“our entire world is laboring under white supremacy and it harms all of us”

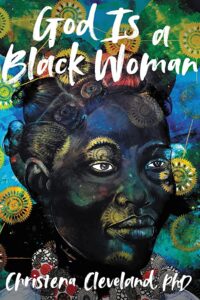

Amy is joined by Dr. Christena Cleveland to discuss her book God is a Black Woman and unpack our assumptions about divinity, gender, and race.

Our Guest

Dr. Christena Cleveland

Christena Cleveland Ph.D. is a social psychologist, public theologian, author, and activist. She is the founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal as well as its sister organization, Sacred Folk, which creates resources to stimulate people’s spiritual imaginations and support their journeys toward liberation.

A weaver of Black liberation and the sacred feminine, Dr. Cleveland integrates psychology, theology, storytelling, and art to stimulate our spiritual imaginations. She recently completed her third full-length book, God is a Black Woman (HarperOne), which details her 400-mile walking pilgrimage across central France in search of ancient Black Madonna statues, and examines the relationship among race, gender, and cultural perceptions of the Divine.

Dr. Cleveland holds a Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of California Santa Barbara as well as an honorary doctorate from the Virginia Theological Seminary. An award-winning researcher and author, Christena is a Ford Foundation Fellow who has held faculty positions at several institutions of higher education — most recently at Duke University’s Divinity School, where she led a research team investigating self-compassion as a buffer to racial stress. Though Dr. Cleveland loves scholarly inquiry, she is also a student of embodied wisdom. She recently completed the Art & Social Change intensive body wisdom training for millennial leaders, and is currently deepening her mind-body-spirit integration in a year-long life practice program for BIPOC.

A bona fide tea snob, lover of Black art, and Ólafur Arnalds superfan — Christena makes her home in Boston.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As a thought experiment, I would like you to picture God. What comes to your mind? My guess is that regardless of your own gender, you picture God as a man. And my guess is that regardless of your race, you picture God as white. An old white man, probably with a beard, maybe with a white robe. And I’d like to start our discussion of the book that we’ll be discussing today with a quote from its pages. “Everywhere we turn, there are pictures of God as a white male in churches, films, and everyday conversation. The prevalence of white male images of God easily leads us to conclude that God is definitively and exclusively white and male. And like many culture-shaping ideas, we don’t even question the idea or how it shapes our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. For most of us, regardless of what we might want to believe or claim to believe, the image that immediately comes to mind when we imagine God is that of a powerful white man who is for and with powerful white men. It’s a deceptive idea that flies under the radar, powerfully shaping us without our consent.” Today we’ll be discussing the book God is a Black Woman by Dr. Christena Cleveland, and I’m thrilled to welcome Dr. Cleveland to the podcast today. Welcome, Christena!

Christena Cleveland: Thank you! It’s so great to be here.

AA: I’m so excited to have this conversation with you. We were just discussing your book actually at the dinner table last night with my husband and my kids, and when I mentioned the title—my husband had seen me reading it but it had been a little while—I said that we’re recording about God is a Black Woman and he just sat there and he said, “Wow, I don’t even realize how it has impacted my psyche to have grown up with a god that looked like me. Because when you say God is a Black woman, my initial response is…No. God is not a Black woman. Why do I think that? Because I think he’s a white man!” Just the title has an impact. It really does. So, I’m grateful for your book and really excited to discuss it.

I’d like to introduce just a little bit of your professional bio, and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself more personally. Dr. Christena Cleveland, PhD is a social psychologist, public theologian, author, and activist. She’s the founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal, as well as its sister organization, Sacred Folk, which creates resources to stimulate people’s spiritual imaginations and support their journeys toward liberation. So again, Christena, so excited to have you! I’m wondering if you can introduce yourself to our listeners a little more personally, tell a little bit about where you’re from and what led you to do the work that you do.

CC: Yeah. Even as you ask those questions at the beginning of this conversation just a few minutes ago, you know, when you picture God, what do you picture first? I’m someone who, like your husband and like so many people, is healing from that image of that scary white man, that distant white man, all powerful. I’m actually back in France in the land of the Madonnas as we speak. And yesterday I took the day off from work and took the train about an hour and a half south of where I am into the Cantal region, which if you’ve ever had French cheese, it’s probably from that region. It’s this beautiful mountainous region, and I hiked about an hour and a half out to this teeny tiny chapel to visit a Black Madonna—an image of God who’s Black and female—because I need to be reminded of this truth: that I’m sacred too, that all of us can be found in the image of God. And so that’s a big part of my work, is healing from the way that I was raised. I was raised in a Black family; I’m African American, my parents are African American. But even in a lot of these Black church spaces, and then also some white church spaces that we were also involved in, the image of God was often this white man, either explicitly or implicitly. Sometimes there was the picture up on the stage or near the pulpit, but sometimes it had more to do with the doctrines of patriarchy and white supremacy, patriarchy’s BFF. Just a lot of linearity, a lot of obsession with certainty and tradition, a lot of hierarchy, and a lot of like implicit and explicit denigration of Black and brown people and of women and non-men.

