return for objects. And one of the things that Tongans were most interested in and would want to pay for in all kinds of ways was nails, like iron nails. Which you can imagine if you didn’t have nails, it would make it a lot easier to build things if you had nails. So nails were really valuable, cloth was really valuable, axes, knives. And when young women would come onto these boats and make sexual advances in exchange for these objects, the Europeans interpreted this as prostitution, which is indeed what it sounds like. But the author points out that it’s possible that these young women may have been acting according to the wishes of the higher ranking relatives and their communities. And that is what it sounds like to me. It just doesn’t sound like something that young women would want to do on their own. It sounds to me like someone higher up in the village was probably putting them up to that, to go get nails for the village. So that was the sad part.

Mariner commented that unmarried women may “do as they please, without any shame or disgrace until marriage.” And so he was probably referring to non-chiefly women since the higher the rank, the more closely a young woman was monitored sexually. So the lower ranks could have sexual relationships pretty freely and there was no shame in that. Premarital sex was much more common and their attitudes towards sexuality were a lot more open and matter-of-fact than in Europe. Neither men nor women wore any clothing on top, and Captain Cook’s officer Dr. Anderson described “both men and women seem to have little knowledge of what we call delicacy in amour. They rather seem to think it unnatural to suppress an appetite originally implanted in them for perhaps the same purposes as hunger or thirst. And consequently make it often a topic of public conversation. Or what is more indecent in our judgment, have been seen to cool the ardor of their mutual inclinations before the eyes of many spectators.” So obviously just much, much more open about sexuality.

We mentioned earlier that chiefs often had multiple wives, and Europeans observed that these polygynous families – and again polygynous, “poly” means multiple and “gynous” like gynecology that just means women, so many women. So these families were quite peaceful and the Europeans were surprised that there wasn’t a lot of fighting between the wives. And Dr. Anderson explained this harmony in the following way: “This harmony may in a great degree be owing to the absolute power each man has over his own family. Every woman being so much at her husband’s disposal as renders her liable to be discarded on the smallest displeasure.” So this is one part of the book that I really questioned the source of this information because I think he was bringing a lot of assumptions with him. Because the fact was that in Tonga, those co-wives, those sister wives were often literally sisters. They were close relatives. The first wife in a polygynous relationship chose the other wives, and so she would often choose her sisters or her cousins. And as you pointed out, Meleseini, there wasn’t even a distinction. So she would maybe just choose her female family members whom she loved, and maybe that’s why there wasn’t very much contention between the wives.

The other thing is that divorce was really simple. It was still at the discretion of the husband, but the cultural norm was that if a wife said she wasn’t happy in the marriage, the husband would just say, that’s fine, you’re free to go. And she could leave. She could remarry if she wanted to without any shame, or she didn’t have to remarry because her status was secure in the society without being dependent on the status of her husband. And so marriage wasn’t an economic arrangement that made women financially dependent on their husbands the way it was in Europe. Women were fine on their own. So if wives didn’t like the marriage arrangement, they could leave fairly easily. So that’s a really different situation. And so maybe the plural wives didn’t fight because A) they were friends, and B) they could leave easily if they didn’t like it. So that was one example of the source of the information being a little bit suspect. Meleseini, could you tell us some ways that European contact changed Tongan culture?

ML: Yeah, sure. As I mentioned earlier, Tonga was never technically colonized. There were colonial administrators who were officially advisors, but not governors. And land was not seized or purchased by foreigners, but processes associated with colonialism deeply influenced the development of class and state structures. When the first Europeans arrived, Tongans gave gifts without expecting anything in return. And they seemed happy to receive gifts, but soon they learned how the Europeans did things and they started bartering. The most prized items that Europeans had were axes and especially nails, as Amy mentioned earlier. So it was common for female chiefs and especially old women to trade with the European visitors, actually.

AA: Okay, and I have to just throw in here, it said that female chiefs and especially old women would come out to the sailors’ boats to be like, okay, let’s conduct a trade. I’m just imagining these sailors with their jaws on the floor. Can you imagine old European women being the representatives in trade or government? Like if a visiting country pulled into a port in 18th-century England and the people sent out to conduct the trade were elderly women, it just… It’s unthinkable to me. And it makes me sad that it’s so unthinkable to me. Why wouldn’t elderly women be the revered members of society to conduct business? But yeah, it must have just been shocking for those sailors, haha.

