“the same people that benefit from caste oppression also benefit from racial oppression and gender inequity”

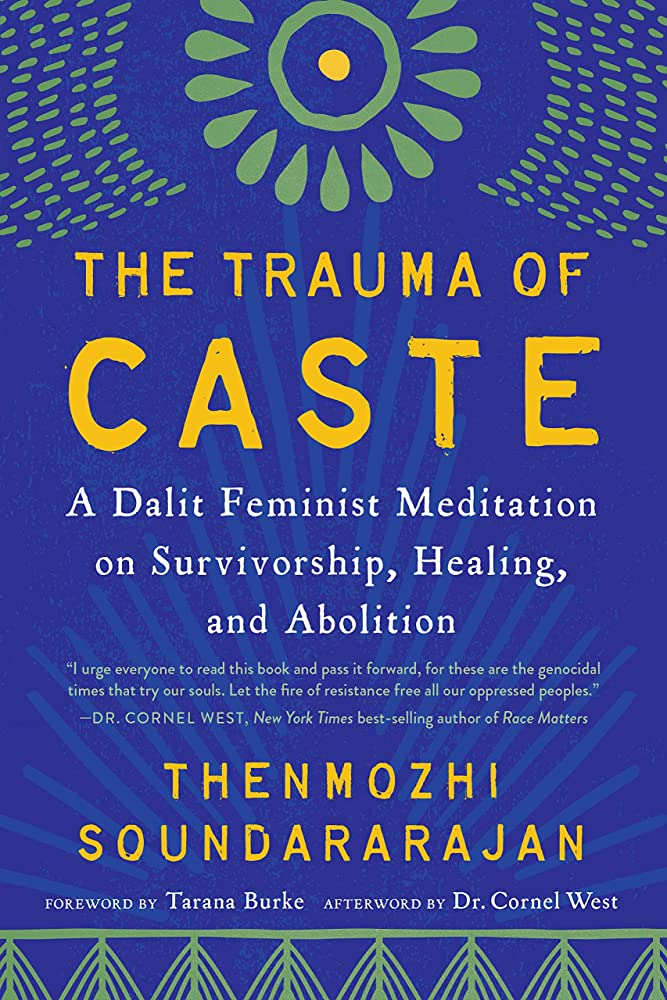

Amy is joined by Thenmozhi Soundararajan to discuss her book The Trauma of Caste: A Dalit Feminist Meditation on Survivorship, Healing, and Abolition and help open our eyes to the oppressive and far-reaching ramifications of the caste system.

Our Guest

Thenmozhi Soundararajan

Thenmozhi Soundararajan is a Dalit Civil rights artist, organizer, and theorist who has worked with hundreds of organizations to better understand the urgent issues of racial, caste, and gender equity. Working across disciplines she is an innovative strategist and thinker that has built bridges between many communities around the world.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Last week on the podcast, we began a series on the country of India, learning about Hinduism, and specifically the powerful female archetypes found in Hindu goddesses. This week we’ll continue our exploration of the Asian subcontinent, shifting our focus to the caste system and its intersections with patriarchy. Several months ago, I was searching online for a book that could address this intersection, and I found the title, The Trauma of Cast: A Dalit Feminist Meditation on Survivorship, Healing and Abolition. I was really intrigued and excited about this title, but the book hadn’t come out yet, so I pre-ordered it. And I read it the day it came out, I couldn’t put it down, and I strongly recommend that listeners read or listen to this book immediately.

I thought it was one of the most important books I’ve ever read, and I want to start today’s episode with a quote from the author, Thenmozhi Soundararajan. She says: “I write this book because progressive Americans of all ethnicities and faiths need to know that justice and dignity and liberation are not just about the issues at home, but about how we build solidarity across nations.”

I think that quote could be the theme of this entire season of the podcast, but I specifically want to invite listeners today as we approach this subject of the caste system, let’s do this in a spirit of solidarity and also with a commitment to take action to show that solidarity. So without further ado, I am so honored to introduce our guest today, the author of The Trauma of Caste, Thenmozhi Soundararajan. Welcome, Thenmozhi, to the podcast!

Thenmozhi Soundararajan: Oh, I’m so glad to be here, and thank you for having me!

AA: Thank you so much for coming. I want to start out with a very brief bio that I got on your webpage, which is far too modest, Thenmozhi. So, I’ll ask you to introduce yourself in more detail, but just for listeners, Thenmozhi Soundararajan is a Dalit American commentator on religion, race, caste, gender, technology, and justice. She is the executive director of Equality Labs and the author of The Trauma of Caste, which as I said is the book that we’re going to focus our discussion on today. So, could you start us off, Thenmozhi, with just a little bit more of a personal bio, where you’re from and what led you to do the work that you’re doing today?

TS: Sure. So, I was born in East LA, and a South Asian American who grew up, just like other immigrants, really thinking a lot about how my family was going to make our way in this world, and dealt with a lot of racism and also dealt with a lot of casteism. And I think that experiencing that as a woman of color really set me on a path to trying to find ways to heal our communities of both. So, as someone who works in a lot of different disciplines, I’ve really tried to work in my career to build caste and racial and gender equity in the fields of technology, in the fields of art, and in the fields of social justice. Your readers may have come upon my work in any one of those realms of advocacy.

And at the heart of all of this, I just feel that sometimes our revolutionary imagination is limited by the people in power who tell us that it’s not possible to live without violence and to not find our best paths as feminists. And I think I was just someone who always like, that is unacceptable, and I am here to live my best life, and I want the people I care about to live their best lives. And so, I found through both organizing, and making art, and also through somatic practice, found a great opening to build the world that we want today as opposed to waiting for it in the future.

So my work is a lifetime commitment to freeing us from these systems of violence and also encouraging us to be able to build the alternatives so that we’re not just fighting a battle, we’re dreaming and we’re architects of the future world that we want.

AA: I love that. And that really came through in the book. I thought the book did a really brilliant job of sharing personal experience and sharing data, and then also not leaving the reader with just a depressed sense of like, this is awful. Though it did include that because that’s completely appropriate, but also saying, what are we going to do about it? And giving people action items of what they can do on a personal level and a communal and social level.