And so, yeah, I grew up in that! Little ‘80s girl, and started awakening in my early thirties about 10 years ago, and have been on a journey since then that led me here to France. And I started coming here in 2018 to visit these Black Madonnas, these ancient, very uncommon statues of the Virgin Mary. Although, oh, she’s so much more than the Virgin Mary. And the Virgin Mary is so much more than the Virgin Mary. So that’s a whole other conversation! But I started coming here almost five years ago, and I’ve been coming back every year that I could (I couldn’t come in 2020) just because it feeds my soul to see the sacred images of Black women and to connect with the land and the people who have venerated them as sacred. So this is a huge part of my work, that liberation from white patriarchal religious conditioning, but more broadly liberation from white supremacy and how my thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are unconsciously tied to these ideas that are anti-human and hierarchical and preventing me from connecting with myself, and with the earth, and with the divine, with other people. And so it’s a journey and it’s an exploration, and it’s artistic and it’s scientific and… It’s a joy!

AA: That’s awesome. I’m wondering if we could dive in a little bit on that topic. Your book is so great for so many reasons, but one thing that I really enjoyed about it was that I was really able to get inside of your experience, which enabled me to have empathy and really feel what it felt like for you growing up. And I’m wondering if you can take us, take listeners who haven’t read the book yet—and I do recommend that they buy this book and read it—but for those who haven’t read it yet, tell us what it did feel like for you to grow up with that white male god, if there’s an anecdote that you could share.

CC: Sure. I can share one of the first instances, one of my first conscious encounters, maybe semi-conscious because I was like five, with ‘whitemalegod’. That’s what I call him in the book, whitemalegod, all one word, all lower case. I was a five-year-old, just graduated kindergarten and was at vacation Bible school, which is kind of like a summer camp that’s like Sunday school all week. Evangelical white churches tend to run them, at least they did in the ‘80s, and my brother was there with me. We were the only Black kids at the vacation Bible school at this particular church nearby our home. And we were playing tetherball and we were really caught up in the game because we love tetherball, still love it. It’s such a fun childhood memory playing tetherball with my gentle giant of a brother. And we must have missed the teacher’s call to come in from our recess back to the Bible lessons, which is the heart of Vacation Bible school. And I say we must have missed her call because we’re both pretty obedient kids, and the next thing we heard was, “Get in here, you n*ggers.” And we both stopped. And I remember the terror in my bones. I remember the wave of shame that passed through my body. And on a level, I think I stopped breathing. Like on a cellular level I stopped breathing. Because something in my little Black girl body knew that I was not welcome and that I wasn’t safe in that space, even though I didn’t know what that word meant. That was a new vocab word for me.

I need to be reminded of this truth: that I’m sacred too, that all of us can be found in the image of God.

It wasn’t a word that was used in our home, and I hadn’t encountered it yet, and I had to go home and have my mom explain to me why I felt that lack of safety and that shame. And I say that I stopped breathing at that point on a level because it wasn’t until a little over thirty years later, when I first started encountering images of the Black Madonna, years before I even traveled to visit any of them in person, a wave of release came over my body. And it was like the reversal of that first wave of shame that coursed through my body. It took me back to that story. It took me back to that experience as a five-year-old, and I was able to recognize that what that teacher had taught me about God; when I say she taught me about God, because by treating me and my brother that way she taught me who’s sacred and who’s not. And isn’t that what our concept of God is about? Who is sacred and who’s not. And in our culture, white people are sacred and men are sacred. And you see that in whose testimony is valued, and who gets voted into office, and who is seen as leadership potential and material, and whose life matters.

And so I think of that as my first encounter with whitemalegod. And I wish I could say that was the only time I’ve ever experienced whitemalegod in our society, but as I grew up and as I started to see the much more subtle ways that whitemalegod shows up—whitemalegod typically does not show up in a white lady calling you the N word, usually it’s a lot more subtle, it’s a lot more alluring than that. But yeah, it felt like I was constantly on the run from myself and from God. Because I always felt like I had to contort myself into something other than what I was in order to somehow please this God who wanted nothing to do with me, and declared that I was not sacred and not part of the fold. And so, I grew up in Christian churches and got these messages like, “Come boldly before my throne of grace” and “For God so loved the world.” The whole world, supposedly.