ML: Yeah. And so going back, some of the most important ways that European presence changed Tongan society were the new weapons that increased warfare between chiefs. So I’m guessing it was more peaceful before the Europeans came and had all these new weapons that the Tongan people would’ve garnered interest in. And so it must have disrupted, I would say, the social tensions between chiefs. Another thing was that some people accumulated more European wealth than others, which caused class divisions. Some Europeans felt it was inappropriate for women to do the more lucrative types of production, so they ensured that these high status and high wealth jobs were assigned to men. The objects that had been considered valuable because they were made by women lost their value.

And of course, one of the most influential factors that changed the culture was Christianity. In 1797, that’s when the missionaries first arrived in Tonga, which were sponsored by the London Missionary Society. The group consisted of nine men and they landed at Tongatapu, the main island. The evangelicals were befriended by Mumui, who was a very important chief. The missionaries used some white residents as interpreters. There were some white people who had lived in Tonga for many years, most of them were castaways, but some were escaped convicts from New South Wales, which is now known as Australia. And they were a pretty rough bunch, so it was kind of weird that they would be working with missionaries. The first attempt at building a mission ended disastrously, with all the missionaries causing such problems that they were killed by Tongans or fled back to England.

soon they learned how the Europeans did things and they started bartering

When the missionaries returned to the islands, they wanted to convert people, but also generate funds to make the mission self-sufficient. They wanted to “lead them into habits of industry to which they are strangers. For though they are more industrious than most of their neighbors scattered about the sea, far the greater part of their time is spent in idleness.” So they were training the people in religion, but also purposely in capitalism. The group of missionaries selected were chosen for their trades as smiths, carpenters, medicine and business, “highly necessary to impart the principles and habits of civilization to the South Sea islanders.” And so the missionaries’ conversion strategy included a top-down approach, attached missionaries to powerful chiefs, convert the chiefs and help the chiefs consolidate their control over other groups. From the outset, the missionaries ignored all other forms of authority in favor of power and protection. They ignored considerations of high rank. For example, they did not treat female chiefs in the same way that they treated male chiefs who had similar rank. In the 1820s, Wesleyan Methodist missionaries began proselytizing on the islands. They began converting the chiefs, the most influential of whom was an ambitious chief named Tāufaʻāhau. He was a chief on the island of Ha’apai, but he wanted to control other chiefdoms on the other islands. And so when missionaries converted him in 1831, he renamed himself King George after King George III of England and proclaimed himself King George of Tonga. Just think about how incendiary that would sound to the other chiefly groups who had had authority over their kin groups for thousands of years!

Some chiefly groups embraced Christianity, some tolerated Christianity, and some actively opposed it. The missionaries actively taught that all of Tonga needed to unify under one Christian chief and form a centralized government as European countries did. So while some of the non-Christian chiefs were willing to tolerate their fellow chiefs’ new religion, like you do you, the newly converted Christian chiefs were not willing to let other groups do their own thing and keep their old traditions. So Christian groups supported by the missionaries attacked non-Christian groups, leading at times to open warfare between the two ideologies. On one side the Christians, and on the other, the traditional community who wanted to maintain their way of life.

In a church sermon in Tonga in 1837, missionaries taught their converts that this battle was “the clash between Jehovah’s chosen people and the heathen opposition.” One Sunday, the traditional faction raided the gardens of the Christians while the Christians were in church. In retaliation the next day, the Christians stormed the traditional community’s fortress, burned it, killed twenty people, and took everyone else prisoner. A week later, after another raid on gardens during church services, Christian forces attacked and destroyed a fortress. The Christians killed 300 women, men, and children. The slaughter was not in accordance with Tongan custom. Even some of the Europeans in the islands were horrified about what was happening. They could see that the Tongan King George wanted power and the missionaries felt justified annihilating anyone who resisted Christianity.