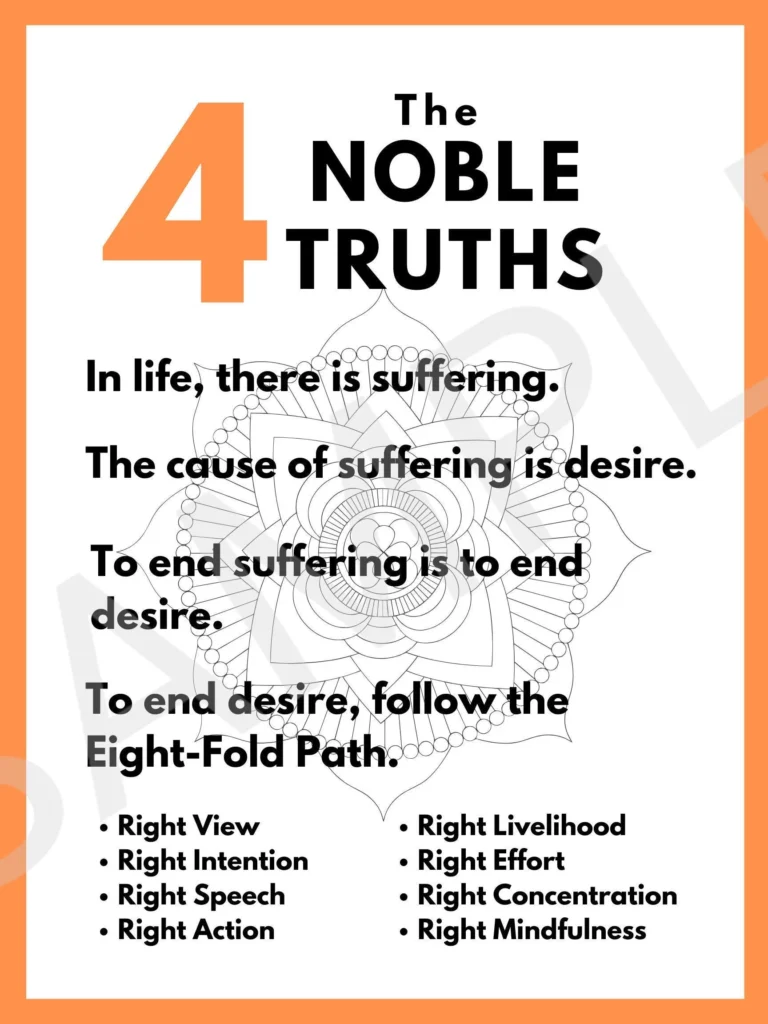

So, I want to start out by introducing the structure of the book, and we’ll structure our conversation the same way. You set up the book with four meditations as a mirror of the four noble truths found in Buddhism. Can you tell us what these four meditations are and then we’ll structure our conversation the same way?

TS: Well, for me, the structure of the book was really about walking people through a process of how to understand a very vast system of exclusion, especially one like caste, which impacts over 1.9 billion people, but we never talk about it. Even though one in four people in the world are impacted by a caste system, and there’s so much gaslighting and there is such a deep taboo about talking about caste, it’s almost like I wanted people to be able to slowly descend into thinking about how large of a problem it is, but also that there are pathways to healing.

So, in using the four Noble Truths of Buddhism, I kind of loosely interpreted those truths to kind of look at, one, thinking about the fact that caste exists, which is one of the first meditations. And then looking at how it impacts us interpersonally and structurally, which is meditations two and three. And then four, how do we then really move to addressing it, and also the urgency of why we need to address it. And I think that when you follow that path, it really gives people enough time to read the book on many levels. Because this isn’t a book that you can just read like in a cerebral way. It’s not like, “oh, I’m just going to read it, knock it out, and then get it done.” It’s like many books around trauma, you need to read it with your body, you need to read it with your heart, and you need to read it with your mind.

And it takes some time to integrate some of the lessons, because like a prism, you can read it through very different lenses. Like if you’re someone who’s really interested in survivor power, you can read it as a survivor and think, oh wow, here is another domain of survivorship I didn’t understand. Or if you’re someone who’s South Asian, it’ll have very deep meaning for you because it’s talking about taboos and conversations we never get to openly talk about. So that’s another piece that might create deep opening. And I think also in terms of feminist practice, there’s a lot about how this book connects to global feminism that is very intriguing. Because oftentimes, especially if you grow up in North America, our understanding of feminism is so shaped by North American context, especially that of the North American racial context. But you know, as you see when you read this book, intersectionality in a global way really needs to be driven by the regional conversation and the regional structures of violence, because it’s not one-size-fits-all when it comes to intersectionality.

So that arc of the four meditations is really to give people pacing and time to really sit with, “oh my God, this system really did this to someone on an internalized level.” Or “wow, I had no idea that the data was so bad.” And even the dimensionalities of how one thing which is very unique about the caste system is that it’s rooted in religious practice. And that has very deep painful implications, because for people who are survivors of religious abuse, because caste-oppressed people are some of the first survivors of religious oppression. And so, there’s an understanding that comes from that that takes time to absorb. So, for me, the pathway of those four truths also was my own journey of freeing myself and healing myself from caste as well.

AA: Well, let’s dive in and talk, as you said about the first meditation, which says that the first truth is that caste exists. And you write in the book, “It exists in the homelands of South Asia and across the diaspora, everywhere South Asians go, causing untold suffering. The taboo of cast must be broken.” So I guess a good place to start, Thenmozhi, would be to define and describe the caste system because some listeners might not really be aware of it. Could you just give us kind of a basic orientation to what the caste system is?