So you get these explicit messages, but then you get these implicit ones saying, “actually you don’t really belong and we don’t really value you.” And that rose to the surface for me in a powerful way in 2012, when Trayvon Martin was shot and killed by George Zimmerman. I saw how so many of the white Christians in my world who had called me Sister and called me Beloved, and I had served in their churches, and volunteered for their programs, and babysat for their kids, and donated to their missionary causes… we were supposedly family. And all of a sudden, when there’s finally this national conversation that explicitly shows that Black and white Americans do not see things the same way, do not experience the same world, they refuse to enter into that conversation. They refused to see the humanity in Black people’s experiences. And that was a huge wake-up call for me, because I had devoted a lot of my life to that world and was even teaching in a Christian college at the time. And so not just socially and spiritually, I was vocationally and sort of capitalistically tied to that world. So, yeah, just another example of whitemalegod showing up. You know, these folks are theologically incapable of seeing the divinity in me. They cannot.

AA: I was really gutted reading about that in your book, and there’s a quote that I want to read that was shocking and heartbreaking to me. It’s by Frederick Douglass, and you talk about what you call “Slavery’s White Christ”, and Frederick Douglass wrote this in the 19th century. He wrote,

“For all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. The religion of the South is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes, a justifier of the most appalling barbarity, a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds, and a dark shelter under which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal deeds of slaveholders find the strongest protection.”

As a person who grew up Christian, myself, the incongruity with what I perceived to have been Christ’s message was just really, really distressing on a deep level. And it was so awful to me to read in your book and to hear you talk just now about that deep betrayal, that that kind of racism and hatred would happen in the space where you had hoped to, and I guess assumed, that you would’ve been safest. As part of the family of God. It’s just so awful.

CC: What’s interesting though, is that to me, the deeper betrayal is that white patriarchal conditioning that didn’t allow me to see the betrayal. So rather than looking at this situation and being like, “this isn’t right, the Jesus that I see in the gospel of Mark is nothing like the Jesus on this megachurch pastor’s platform,” right? Even though on some level my body felt that, and I remember specific times in my life growing up as a child and a teenager and a young adult feeling this sense of dread or a lack of safety in these spaces every single time, rather than naming the spaces unsafe, I did what the white patriarchy taught me to do, which is blame a victim. And I named myself as wrong, or unsafe, or heretical. And so I’d been turned on myself and did more to whip myself into shape. “Christena, you need to be more like Christ. You need to turn the other cheek, or you need to stop being so selfish, or you’re just deceived like women are. You need to just repent and submit.” And what was quite jarring was waking up to that. That was the earthquake of all earthquakes! I mean, I can laugh about it in retrospect, but it wasn’t something I was laughing about at the time, I was throwing things. [Laughing]

AA: Well, I wonder if you can talk about that, because you talk in the book about how you grew up in a Black family and grew up going to church. How did that impact your parents?

CC: I’m still not quite sure how it impacted them. I know what was challenging for me, was realizing that white patriarchy doesn’t just exist in white spaces in the same way that patriarchy doesn’t just exist in male spaces. And I think there was a special grief that I had to undergo when I realized that I wasn’t safe from whitemalegod in my own Black home. But that was a really important grief to go through because what that then brought me to was the truth that I’m not safe from whitemalegod in my own thinking. And I talk in the book a bit about how whitemalegod is a shapeshifter. He can kind of move through and inhabit different spaces and institutions and people, and he doesn’t always show up in people that look like Trump. And that’s kind of how he’s effective and maintains the power that he has. So I think that was a very powerful experience. A painful experience, but one that awakened me to the reality of how white patriarchy works. That you can’t exactly just blame one people group, because we’re all susceptible and we’re all affected as humans.

AA: Yeah. I did get that sense in the book that especially your dad, and I do appreciate the sophistication and nuance with which you treat your parents, your dad seemed to have a lot of internalized…

CC: whitemalegod.

AA: Yeah, correct me if I’m wrong, but there’s just that self-loathing that comes from living in a white supremacist society and that he sometimes ended up perpetuating that and actually acting that out on you.

CC: Yeah, yeah. You know, it was so powerful. I wrote about 20,000 words about my dad that didn’t go into the book in his story. Because I really wanted to ground myself in his humanity before I shared the parts that did go into the book. And that was part of the plan, you know, I knew as I was writing those things that they wouldn’t go in the book. Because the book isn’t about him, it’s about me. But I think one of the gifts of starting to heal, I’m still very much on my journey, but starting to heal is wanting to be able to—I think there’s so much about white patriarchy that wants to throw the baby out with the bathwater, and wants to see everything in black and white, and wants to like colonize the moral high road, you know? And I think connecting with what I call the sacred Black feminine has really inspired me to see, you know, here’s this person’s perspective and what has happened to them. The abuse that’s happened to them and how that has been sort of passed on unintentionally. Not to say that there isn’t responsibility needed, but I love that very different way of the feminine, of wanting to hold everything even when it’s not easy to. Yeah, that feels like a miracle to me.