In 1852, the English ship captain, Captain Charles Wilkes, wrote “The traditionals desired peace and to be left in the quiet enjoyment of their land and their gods, and they did not wish to interfere or have anything to do with the new religion.” He did not see the traditionals as heathens. He also wrote, “The missionaries describe the Tongan people as a set of cruel savages, great liars, treacherous and evil-disposed. And this character seems to be given to them only because they will not listen to the preaching and it is alleged they must therefore be treated with severity and compelled to yield. I must here record that in all that met our observations the impression was that the heathen were well-disposed and kind and were desirous to put an end to the difficulties.”

AA: Doesn’t that just break your heart? I hated this part. It was awful. And to read those instances where the traditional people would raid the Christians’ garden and then they would retaliate by slaughtering 300 people. Oh, so hard. I don’t know, it’s awful.

ML: Yeah. It really shows the religious tensions, like how far people will go when they’re divided by their ideologies and their religions.

AA: And for power.

ML: So next, the French sent Catholic missionaries to Tonga, which complicated everything further and caused more war. And some Tongan chiefs ended up converting to Catholicism. Their descendants remain Catholic to this day. King George ended up ruling Tonga until he was 95 years old in 1893. He consolidated power and some sources I read claimed that because he was Christian and allied himself with Europe, European leaders respected him and thus never colonized Tonga. Another interesting thing about King George is that during a trip to Australia and New Zealand in 1853, he noticed a lot of indigenous people who were beggars. He was told that they were unable to work since they had no land. This led to the constitution stating that land in Tonga could only be given to natural-born Tongans and not sold to outsiders. This is still the case today in Tonga. Native Hawaiians have been priced out of their own homeland by foreign investors, so that was some positive impression that King George handed down.

AA: Yeah, I thought the same thing. That was really interesting. Had you known that too, Meleseini, that only a native-born Tongan can own land? You can’t sell it to an outsider?

ML: I didn’t know that before that only natural-born Tongans could own land in Tonga, but I do know, I guess really only Tongan people can own land. Even Tongan people who were born overseas, like land that they might have inherited from their own family members could definitely be passed down to them. But I’m not really surprised that foreign people can’t own land in Tonga. Which is a nice contrast, I think, it’s an interesting contrast to land in Hawai’i.

AA: Yeah, exactly. Okay, going back really quickly to this topic of religion, Meleseini. And this goes back, this is why I introduced in the very beginning of the episode with my friend Malia and her family saying, “should we do things the Tongan way or the church way?” And kind of feeling that schism inside, like even in your emotions, and your psychology, and your family. Like, I have this traditional part but then I also am a believing Christian. And I know you’re Christian, Meleseini, and I think if I were Tongan and Christian I might have a hard time with this part of the history. How’d you feel as you read that?

ML: I’m just now learning about this, that this is how Christianity started in Tonga. I knew it came from European contact and everything, but now just hearing about how there were battles and people were killed over this, it’s just really discomforting, I would say. Yeah, it’s really saddening.

AA: Well, the conversation is not going to get much easier because we’re now going to talk about Christianity’s impact specifically on women in Tonga. One main goal of missionary expeditions was to tame and domesticate Tongan women. They were seen as very sexually free compared with European women, and they were. Some young women apparently came on board European ships and made very blatant sexual advances toward the sailors, which many sailors didn’t complain about, but some did, and they saw it as temptation and they didn’t like it. And so some changes that Christian missionaries made to Tongan culture that directly addressed women were the following: First of all, Christian missionaries imposed their own separate spheres ideology on what was proper men’s work and what was proper women’s work. This was a really difficult transition, because as we talked about before, everybody could cook a little bit, but to have a specialization that was cooking was demeaning to women. Because to be a cook was men’s work. So that was very difficult to adjust to. Another thing was that Christian missionaries actively discouraged the exercise of fahu, and they did this for three reasons.