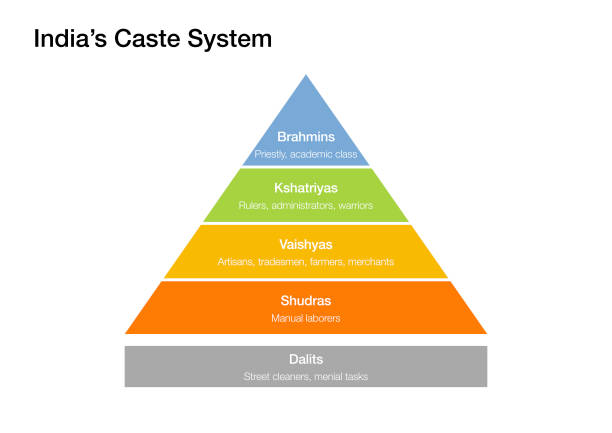

TS: Sure. The caste system is one of the oldest systems of exclusion in the world. It impacts over 1.9 billion people and over 5.4 million South Asian Americans in the United States. And it is a system analogous but not the same as race, and has its roots in 2000 BCE in Hindu scripture. And I think that’s part of the thing that’s probably very hard for people to really understand, is that there’s a religious foundation for excluding people in these very heinous ways that comes out of caste. Because what happens is that you’re born into a caste and that determines the whole of your life: who you marry, where you live, and your spiritual purity, and therefore your profession.

So, the structure of the caste pyramid is that it was started by people who were from the Brahmin or priestly caste, and then they divided the rest of society into different professions and different rates of spiritual purity. So under the Brahmins comes the rulers, who are the Kshatriyas, there’s the merchants who were the Vaishyas, the Shudras, who were the peasants. And then outside of all of that were the people who were Untouchable, which is my community. And we were seen as untouchable because we were seen as spiritually defiling before God, and therefore deserved backbreaking labor and disgusting professions like cleaning up the shit of other communities. And it led to unspeakable amounts of exclusion and violence.

And the heartbreaking thing about all of this is that it’s a social fiction. Nobody gets to determine anyone’s right towards God. But you know, it’s taken a tremendous amount of resources and fortitude and feminist vision to fight this system because people do not, dominant-caste people do not want to be confronted about how much pain this system has really caused caste-oppressed people. So, part of the journey around this work has really been about being unapologetic about how violent the caste system has been. And also, to really be able to ask and demand for the world to understand how significant this violence was and to also ask for healing. Because again, we’re never allowed to even heal from the tremendous amounts of discrimination and violence we face, because to do so would mean we have to acknowledge that there are people who are benefiting from it, and they don’t want to talk about the fact they’re benefiting off of our exploitation. It’s really a lot to be able to speak our truth around this.

AA: Could you share some of the rules for members of the Dalit caste. One, as you said, they’re confined to the most disgusting jobs. And one of the things that I had never known – well, there was so much that I didn’t know – but one thing that really stood out to me that I told my kids after I read it was that Dalits are not allowed to speak, read, or even hear Sanskrit. I mean, Sanskrit is literally the language in which the laws that determine your fate are written, and they had no access to language. And that really struck me, too. Could you talk about that and about some of the other rules that govern the lives of Dalit people?

TS: Yes. Well, it’s interesting because another term for the caste system that we use is “caste apartheid” because it really operates like an apartheid system. We have separate places of worship, separate parts of towns and areas that we’re supposed to live, and we’re not even allowed to be served food and water on the same plates as dominant-caste people. Because to touch us, to share food with us, is to be polluted. That’s how shunned and punished we were.

what happens is that you’re born into a caste and that determines the whole of your life: who you marry, where you live, and your spiritual purity

And the thing about religious abuse, which I just really want to underscore for people is that because this system was set up by priests, and they wrote their laws and their edicts in scriptures, it’s a tremendous thing to think about what it means to conceptualize your conditions of violence. Because you’re not just organizing against social structure, you’re being told that if you step out of line, you’re breaking the order of the cosmos. So it’s a tremendous kind of cluster**** of the mind to fight for your dignity because you’re literally fighting against their notions of God and spirituality.

And some of the first scriptures that established caste, they had these very, very violent edicts where, first of all, all of this language that was determining and writing the laws of castes were written in the language of Sanskrit. And Sanskrit was only allowed to be spoken to, listened to and written by, by the upper castes. So, imagine if you were living in an apartheid state where you had these very punitive laws, but you couldn’t even read the frameworks of your oppression. That’s how virulent this violent system was in its origin. And of course, now it’s spread to many different communities of practice because it’s such a deep foundation for the subcontinent, but I think that lingering violence of being able to not speak to and learn about the terrain of our exploitation, it’s just a deep part of the caste soul wound.

And it’s one of the reasons why I became a spiritual seeker. It was not enough for me to be told “you can’t,” I wanted to know on my own terms who could I be in the divine and what path of the divine existed for me as a caste-oppressed or Dalit woman. And so that’s part of my feminist practice, is to really democratize the access to divine because of how painful this religious wound really was.

AA: If I can really quickly read some of the data that you include in your book as well, just to flesh this out for listeners a little bit. There’s a report that you quote that you say paints an even grimmer picture of the social and economic conditions than people think. The report says that 37% of Dalits live below poverty level, and more than half of Dalit children suffer from undernourishment. And this has led to 83 of every 1,000 Dalit children dying before their first birthday. Additionally, 45% of Dalits do not know how to read and write. One third of Dalit households do not have basic facilities. Public health workers refuse to visit Dalit homes in 33% of villages. Dalits are prevented from entering police stations, it’s just crushing to read it, in 28% of villages. Just thinking, listeners, about what that would mean if you aren’t served by public works and you can’t go to a police station if you have something like crime and violence happen to you.

To continue a bit, Dalit children have to sit separately while eating in 38% of government schools. Dalits do not get mail delivered to their homes in 24% of villages. Dalits are denied access to water sources in 48% of villages, that’s half. And it goes on and on. I actually have to read this other part too, when you talk about sexual violence, which we’ll get to in more depth. But the report showed that 67% of Dalit women have experienced sexual violence, and the average age of death for Dalit women is 39. And I’m just kind of speechless. Could you comment on that a little bit, Thenmozhi?