AA: There’s one episode in the book too that I wanted to talk about, and I’m going to kind of get into this episode by reading a quote from the book where you’re talking about maleness. So we’ve talked about race a bit so far in the episode, and I want to kind of take the angle of God being a male god. You write:

“Though masculinity is intrinsically beautiful, it is designed to be an interdependent relationship with femininity. Characteristics that are often associated with masculinity like assertiveness, independence, and agency are healthiest when they are in partnership with characteristics that are often associated with femininity, like emotional expressiveness, interdependence, and nurturing. Like yin and yang, masculinity only works when influenced by femininity. In Christianity, we are left with a male God that is not only masculine, but masculine in a way that crushes femininity. We’re left with a male God that is not at all influenced by femininity.”

And so as I was thinking about this really lopsided God, the question that I have for you and leading into this episode is, what effect does it have on men to worship a male God who has no feminine counterpart within Christianity? And as I’m thinking about toxic masculinity and men who exhibit a lot of sexism, partly just because it’s modeled for them and they’re not even aware sometimes… My question for you is how that impacted you, and I’m particularly thinking of the passage where you were trying to deal with all the trauma in your body by making a list of all of the white men who had oppressed you throughout your life. Could you talk about that?

CC: Yeah, that list is so long. I spent five months creating that list and working through that list because I think there were over 400 names on the list of just people that I could remember. And yeah, when I think of that patriarchy it just shows up in a lot of petulance, a lot of extremely weak men, extremely weak people who can’t handle opinions that are different than their own, can’t be present to uncertainty and pain, don’t know how to empathize. And so a lot of my encounters with these white men were due to my work in the church where I was kind of like a vanguard or a spokesperson of racial reconciliation in the early 2010s. I was speaking all over the country and big conferences and important boardrooms and that sort of stuff within the Christian Church. And I would bring up statistics and data and research and reflections and, you know, perspectives on scripture and would just get clobbered, you know, shooting the messenger.

What strikes me about that is the inability to just be with something that’s uncomfortable, to not even be able to consider it. And I remember in between my first book and this book, God is a Black Woman, I wrote a book called Power Trip, and when my agent and I were shopping it to different publishers we had a few different meetings. And in one of the meetings, the white male publisher was there with several members of his team because they were seriously considering this book, and there were younger members of his team who were women and or people of color who were excited about the book and wanted to offer me a big book deal, but they had to go through their boss. So he was at the meeting too, and he was clearly triggered by my book proposal and so he just came out guns blazing at me. The entire 25-minute meeting was just him cutting me down and cutting my credentials down and cutting my proposal down and all this stuff. And afterwards, my agent called me and said, “In my 17 years as an agent, I have never seen anyone talk to anyone like that before. How are you doing?” And I was like, “Oh, I’m fine, that’s like a Tuesday in my life. This is what I deal with every single day.” Now, not surprisingly, a year later, my digestive system completely shut down because my life was indigestible and I was carrying so much trauma. But that’s just how I was treated every single day.

And so, I think what this whitemalegod does is… whitemalegod is violent, whitemalegod rules with an iron fist, whitemalegod is easily threatened, constantly has to make displays of his power. I share in the book about this sort of Scarlet Letter experience where this young girl was brought before our entire congregation because she had gotten pregnant and she wasn’t married. These displays of power and domination. And so then that’s what people are taught to do, is to be violent in that way. And yeah, it’s really powerful. It goes back to the point that ideas matter. They shape us even if we don’t know that we’re being shaped by them.

Another thing that’s striking too is, like you were saying at the beginning of this conversation, your husband was reminded of the title of the book, and correct me if I’m wrong, but it’s almost like he had a reaction, right? Like “Oh, I feel something in my body when I hear that.” That’s one thing, right? But then to go straight to judgment versus curiosity, which it sounds like your husband went a little bit more towards curiosity, but I think that sort of patriarchal conditioning just goes straight to judgment and shutting it down. Because we all feel things all the time, right, but how do we respond to it? And I mean, I’m an Enneagram One. I don’t know if you know the Enneagram, but I can tend to go towards judgment rather than curiosity too. And it’s been helpful for me to notice that that’s whitemalegod. That’s all that is, and I can release that because that way of relating to the world hasn’t healed anybody ever.