First of all, because of the influence that it had in keeping married women independent of their husband’s authority. Because like we talked about, fahu would maintain that authority and status in their family of origin. So a second thing that made it incompatible with a European model was because the fahu system violated the Christian capitalist emphasis on private property. Because through the fahu, a sister could simply take goods and food from the brother’s family if they needed them. Families could be reliant on each other and share, and that undercut the missionaries’ attempt to instill the virtues of accumulation through your own hard work and not relying on somebody else. So they saw that as a threat also to what they thought was the superior way of life. And a third thing was that they wanted to stamp out the fahu system because it allowed women to inherit property, and that was deemed improper. The only proper system of inheritance was patrilineal, from father to son. So fahu rights were considered heathen and they were forbidden by missionaries and they were legally outlawed in the 1920s. So while fahu continues in influence and in personal and family custom, legally women lost their privilege and authority that had come from the fahu system.

Another big change was that missionaries made sex a wifely duty in marriage. In traditional Tongan culture, after a woman gave birth to a child, that new mother would be secluded for a month and she would be cared for by women from both sides of her family. And that mother was supposed to refrain from sexual intercourse until the baby was weaned because another pregnancy would cause hardship to that mother, and that would be hard both on her body and also on her ability to care for another baby too soon that she wasn’t ready for. So this just made me so furious. The missionaries forbade this custom of having the mother go into seclusion with her family, and they forbade abstinence after childbirth and they forced the mothers to wean their babies from nursing earlier. Just the thought of male foreign missionaries coming in and getting into this intimate business of women and their husbands and their babies made me cry. I was so upset. It makes me so angry. By the 1900s there was an increase in infant mortality and Tongans attributed this, at least in part, to women weaning their babies too soon because of that disruption in their traditions.

Missionaries also adjusted divorce law, making it much harder for women to leave unhappy marriages. Another change was that women who were found guilty of fornicating faced prison sentences, or really stiff fines or having to do public service. And fornicating just meant any sex outside of marriage, which hadn’t been shamed before. Another change was that missionaries forced young women to grow their hair long like European women. Prior to that, Tongan women had their hair cut short. That was their tradition and European men thought that that was inappropriate. They thought that short hair was man-ish, and so they forced women to grow their hair out. They also forced women to cover their breasts, and early accounts say that missionaries were super frustrated because the women were required to make a fabric covering like a shirt or whatever, but they would wrap that fabric so loosely that it would just fall down. And the missionaries got annoyed because they’re like, ugh, they don’t even feel any sense of shame about their breasts. The fabric falls down and they don’t even adjust it. They don’t even notice that their breasts are showing. And I was like, yeah, of course! Because they’ve grown up their whole lives with that not being a sexual part. So that would be like, would I notice if my shirt sleeve fell and my wrist showed? I wouldn’t even notice because that’s– Anyway, it’s just frustrating. So then all of these changes were met with huge resistance, and that in turn resulted in severe punishment such as public floggings and breaking women’s teeth, branding their shoulders, and forcing them to do labor on mission plantations if they broke these rules.

Our last topic that we wanted to cover today is some modern features of Tongan cultures regarding gender. So Meleseini, I wanted to ask you, do people have equal rights in Tonga?

ML: Tongan women barely just got that right to vote, less than a hundred years ago. So I would say most gender rights are, well, I think they’re getting there to be equal but it’s just like taking some time. Another big thing in Tonga was that women couldn’t own land. Only men could, well, technically the land could only be inherited by male members of the family. So I think that that was a pretty big thing, well that is a pretty big thing regarding gender rights in Tonga right now. And the way they justify it, I would say definitely it comes from the same sentiments of the early European contact when they came and saw how basically women were free, women were allowed to do anything before European contact. And so when the Europeans came in, they really changed the trajectory of how women were treated and how women could live in Tonga. So I think it’s still just like the reeling aftereffects of European contact that came in and basically changed how women’s lifestyles work.

AA: Do you know of any initiatives in Tonga right now to change that policy of women not being able to own land?

ML: No. I did actually try to do some research, but most of it that I found was from the early 2000s. But recently, like within a few years, I haven’t found any recent initiatives.

AA: Okay, that’s really interesting. It’s really surprising to me that women are not allowed to own land, and one of the reasons, not a reason, one of the justifications that people gave was that it’s better for women because it means they don’t have to pay property taxes. The stupidest reason I’ve ever heard, that’s just such a silly, silly justification!

ML: That is absurd.

AA: So how would you characterize some of the challenges that still exist in Tonga for women?