TS: Well, it was heartbreaking for me to consolidate all of that data all at once. Because as an advocate you might know one or two pieces of these data, and you kind of use them for when you’re talking about a specific incident. But to put it all together, it just paints a picture of exploitation and deprivation that’s tremendous for the mind to hold. And it’s one of the reasons why in that section I just ask people to sit with the numbers a little bit. Oftentimes when we get stats, we kind of raced through the numbers because our mind can’t really hold how staggering the consequences are to systems of exclusion that operate as unchecked as caste does.

And I think also for me, that 39 year statistic of the average age of mortality, that really hit home for me because that’s around my age. And I just thought about the fact of how many other of my Dalit sisters were not going to make what is such a young age for people to be dying. And I think that for folks in North America, this is why it’s so interesting to think about how South Asian Americans really operate here. Because even though we’re racialized as South Asians, once we come to the United States, we are bringing all this trauma from caste, from our other historical genocides and tensions related to language and religion and cultural norms. And we all get kind of homogenized into this category, but we’re actually deeply in conflict and deeply wounded. And as a result, we recreate some of those dynamics here, and one of those painful dynamics is that of caste.

In addition to all of the statistics you shared about caste in South Asia, caste-oppressed Americans have some of the highest rates of discrimination and exclusion in the United States. Amongst caste-oppressed Americans, we have 1 in 4 who have faced physical and verbal assault, 1 in 3 discrimination in educational environments, and 2 out of 3 experience seeing workplace discrimination. And those are not statistics that are about people’s experiences in South Asia, that’s right here in the United States.

It’s part of the reason why I use the lens of trauma to understand caste, because I think that many BIPOC therapists and sociologists and social workers understand that when systems of exclusion are not dealt with at a political and economic level, those communities carry those wounds in very surprising ways, recreating structures of violence in their networks of kinship and in the institutions that they build. And that’s exactly what we saw with caste in the United States because there’s no reason for it to exist here, and yet it’s here in our workplaces. We have employers that are sexually exploiting young Dalit women to be their sex slaves. We have organizations like Cisco who are being sued by the state of California for creating a casteist workplace. And religious institutions like the BAPS Temple Institution, which basically trafficked workers to work for a dollar an hour, according to the allegations of their workers who are in a long Weco suit for their employment practices.

It’s turning into something that is very– it’s not something that we can just relegate to South Asia. Caste as a global problem, and it needs to be treated as a human rights crisis, and it has so many gender-based frames to this issue that for anyone who is a global feminist, we need to understand caste as part of the systems that we’re working to dismantle for our collective freedom.

AA: I have to say that was something that really mind blowing for me, I grew up in Seattle and Denver and then I spent 15 years in the Bay Area, and I’ve had Indian-American friends my whole life, lots of South Asian friends throughout my life, and never ever was I aware that caste was an issue for them living here. And one of the things that you write about in ‘The Diaspora’ is that, you’ll have to correct me if I misunderstood this, but that you can sometimes tell a person’s caste by their last name and also by their religion. And many Christian people who are of Indian descent are typically Dalit. And I have had Christian Indian friends and I looked up the last name and I thought, oh my gosh, I wonder if they were dealing with this aspect of their lives that I was completely oblivious to. And it was really emotional for me actually to think of dear friends that I’ve had, that probably had a lot of inner pain that I just wasn’t aware of as their friend. And so I was really, really grateful Thenmozhi, for having my eyes opened. And I just wish I had known about it when I was younger.

One question that I wanted to ask you, that I wanted you to highlight, that you talk about in the book is how you first became aware of caste. Like you said, you were born in LA and as the child of immigrants who had come from India. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

TS: Sure. And I just want to really take a moment to acknowledge the grief that you had when you were reading about this in my book and thinking about your friends. And it’s an appropriate response. Because I think with the South Asian community, we have needed a reckoning around caste for a very long time. It’s our biggest wound and there’s such deep taboos about talking about it. For some people, they lack the language. For others, they’re just terrified about what it means to be outed. And for others it’s shameful to consider what ways their communities and their family networks may have been complicit with the oppression of other people. And all of that creates the conditions to keep it under wraps and never to talk about it. But as we know around survivorship in other domains, wounds do not heal when they are hidden. They only get healed when they’re tended to, and that means lifting them up and letting it see the sunlight, and slowly beginning to collectively care and nurture it.

And so, I can’t speak to the caste of your friends, but I know that there is no South Asian that isn’t touched by caste in the United States. And a lot of times people have to really work to understand their lineage better, because it’s been sublimated under so many layers of denial and pain and shame and fear. And in my own experience, I definitely saw my parents as two people who were very traumatized by caste. I didn’t have language for it, but as a child you pick up on so many things non-verbally. And my parents had nightmares, they were living their lives in the closet, so they never wanted to be found out and did a lot of things to be hidden.

And I also think they had deep pain about what they’d witnessed and seen back at home but didn’t have language for it. Because it’s not like there were culturally competent therapists around the issue of caste, and certainly even getting therapeutic support for something like this was unheard of at that time. But as I saw it, and especially when I experienced untouchability from the parents of peers of mine, I knew that this was wrong, and I wanted answers. And so I just kept asking questions and it drove my intellectual pursuits at college. And even though I was initially rejected by members of the South Asian faculty, I found a lot of support from other BIPOC feminists there and got my wings especially as I got more and more confident about my experience, met more and more of my community who supported my work. And after I came out, that was this watershed moment because I was one of the first Dalits who was out in the United States, and it just opened up so many conversations. And that’s been the process of my work. Especially in the establishment of my organization, Equality Labs, which is one of the largest Dalit civil rights organizations that is Dalit feminist driven and co-founded. And that work has its roots in that powerful process of coming out and creating a safe space for our community all around the world.

It’s been an incredible journey, but what I’ve seen across the board is how much our stories heal us and that there is a rightness and a power in owning our truth in the face of generational pain. And I can’t say that it’s always easy, because there’s a lot of gaslighting and death threats and rape threats and all of that, but it’s always illuminating. And so much of the terrain of liberation and freedom is the ability for us to understand the human experience farther than the limits of the ego and farther than the limits of these systems of exclusion that would keep us from each other. So, the more that I’ve been able to be rooted in my truth, and rooted in story, I found the more that I’m able to connect to the limitlessness of human experience.