AA: Mhmm. Yeah, that’s right. Noticing those assumptions coming up, or that certainty in dogma and saying, well, that’s not right. And then meeting that thought with, huh, that’s interesting that I responded that way, I wonder what the conditioning is in my own mind and my own body that makes me think that I know that that’s not true, or that I know that that is true, and push and interrogate our assumptions. That’s the goal. I totally agree. I mean, we’ve all received conditioning, we’ve been breathing in the air of our environment, right? But it’s what we do with that once we become aware of it, I think that’s where we can make change and reteach ourselves, hopefully.

So my next questions are going to be about healing after all of this trauma that you really accumulated throughout your life and then had this kind of epiphany. One of the moments that I’d love to start with, that I thought was so beautiful and memorable from the book, was after a complicated and fraught relationship with your own body, which I think a lot of women probably of all races, especially in American culture, can relate to, but especially an African American body in a white supremacist society, the difficult relationship that you had with your own body with binging and restricting and over exercising… But you write this beautiful passage. If you don’t mind, I’m going to read it. I believe you were looking in a mirror and you looked at your own Black female body, and you said,

“She had been with me all along, affirming, sustaining, and supporting me in the form of my own body. Through all of my failed attempts to win validation from whitemalegod and his minions, she had been there all along, keeping me alive and sticking by my side.”

It just makes me choke up even to read it. Can you tell us about that a little bit?

whitemalegod is violent, whitemalegod rules with an iron fist, whitemalegod is easily threatened, constantly has to make displays of his power

CC: Yeah. Oh, thank you for reading that passage. It was wonderful to be reminded of it. Yeah, so one of the things that whitemalegod taught me through society and through religious conditioning was that my body needed to be whipped into shape, that my body was unlovable, and that the only way that I could potentially experience any of the love that’s available to other people is by looking as much like a white girl, a skinny white girl, as possible. And so, I think I first started binging and restricting when I was like six or so all the way through my mid-thirties. I had this really violent relationship to my body and to food, and the process of recovery for me really began with reclaiming my understanding of the divine. I knew that I needed a so-called higher power that I could rely on in my recovery from food and body shame, because I had tried everything and nothing was working. But I also knew that I couldn’t trust this God that I had inherited from my spiritual community. And so that felt like a really powerful affirmation, that I could in fact discover and describe the God of my own understanding.

Coming from my background, that felt heretical. Like, am I allowed to do this? Because religion had always been top down. And the sacredness of my own interpretation and experience was never propped up and seen as valuable and worth following. But through encountering this sacred Black feminine, through encountering these sacred images of the Black and female divine, I came to see myself as sacred and came to see my body as part of that sacredness, and an ally, and worthy, and beautiful, and lovable in a way that I had been longing for my whole life. Just my whole life. And now sometimes I look in the mirror and it’s so funny because, you know, I’m 42 now. I have some gray hair; I look middle aged. And I just look in the mirror and I’m like, gosh, you’re so beautiful.

AA: Oh, I love it.

CC: And I love that too. Yes, I absolutely love that. And it’s funny because people often say to me, like at the grocery store, “oh my gosh, you’re so beautiful.” I’m like, “I know!” [Laughing]

But also, I have so much sorrow for little Christena, who in my mid-twenties, according to our white patriarchal standards, was far more beautiful than I am now, who didn’t know it. Just didn’t know it. And I was like, heart-stoppingly beautiful. And so I feel so much grief that I carry about that, but I’m glad that I found the truth eventually. And yeah, it’s something that I’ve been able to really hold onto. I mean, it doesn’t hurt to come to France every once in a while and see these amazing, beautiful images of the divine and be reminded that I’m just like them.

AA: Aw, that’s wonderful. So this leads me to another question before we get into the Black Madonnas themselves. So the declarative title of the book, God is a Black Woman, which again I love, one of the reasons is because it forces a reckoning when you hear it. So I love that, I love the boldness of it. But what would you say to, for example, a white woman? You talk about that on one hand, the Black Madonna is the mother of all and she affirms the humanity and the divinity within all human beings. She’s not exclusive the way whitemalegod is in her love and her acceptance. But on the other hand, it’s really important that she is Black, and there is a special relationship between her and Black women. Being a Black woman, that’s really important too. There are some white women who have kind of appropriated the Black Madonna in ways that make me feel uncomfortable.

CC: Kind of? It’s rampant!

AA: Yes, let’s talk about that.