ML: Yeah, husbands have generally higher authority than wives in both public and private spheres. And still men are generally considered to be the main decision makers. Which is interesting because of the traditional high regard for women, it’s interesting to think of it like that because many Tongans still do not regard gender issues as a concern because of that traditional high regard for women. And so although women in Tonga are still generally treated with respect, they still face various forms of inequalities in the highly stratified social system. But fundamentally, women’s privileges are not officially recorded in any way. And I think it stems really from Tonga shifting to a religious and conservative society since Tonga was never officially colonized, but we’ve now just discussed the various Western and European influences that definitely reached them over there. And so I think it stems basically from religious values or people trying to use religion to control and take advantage over others.

And another issue of Tongan women’s rights include women’s low participation in government. Some say that they don’t want women to participate in government because they want to protect the Anga Fakatonga, the traditional Tongan way of life. Which could mean that women are still given this highly respected rank but it shouldn’t be up to them to make important decisions, you know? So I think this reinforces this patriarchal structure where only the men’s sides will be heard. And so does that mean that the Anga Fakatonga only means that it should be catered towards men’s voices, or shouldn’t it include everyone else’s voices? I think there are possible ways to get around that.

AA: Well, I also think it’s ironic hearing you say that they call the Anga Fakatonga the traditional Tongan way of life, but what they’re harkening back to is actually the European way of life that was imposed on them, like you just said. So it’s really ironic that they call that now that’s considered traditional Tongan when it’s actually not I. Am I understanding that correctly, Meleseini?

many Tongans still do not regard gender issues as a concern because of that traditional high regard for women.

ML: Yeah, I think that’s how I see it too. It really just all stems from European contact coming in and disrupting the actual Tongan way of life, where Tongan women were more carefree and they had a much more involved role in the Tongan way of life.

AA: Another argument that I heard that kind of happens all over the world for like, “no, we don’t need to change anything” is that there are more pressing issues in the society. I don’t know if that’s an argument that people make in Tonga, but like, we don’t need to do women’s reform because women are fine and we have way more important things to do. What do you think, is that an issue and what do you think of that if so?

ML: Some people might argue about having political reform and economic development as a more pressing issue, but I think that will always be an issue. So it’s just time to prioritize women’s rights and they’re just as significant as economic development and political reform. And maybe working towards women’s rights could be an advantage to dealing with those other issues of reform and development. I think it’s just time to modernize, basically. This is the 21st century where the world has evolved so much, and gender rights should be the focus.

AA: Yeah, when you mentioned that there aren’t any codified protections of women’s rights in Tonga, so women may be treated well in general, but there aren’t official protections. One thing that I thought of was CEDAW. In 2015, the United Nations had a convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women, that’s where you get C-E-D-A-W, and that’s supposed to be the international bill of rights for gender equity across the world. And so some countries said yes, we ratify this initiative. We are going to try to comply with all of the requirements that CEDAW put forth. You know, recognizing the equal dignity and value of all human beings. We can’t discriminate against women anymore. But Tonga has not really made an effort to ratify or comply with CEDAW. So that would be maybe a place to start. If we’re talking about gender equity, then that and land ownership is one that I read a lot that were two big problems that feminists in Tonga are talking about.

Well, thank you so much, Meleseini. This has been a really important book for me to read. I learned so much and I really, really enjoyed talking with you. I’m wondering if we could wrap up by having you share a takeaway that you got from this project?

ML: Yeah, definitely. One takeaway really is just the impact of European contact and how they brought their religion to Tonga, and how it really changed the Tongan culture. The Tongan culture’s view on women, too. That’s a really big takeaway I’ll take from this conversation.

AA: That’s probably my top takeaway too. And again, I just want to thank you for being here and talking about your experience and even the words that were familiar to you and just bringing this home for me. And it was just a joy to spend time with you, too.

ML: Yeah, thank you so much, Amy. This was a really great platform for me to talk about my culture and see how it’s affected me and see how history has affected my culture. Now I get to see how this history is affecting my own view of my culture. So thank you for letting me embrace my culture in this way.

AA: Thank you.

men bowed down on the ground

to certain women.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!