AA: That’s beautiful. I wonder if you would be willing to share a story, Thenmozhi, and one that comes to mind when you mentioned experiencing untouchability by parents of your friends. Again, I was just so struck. And that might be one of the anecdotes, the scenes that will be seared into my mind forever. And I think, like you said, that these personal stories are so important to share because people can be gaslit into thinking you’re just making it up or you’re being overly sensitive. And telling what actually happened and what it feels like in real time is a really powerful way to combat that. So, I wondered if you could talk about the story of when you went over to your friend’s house, and I think your parents had told you not to talk about caste, but you did. And what happened?

there is a rightness and a power in owning our truth in the face of generational pain

TS: It’s funny because I think that when you’re a child, you’re so open. And actually the conditions that were set up around this was that my mom had just had the talk with me about being Dalit. And it’s kind of strange, like when you first read about the caste system, the idea of being a Dalit is that actually you did something bad in another life, and therefore you deserve this punishment in this life. So, I was really obsessed with that, I was a spiritual criminal of some sort. And so, I would stay up late at night and I would ask God, and people forget that children are actually very spiritual beings, but I was a little spiritual weirdo for sure. I loved talking to God. And I would pray to him in all these different places, like when I’d be in the park, like I just loved God. I don’t know if other people had that experience as a child, but it was so natural for me to be connected to my divinity. It was like I was this little magical witchy little girl. But I would sit and talk to God. I’d be like, “What did I do? Was I a rapist? Was I a thief? Was I a murderer?” And I was like, did this only pertain to India? Did it also mean that it was happening here in Orange County too? I just wanted specifics because the whole thing was hard to manage and think about. And so, as I was in this journey of exploration and thinking, I would read everything, and I’d want to talk to people about it. So I was telling everybody that I was Dalit, like I told the cashier!

AA: Oh gosh.

TS: Do you know what I mean? Because it was like, other people talk about their identity. Like, oh, I’m Chinese-American, or I’m actually a refugee. It’s a natural thing to want to say “I am from this community” and it didn’t feel bad because my parents were not trying to make me feel bad in me learning about it, they were just telling me like it was a factual thing. And it was bad that people refer to us as untouchable, but that it’s a fact. It wasn’t something to be ashamed of, they were not ashamed, for sure.

But when I shared this with someone that was Indian who was from an upper caste, I just casually brought it out while their mom was making a snack for us. And as soon as I said it, she didn’t have to say anything. It wasn’t like, “oh, you’re this? I’m gonna do that.” It was like, you can see a non-verbal cue where all of a sudden, a wall comes down. And she immediately changed the things we were served on because she didn’t want me to use their proper plates. And it was very noticeable, and it made me feel uncomfortable. It was done in a way where I automatically understood something was weird, but I didn’t know what. And I thought a lot about it, and when I brought it up to my mom afterwards, she knew exactly what it was. Because she’s lived her whole life watching dominant caste people do those kinds of things. And it was clear that no, it was not to be done.

And as a child that lingered with me. And I think a lot of Dalit children, when they grow up they struggle with feelings of inferiority, and feeling like they’re always a little bit dirtier than other people because of the kinds of ways that the caste system says that we’re dirty and polluting. And we really have to love ourselves beyond these messages that try to dehumanize us. And it’s hard, but I think that journey of loving and coming back into myself was very profound. And in doing that work as a feminist practice for myself I realized how widespread this was for many caste-oppressed and religious minority people. And it’s part of the reason I wrote this book, was I think being acknowledged that you’re not alone and that it’s a systemic problem really gives you ease in your own healing journey, and empathetic witness is such a key part of that.

AA: I’d like to dig in a little bit on Meditation Two. Meditation Two says, “The second truth is that there is a cause for, a source of caste. Caste is a fiction, a human creation set up to benefit a few at the expense of many based in scripture and the philosophy of brahminism. Caste-privileged people, even outside South Asia in the diaspora, uphold the apartheid that grants them more dignity, freedom, status, and wealth. The invitation is for caste-privileged people to overcome their discomfort, step up, and speak out against caste violence.”

So, there are so many aspects of that that we could talk about, but one thing that I wanted to ask is for you to talk a little bit more about the diaspora. You mentioned Cisco, and in your book you talk about casteism in Silicon Valley, and I wonder if you could talk about that a little bit more, because you’ve done a significant amount of work in that arena.

TS: Absolutely. And one thing for our listeners to know is that this book is one of the first books to talk about caste in the United States, and it provides a really good history to the formation of caste and the formation of the South Asian-American identity. So it’s a really great book for just teaching that component for people. But I also think that outside of the data that I shared, caste is such a significant part of our community’s experience. And really the only way to address this is through policy. Because we’re seeing castes show up in so many American institutions, from universities to workplaces to businesses, and it’s not enough to simply say, “oh, we want to do better.” We have to change policy. And this is why we are in this very big moment of a caste equity civil rights movement, where we are seeing organizations around the country add caste as a protected category given some of the grave problems that we’re seeing, from workers being trafficked to sexual exploitation to slurs and harassment.

These are not just simple, hurt feelings. These are actually civil rights crimes and labor laws violations, which is why we want to be able to really work with other movements to get caste added as a protected category. But I think that the biggest thing that people can really do is create welcoming places for all workers by celebrating things like Dalit History Month. And once you add caste as a protected category, invite speakers from caste-oppressed backgrounds so that people have a better connection with caste-oppressed communities. This is a moment where there is so much that’s in crisis, and I think that when we reconnect to each other and our broader human relationships, we find out that we are the ones we were waiting for all along. And I’ve really been so empowered by this model of solidarity that’s not transactional, but where we see our mutual liberation.

And that’s the biggest piece that I can really leave your listeners with is that, caste insidiously finds its way into many institutions. And when you start to center caste-oppressed people, you find that many of the same people that benefit from caste oppression also benefit from racial oppression and gender inequity. And so you are actually doing yourself a service by standing with Dalit people, as Dalit people have also learned so many things by standing with other communities in struggle. So this is a moment where our global connections can really serve us mutually to build the world that we want.