CC: Yeah, so on the one hand, like she can handle herself and I don’t need to be policing how anybody talks about the Black Madonna. So that’s on the one hand. On the other hand, I think we’ve been missing a Black perspective on the Black Madonna, and I think that’s actually really important. And Bell Hooks, the great Black feminist writer and just everything – ancestor, mother, saint—wrote in 2005 that it’s really, really, really a shame that Black people, particularly African-Americans, haven’t reclaimed the Black Madonna. Because she’s such a powerful icon of resistance against anti-Blackness, and particularly misogynoir, which is anti-Blackness directed at Black women. And I think there’s something really powerful about the Black Madonna’s ability to transform us. And I don’t just mean Black people, I think our entire world is laboring under white supremacy and it harms all of us. And when I hear and see white women teaching on the Black Madonna, and frankly making a lot of money off those teachings, and their way of talking about her is so closely resembling the way mammies have existed in our society. She’s this warm, benevolent, big bosomed, loving resource who’s always available to us, and always welcoming to us. And gosh, I feel like I’m watching The Help, you know what I mean? Where it’s this white family that is completely using a Black woman just for what she can do for them. She literally exists just for them and to serve them. And to me that just feels like more whitemalegod. There’s something about the Black Madonna that should be uncomfortable and there’s something about the Black Madonna that should be inconvenient to white people. And that doesn’t take away from any of her amazing maternal, healing, welcoming, affirming characteristics, but she wants to heal us of white supremacy, all of us, right? She’s been healing me of white supremacy, even in the way she’s been healing me in my relationship to my body. She wants to heal all of us of our white supremacy. And so part of that means recognizing that she’s not your mammy. And actually there’s some accountability if you want to have a relationship with her as a white person, there’s some accountability that’s a part of that. How do you claim a devotion to the Black Madonna as a white person? How do you claim that devotion? What does that look like in terms of your integrity as a white person?

And we often see this obsession with the Black Madonna without any actions that are in line with reparations, that are in line with solidarity with Black women, with Black trans women. And so I think what she’s inviting white people into is bringing their justice into alignment with their so-called spirituality. And she’s all of those things. I think American society in particular has been accustomed to breaking Black women down into pieces that feel consumable. Like the mammy, for example. She’s so much more than a mammy, but they don’t even recognize her as a mother to her own kids, or someone who has feelings, or someone who has needs, and I think that pattern needs to stop. And it’s funny because I’ve had so many conversations with white women about this book and they’ve said, “Well, I really, really liked the book, but I really didn’t like the chapters that were really about your Blackness, because they didn’t speak to me as much.” And I was like, yeah, you’re asking me to be a mammy right now. You’re asking me to contort my story as a Black woman into something that nourishes your white body. You’re literally asking me to be a mammy right now. I am all of me, not just the part of me that feels comfortable and easy for you to digest. And I think that’s what the Black Madonna is inviting us all into. And if we open to that, like in every way that I’ve opened to her sharp edge towards justice, I have just been cleansed. Has it felt cute? Not always. But it’s felt life-giving, like surgery. Yay, you just saved my life! And I’ve got a recovery period here, but I’m going to live now which is better than not.

AA: I’m so glad you talked about that. It sounds like for white people, and again, people who are listening who are going to read the book, it sounds like the Black Madonna is inviting especially white people to do work. It is a different relationship. It’s a different invitation. So thank you for that, Christena, that was so important to hear. So, let’s talk about the Black Madonna a little bit more. We haven’t really talked about who these are, there are many, right? Can you tell us a little bit about the history?