AA: Under that umbrella of cross-cultural and cross-national solidarity, as we educate ourselves about other places, some tricky things come up. And one of the things that I thought as I was reading the book as a person who’s not of South Asian descent, one thing that is hard for me is I thought, I wonder if it’s possible to separate the caste oppression of Brahminism from Hinduism? And I guess more to the point, I guess anytime we explore another culture and the difficulties of another culture, there’s the risk of then having that take a racist turn, right? And I just worry that there might be people who would say, “oh, well Indians are this way” or “Hindus are bad” because of the caste system and that might add fuel to racism. And I actually know that that’s one thing that you navigate really masterfully, but that must be really difficult because people will accuse you of being anti-Hindu. So how do you tease those things apart?

TS: I really appreciate this question because of how thoughtful it is. And I wanna assure folks that the discussion of caste is not harmful to South Asian communities. It is in fact something that brings up discomfort, but discomfort is not the same as harm. And you can think about how difficult it was to have conversations about racial equity, particularly before George Floyd. It really was shaped by the person or organization’s fragility and ability to hold racial stress sufficiently enough to allow for discomfort to be the doorway for greater illumination and reconciliation related to racial bias and discrimination.

And so I think the same exists for caste. And it helps, I think, to separate out the conversation around caste equity from the question of religious reform, because I think those are two very different things. Certainly while caste had its origin in Hindu scripture, it is now found in all communities of religious practice. So I think it’s not a useful practice to say, oh my gosh, is this about one religion? It’s actually found in all religions at this point. So, let’s kind of table that secondary question about religion and just look at caste as a human rights crisis that it is. And we know how to solve the human rights crisis. We use laws, and policy, and DEI trainings and workshops to be able to address them. And that’s what we have to do right now. We have to add caste as a protected category, break the silence around this, and bring in caste-oppressed speakers to help connect and engage our communities in very meaningful and thoughtful ways around this issue, and build power in a way that is thoughtful and kind that brings all of our movements together.

Doing those things is not harmful to the South Asian community. Supporting the South Asian community in a time of reckoning and truth telling, is incredibly nurturing and supportive. And some of the ways I would maybe ask allies to show up is I wouldn’t maybe ask someone what their caste background is, but doing things from a policy perspective like, again, adding caste as a protected category, inviting thoughtful speakers to help gently open this conversation in your institution or org. Reading up great books about caste, like The Trauma of Caste and gifting it and reading it in community with people. This all sends out signals that you are a safe space and a sanctuary for South Asians to discuss caste and to be able to have a political home to discuss this. And sometimes, you might find that a South Asian that you’ve been working with for a long time has been carrying the burden of being cast-oppressed and they open up to you, which is incredible. You might also sometimes find someone who you didn’t know carried some level of caste bigotry, and that’s also okay. Because in many ways, until people who are bigoted or discriminatory understand that the norms around them are changing around caste equity, they can continue to be bigoted without accountability.

And I’m not saying they need to be called out, but sending firm and gentle feminist practices around the fact that there is no compromise around caste equity really opens up people to the place of confronting their own caste stress for the first time, and also sees them to be able to support engaging with discomfort that comes from caste stress. Because too often the caste-oppressed are the ones that carry the burden of addressing the system and carry the majority of caste stress. And that’s what I really want us to be able to move away from. So it is an incredible moment where we are seeing people all around the world speak up on the issue of caste. And I believe it’s towards healing. This isn’t about recreating cycles of violence and harm, it’s about healing and the integration back to the human experience, to each other. Because sure, someone may lose their privilege, but in losing their privilege they gain their humanity, and I think that’s a tremendous thing. 42:30

AA: Thank you so much for that. That actually was a really helpful answer to my question, so thank you. Okay, I wanna talk about one specific, I wish we had more time to talk about each of these meditations, but I’m gonna read Meditation Three and then we’ll dive in on just one of these topics. Meditation Three says, “The third truth is that there are paths toward freedom in each facet of caste violence, carceral culture and slavery, sexual harms, suicide and murder, climate and environmental destruction, cyber hatred, and the theft of the imagination.” And as I said, I mean, I just wish we had a whole separate hour to dig into each one of those things. And I learned so much, so listeners, please do get this book. But I do want to dig in a little bit on sexual harms. So if we can, I’d like to focus now on the intersection of caste and patriarchy. Could you do that, Thenmozhi?

TS: Sure. So for feminists that are listening, you may be really used to people talking about white heteropatriarchy or even cis heteropatriarchy, referring to patriarchy and the intersections around gendered ideas of domination. But in the South Asian context, for us white supremacy is not the dominating ideology that frames our ideas of gender, it’s caste. And so that’s why we use the term brahminical patriarchy to refer to intersectional understandings of caste and gender. And brahminical refers to, again as we go back to the caste system, that first caste that established everything were the brahmins, the priests. So we use the term brahminical to refer to the animating ideology that undergirds the caste system.

And so brahminical patriarchy is really the way we understand how caste and gender are intrinsically linked. And this is because one’s caste is determined by the family that you’re born into. It’s literally from your family line. So as a result, there is a lot of control of the reproductive function of all genders because that determines the purity of your caste line. And so all of the norms related to gender control and gender-based violence have their roots in caste. So, for dominant caste cis women, they are very highly controlled, there’s a lot of like, kvetching about their honor because if they sleep around or break their purity, they actually damage their entire lineage in terms of the purity of their caste families.

And for caste-oppressed women and Dalit women, they are seen as consistently impure and also easily accessible for gender-based violence. And in fact, Dalit women’s bodies are a primary way that caste gets enforced across the system because there’s a whole pattern of gender-based violence crimes, and we call it caste-based sexual violence that is done to humiliate a Dalit woman and also to dishonor the Dalit community. And this includes the shaving of hair, the stripping of people publicly, tarring people, and of course rape and murder. So it’s a very heinous system and it’s one of the reasons why I spoke up about this as a survivor of gender-based violence, and also knowing how deeply hurt our sisters were from this violence. And so, a lot of times when we talk about ending rape in the South Asian context, you have to end caste. Because there’s so much impunity related to Dalit rape that comes at the hands of dominant caste people. And this is the need of the hour. And it’s why I think when people are looking for global partners around feminists in South Asia, they have to center Dalit women because of how much pain and suffering we’ve gone through.

AA: Tell us the story of #smashbrahminicalpatriarchy.

TS: Well, this was such an interesting story for your listeners because essentially I had collaborated on a series of posters that talked about different aspects of the work that we do at Equality Labs. One said “End Caste Apartheid”, the other said “Smash Brahminical Patriarchy”, which is essentially saying smash the intersectional form of gender oppression in our context. And the other one said, I think something like “End Islamophobia”. So I had sent a bunch of those posters to India with different friends and colleagues, they were really popular. And it just so happened that one of those colleagues was meeting with Twitter to talk about the safety of women on the platform with a bunch of other women journalists and activists and human rights defenders.

And in the resulting meeting that came from that conversation, Jack Dorsey of Twitter posed with one of my posters. And then it was leaked to the public and that caused this entire hullabaloo where basically dominant-caste Twitter melted down because they saw the head of a major social media company talking about caste and gender. And Jack didn’t know what he was holding, frankly, he just held it up because someone who was talking about how they’ve been de-platformed because of castes and misogynist content shared this out of an authentic place of solidarity and relationship building. And the response was basically for a day Jack had this experience of what it was like to be a Dalit woman on Twitter. Because there were all sorts of bigoted comments, there were calls for him to be arrested, and lots and lots and lots of gaslighting around. But also what happened was that the global feminist community really responded. And there were women’s movements from around the world that put this conversation front page on global newspapers everywhere.

And so all of a sudden, this little piece of art landed a conversation about caste and gender in The Guardian, in newspapers in Brazil, and also I was able to write an op-ed in The New York Times about this incident and really broke the conversation even more about castes and gendered hate speech on the platform. So to me, that moment was as much the power of a singular piece of art to open up a conversation, but also the ways that Dalit women have to go through extraordinary means to have our stories of experiences of violence be heard on the global stage. And yet there was so much resilience and strategy and power building that happened in that moment. We took this moment of crisis and attacked and turned it into power.

AA: Amazing. Really, really incredible. Okay, one other question that I wanted to ask you about that falls kind of under the heading of Meditation Three, is the genocide that you refer to in India. And I was really floored when I read that. I thought, how have I never heard about this? And I wonder if our listeners haven’t heard about a genocide in India either. So I wonder if you could tell us about that development.

TS: I so appreciate this question. Thank you so much for this one. And I think it’s really hard when a genocide opens in your context. It’s like everything changes. And I think for Indians, this process, while it had been building, I think really launched at the end of 2019 where there was a passage of an act called the Citizenship Amendment Act. And it created for the first time in Indian history a religious criterion for Indian citizenship. And people that didn’t qualify for the very stringent parameters that were being set, they would be denaturalized and be on the pathway for being put into a camp. And there were earlier camps already in the country in Assam and parts of the Northeast, where another process called the National Registry of Citizens (NRC) had already set up concentration camps, internment camps for people that were denaturalized and seen as not Indian. And there’s already 1 million+ people already in those camps.

So, with the CAA, many viewed this as the nationalization of that process and the opening to the largest network of concentration camps to be built in world history under this administration. And this has really been a Hindu nationalist goal for a long time in their pursuit to try to make India a Hindu nation. And the subcontinent has always been a place with multiple religions and has been interfaith and inter-caste. And so when you see such a large religious ethno-nationalist movement shift the tenor in a country to allow for such mass incarceration, this is the last couple years that we’ve been dealing with. So we’ve seen the rise of extremely violent, dehumanizing, dangerous speech. We’ve seen mass atrocity, lynchings and many, many political prisoners being thrown into jail for speaking out about what’s happening. And it’s a terrifying moment, particularly because a lot of the animus is against Indian Muslims. And Muslims are a caste-oppressed faith in this context, as are Christians. But we’ve seen the demolition of religious institutions and the abuse and murder of religious leaders.

And I think when you see a culture turn to such polarization, it’s ugly, it’s heartbreaking. And the shocking thing is that very few people are talking about it. Certainly important people in the field of human rights like Gregory Stanton of Genocide Watch, he has called India in a state of open genocide. And there’ve been many different kinds of acts by the US government, like naming India as a country of particular concern because of the religious ethnonationalism that’s occurring. But fundamentally, this is a moment where people of Indian descent have to really decide what they are going to do when genocide is happening right before their eyes. And there is this place before a genocide really begins in earnest, where people have a choice to pivot and turn away from genocide or to be complicit. And I think that’s where we are right now. The pandemic slowed some of these things down, but now that the pandemic is lifting, we are hearing the calls from mass atrocity and the boycotting of Muslims and the removal of Muslims from public life, larger every day. And that drumbeat of genocide is very, very hard to turn away from.

people of Indian descent have to really decide what they are going to do when genocide is happening right before their eyes

But that’s part of why I wanted to really encourage people to think about another path towards reconciliation, because it’s much harder to do these processes after camps are built, after mass murder has occurred. As much as there is a fervent desire to fall over that cliff and embrace the darkest parts of ourselves and surrender to death, we can also choose life. And to choose life is one of the greatest responsibilities we can have, particularly when we think about what legacy we leave to our children. And so I felt that it was really important to speak about this genocide. And to me, from my perspective, it’s like an act of brahminism, or the caste system on steroids, to dehumanize millions, to justify putting them in camps. And we have to do better.