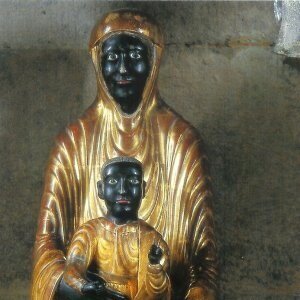

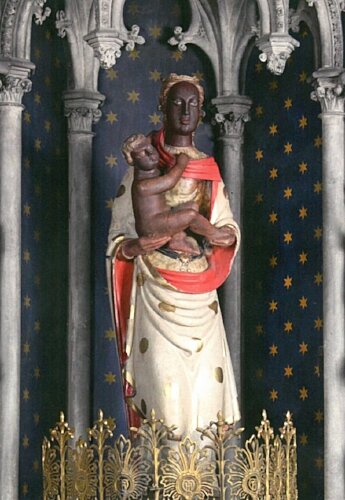

CC: Yeah, I’m still learning myself because I probably wasn’t introduced to the Black Madonna until less than 10 years ago. It’s so hard to know, but there are probably about 450 known Black Madonnas around the world. And these are statues or really important icons that are kind of seen as shrines around the world. The region I’m in France, central France, has a large cluster of them because this is a super old, inhabited part of the world and people have been living in this part of France for thousands and thousands of years. And the pre-Roman people were pagans and worshiped all sorts of wonderful pagan deities like Black Artemis of Ephesus, and Isis, and Cybele, et cetera. All these dark goddesses. And when the Catholic Church came here to France and colonized this whole region and tried to suppress that goddess worship, it was carried on in the form of the Black Madonna here in France. So there’s a reason why there are a lot of Black Madonnas in France. Out of the 450 around the world, a little over 100 are here in France, and about 40 are in this little region that I’m in right now. So this is sort of a hot spot, and they’re often around volcanoes. In 2022 I was in southern Italy with Alessandra Belloni, who’s a wonderful Black Madonna teacher, and her focus is on the Southern Italian Black Madonnas. And they’re all right where Mount Vesuvius is, so the volcanic activity in the same region… the same as true here. I’m surrounded by a chain of like 40 volcanic mountains. And so you often see these super sacred sites being built up in these volcanic regions where the earth is especially active. And so it’s not surprising that there are a lot of Black Madonnas here or in southern Italy as well. And basically they go back much deeper than the Catholic Church, but nowadays they’re mostly associated with the Catholic Church. The Anglican Church has a couple of Black Madonnas and some Eastern Orthodox churches venerate the Black Madonna. But for the most part, they’re found in Catholic churches or Catholic pilgrimage sites. There are a ton of them on the Camino, and so people can visit them as they’re walking the Camino in France and Spain. And a lot of the ones here in this part of France are pretty old. Arlesheim, who was historically one of Jesus’s 72 disciples, supposedly came to this region of France pretty soon after Jesus’s death and brought with him some Black Madonnas. And so there are few in this region that supposedly date back to him. There are also a few that, according to legend, were carved by Luke of the Gospel of Luke. So they’ve been around for a while. Some were brought back from the Crusades, and so a lot of them came around the year 1000 or in the 11th and 12th centuries.

One of the things I love about the Black Madonna, in addition to just the fact that I can stand before this incredible icon of resistance, as bell hooks says, and affirm that I am sacred too, is they’re art! And I think that art is such a powerful stimulator of my spiritual imagination. Whitemalegod infected my spiritual imagination in a large part through art, right? Movies, going to museums, going to churches, and seeing these depictions of a white Jesus. So it’s really powerful to see how different artists over time have sculpted these Black Madonnas from lots of different materials, lots of different time periods, they all have different stances, they have different looks in their eyes. They have different stories. In my book I say they’re kind of like Marvel superheroes. They all have their own origin stories. Some of them supposedly just appeared in the forest, and others were lovingly commissioned by a community like 1500 years ago and then after they were commissioned all of a sudden miracles started being associated with them. But it’s really fun to go, and particularly in this region of France, and I’m in the Auvergne region which is the heart of central France. They call it deep France like the deep South, just like super French, super old-timey. And the Black Madonnas here, I mean there’s one literally in the building next door next to me. I’m staying in an apartment building right next to the big cathedral, the big gothic 12th-century cathedral here. And there’s a Black Madonna there, Our Lady of the Good Death, and she is Romanesque and is just super dark skinned. She looks like she could be a woman on a plantation, in terms of she has very African features and really dark, dark chocolate skin. And then just a three-minute walk down the street, there’s the Black Madonna of the Port and she’s in a cool basilica, and she is like 12 inches tall, almost like a miniature Black Madonna, and she’s in these flowing robes and looks a lot more like a Renaissance woman. And so, from one to the other they look vastly different and tell a really different story about how the divine shows up in the world.

American society in particular has been accustomed to breaking Black women down into pieces that feel consumable. Like the mammy, for example. She’s so much more than a mammy, but they don’t even recognize her

And so I love the invitation. I love the fact that they are art, and because art is open to interpretation. And to me, that really empowers my spiritual imagination because I can walk up to them and ask myself, what is she saying? And that was something that I never felt like I could do with whitemalegod. Whitemalegod always was out there like declaring things, proclaiming things to me. And I feel like there’s something about the Black Madonna, and really about the sacred feminine in general, that’s really interested in collaborating with us in how we experience her. And one of my favorite things about the Black Madonna is that there are tens of thousands of known names of the Black Madonna. And communities call her different things, even one Black Madonna might have four or five official names, because the names are based on how people have experienced her. So she might be the Princess of Peace or the Queen of Peace. Or she might be Slave Mama, or she might be Our Lady of the Sick. And what’s fascinating is there’s this fourth century Eastern Orthodox prayer that people have been praying forever and ever to the Black Madonna, to the sacred Black feminine. And the whole prayer takes like 35 minutes to pray, and within it there are just hundreds of different names, it’s mostly like a litany of names that they’re just honoring her. And one of them is the Enclosure of the God Who Nothing Can Enclose.

AA: Oh, I love it.

CC: The Enclosure of the God Who Nothing Can Enclose. And the next line will be like Our Milk and Honey, so something very intimate and something super transcendent, and it’ll go straight to the intimate and the embodied. And I love that she’s inviting us to name her based on how we experience her.

AA: Well, I’m glad you brought it up because your names for the Black Madonna made me laugh out loud. I love them so much!