And that’s part of why I wrote the book in the way that I did, was I wanted to give people a chance to be people of courage, to be people who could stand with the light in that time of darkness. Because I read many, many accounts of genocide. Particularly the ones that occurred in South Asia, and that might also be new for your audience to think about, is that even though people have this romantic version of the subcontinent as the place where people go to get enlightenment, like The Beatles and Steve Jobs. People want to eat, pray, and love their way to Nirvana. But in actuality, we’re lost just like everybody else. And we have so many genocides that have occurred because of religious and caste tension in our context. And I think that because we are not self-examining the causes of that, because we’re not actually healing and dealing with the reconciliation that requires from those previous ruptures of violence, we are setting the stage for us to fall even deeper into what would be, if this genocide continues, it would be one of the world’s largest genocides in world history. So we have to do everything that we can to turn away from that and to choose life. And that’s why I wrote this book in part. I wanted to help equip people to find different tools for this.

AA: I’m so grateful that you did, because like I said, this was completely new to me. I mean, I’ve read about President Modi in a few articles here and there and just kind of hearing rumblings like, oh, that does not sound good. It sounds like echoes of divisions like that, that I’ve read about from the time of Partition when there was just open genocide, there was warfare. But I had no idea the scale and the scope of it. And I’m just really stunned at how little we are hearing, at least in my newsfeed, I’m just not hearing about it. So, listeners, this is something really to look into and we’ll come back to this in just a couple of minutes at the end of the episode about action items, things that we can do.

But I did want to quickly also talk about Meditation Four, actually this is a good segue to Meditation Four, which is our final topic. The book says: “The fourth truth is that there can be an end to caste. The end lives in sacred connections with other oppressed peoples. The end is seeded in the resistance of caste reformers and abolitionists. The end exists within the power of survivors.”

So I wanted to ask you, Thenmozhi, about some ways that people are fighting back. And if you do have some action items, a call to action for listeners of what we can do to act on these feelings of solidarity.

TS: Well, I think one of the things, and you touched upon it in what you said, is that the book makes a very strong case that solidarity is not transactional. It’s about our mutual freedom. And what I have learned in being in community with many other movements is that you have to really learn of that movement before you can carry its water. So I do really think that the first step for many of your listeners will be not only just listening to this conversation, but buying this book and reading it in beloved communities so that you can learn and think through some of those ideas. Because the book is not just meant to be read. There’s worksheets and there’s meditations. So there’s a lot of community building processes that I think can come out of that.

Additionally, I really recommend that people get connected to Dalit people. And it could start with signing up for the mailing list of Equality Labs or another Dalit civil rights organization that might operate in your neighborhood. I would also ask folks to be really strong allies and work with your HR department and add caste as a protected category in your organization. In a lot of ways, because caste-oppressed workers face so many discriminatory experiences when they work in their institutions, we really need to figure out ways that we can make all our workplaces safe for all workers. And it starts with adding caste as a protected category, doing trainings to build caste equity so people are more competent about the issues of caste bias in their institutions. Also consider celebrating Dalit History Month and having Dalit leaders or speakers to come and speak at your organization or events.

And if people are like yoga practitioners or part of some sort of dharmic religious practice, I would also consider opening up a way to have some sort of caste equity acknowledgement at the opening of your sessions. Because a lot of people do land acknowledgements already and they also acknowledge what happened in terms of enslavement for us here on this land base. And I think when you practice a dharmic tradition, you also have to honor the violence that occurred in those practices. And something very simple could be: “We derive benefit and enjoy the community that we’ve built around this. And we also acknowledge that millions of caste-oppressed people were harmed in the formation of this tradition. And we honor them and that legacy of pain and will work side by side for their freedom.” Something as simple as that could be so transformative. And I think for all the feminists and people that are thinking about how to build power around the lens of gender, I think it’s so important that we recognize that there are so many different types of feminism, especially once we get outside of our North American context.

And to think about Dalit women, to bring Dalit feminism into your space where you were thinking about radical gender equitable futures, these are all things big and small that can be really powerful in terms of caste equity and around the genocide in India. I really encourage people to keep reading and keep speaking up about it. Gregory Stanton at Genocide Watch and the Indian American Muslim Council have great reports about what’s happening. You may see action alerts from organizations that are working to try to get the story out about what’s happening. Listen to them and lift up their voices because the world stops genocide, not just one person. And we need everyone to do their part before it’s too late.

AA: Well, to end our conversation today, actually, I’d love you to read a passage from your book, Thenmozhi, on this very topic. We talked about a passage that’s about on page seven of the book that I think is such a powerful, again, a call to action for everyone listening. So if you could just read that passage to finish us off, that would be wonderful.

TA: Sure. It’ll be my honor.

“To heal from the trauma of caste is to free ourselves from all the demons that systems of oppression create. Whether it’s inside of ourselves, whether it’s in the ways that we interact, whether it’s in our engagement with the species, it’s a call to interrogate everything so that we can reimagine what’s possible. This is a call to the world that the time to rise with Dalit people is now. No matter where you’re from and what kind of spiritual practice you may or may not engage in, whether you have any connection to caste apartheid, because the world stood with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and the Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa, these causes succeeded. Now the world must stand with Dalit people to end the violence of caste oppression in the name of all who have suffered from systems of separation, exclusion, and exploitation. We have gone too long without a global empathetic witness to our struggle, and we wish only for a reconnection back to humanity.

The yearning for global empathy is something I feel deeply in my body. At times, I find my breath caught in my chest, for I know this is a battle our people will not win alone. Our return to humanity requires a reconnection of material solidarity with all the peoples of the world. It is vital that as many allies from as many traditions as possible lend caste-oppressed people their support, love, and strength. For our survival is linked with your own. Do we have the courage to answer the moral call to action? Or will we sit by afraid of our discomfort, hiding from the wound, nursing it, and letting it fester because it’s terrifying to confront the pain it holds? I’m here to tell you that the avoidance of the wound will lead to consequences far more frightening than if we just work together to confront the pain that sits in our heart, and let the wound be the teacher.”

AA: Well, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, thank you so much. Thank you for reading that passage. And thank you so much, it’s been a real honor to talk with you today.

TS: Oh, absolutely. And the honor is mine, and I look forward to coming back soon, and thank you so much for this really beautiful and wonderful space.

there are so many different types of feminism,

especially once we get outside of our North American context.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!