CC: Yeah! [Laughing]

AA: And so that’s fun to hear that that’s part of a broader tradition of inviting.

CC: Yeah, I didn’t know that when I started naming her.

AA: Oh, you didn’t?

CC: No, I didn’t, it just felt empowering to me, you know? I was standing before them, and this was on my initial pilgrimage in 2018, I had walked 400 miles to visit all these 18 different Black Madonnas. So by the time I got to them I had walked the whole day, and was super in my body and super present, you know, finally gotten out of my head. And so the names just came out of this experience. So it was really fun to come back home, do more research, and realize that this is something that she invites us into. And maybe that’s what I felt, like an anointing or a permission or a consent, you know? But yeah, she’s so relational, right? She’s so different from Jehovah, the God that I grew up with, who shows up on Mount Sinai and throws down tablets of proclamations and commandments. She’s like, let’s be together and let’s have some accountability and a relationship together. And let’s participate together, let’s collaborate on what this relationship is going to look like. And I love that. Yeah, so I met She Whose Thick Thighs Save Lives, Our Lady of the Side Eye, She Who Loves by Letting Go, She Who Cherishes our Hot Mess, who’s only about a 30-minute train ride for me right now, and I’m hoping to go see her before I leave. But yeah, it’s just so powerful.

AA: Yeah. As we wrap up, I would love to close out the episode by hearing about one of them. I mean, I know you have tons of favorites so I’m not asking you to choose the definitive favorite, but a special experience that you’ve had with one of them. Name which one it was and what was a special experience for you?

CC: Yeah. So last week I went to Lyon to spend the day with a friend, and there’s some wonderful Black Madonnas in Lyon as well that aren’t in my book, but are definitely worth looking up and reading about. But on my way home from Lyon, on a 2.5 hour train ride, I got some really, really painful news about a loved one who’s quite sick and I’m not sure what’s gonna happen. And I was just on the train, I was so grateful to be on the train at night in this sort of meditative space, and I couldn’t see them but in the morning I had seen them so I knew I was moving through these volcanic mountains that had been known to be sacred for thousands of years. And this area was actually called ‘Nemasos’, which means ‘the sacred forest’ by the pre-Roman Gauls who lived here. And so I was just holding this grief, and this is someone who I feel has done a lot of work on their part to release me to the Black Madonna and to release some control that they had over me. And some of that work might not have been conscious but it’s happened, and I’m really grateful for that. And I was sort of thinking about my own care for them, and the distress that I was carrying around, this illness and just the uncertainty about what will happen. And it’s like I felt the Black Madonna speak to me. “You know, they relinquished you to me. Can you relinquish them to me?” And I just started to cry and I realized that this is a grief that I don’t have to hold on to. And this is an uncertainty that I can share with her. And I looked up and the train at that moment was passing through Vichy, the Vichy stop was on the way home to where I am. And Vichy is where Our Lady of the Sick, who I nicknamed She Who Cherishes our Hot Mess, Vichy is where Our Lady of the Sick lives. And I just thought, oh my gosh, what a powerful reminder that she’s Our Lady of the Sick. I can absolutely relinquish this person to her. That’s what she’s for, that’s why she came to this region. And I feel like that’s what I love so much about the Black Madonna in particular, but Marian shrines in general, that there are these particular gifts that they offer us. And they vary based on the shrine. And in that moment I needed to know that Our Lady of the Sick was holding my beloved, and that I could let go in a way. And I just felt so much more free. And of course, the grief and the sorrow is still there, but not in a way that I feel responsible for it or weighed down, if that makes sense. I feel so much more accompanied. And who knows what will happen, but I know that She Who Cherishes our Hot Mess—and this is also a person who’s sick and also a hot mess of a relationship, but it’s complicated, right? Like so many of our relationships are. She’s holding it all and she’s present to it. Yeah, that’s just like literally last week. A day in the life.

AA: Oh, thanks for sharing that. That’s just beautiful. Thank you so much. And thank you for this conversation, thank you for writing this book. I’m so grateful I found the book and so grateful to be connected with you. I just admire your work, I think it’s really critical and I learned so very much. So again, I really recommend to listeners that you purchase the book and read it, and we’ll also have images of the Black Madonnas on our website so that listeners can see, because it’s really powerful. You have the images of the statues in the book and it’s amazing to see them. So we’ll have those on the website as well.

CC: Yeah. Oh, I love that!

AA: Dr. Christena Cleveland, thank you so much for being here today.

CC: Thank you. It’s such a joy to connect, and thank you for having me.

I came to see myself as sacred and came to see my body as part of that sacredness…

an ally, and worthy, and beautiful, and lovable.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!

wonderful post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector do not notice this. You must continue your writing. I’m confident, you’ve a great readers’ base already!