“There’s a dollar number attached to menstruating. ”

On today’s episode I’m joined by Emily Bell McCormick for an interview about the impacts of period poverty and the battle for economic justice unfolding in state legislatures right now.

Since Emily and I recorded this interview, House Bill 162, Period Products in Schools, was unanimously approved by the House Education Committee. Currently, the bill is awaiting a vote from the Utah House of Representatives which will ultimately determine its fate. For those interested in getting involved with the fight against period poverty, or any of Emily’s other incredible work, please visit The Policy Project.

Our Guest

Emily Bell McCormick

Emily Bell McCormick (she/her) is founder of The Policy Project— a U.S. non-profit organization made up of individuals and like-minded organizations that help educate around and move forward healthy, long-term policy at a local and national level. Emily is also the editor of Utah’s NBC affiliate KSL Studio 5 “Smarter” series–informing viewers about issues, government, policies and politics of the time and helping to empower viewers to find their place in it all. Emily is an experienced communication strategy consultant with a history of working in a myriad of industries including government, policy, NGOs, tech and fashion. Emily has a master’s degree in communication from The Ohio State University and a bachelor’s degree in broadcast journalism from Brigham Young University.

The Interview

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy. I’m Amy McPhie Allebest and today I’m here with Emily Bell McCormick—welcome Emily!

Emily Bell McCormick: Thank you. So excited to be here with you.

AA: By way of introduction: Emily Bell McCormick is the founder of The Policy Project, which is a US nonprofit organization that helps educate around and move forward healthy, long-term policy at a local and national level. Emily’s also the editor of Utah’s NBBC affiliate, KSL Studio 5’s ‘Smarter’ series which informs viewers about issues, government policies, and politics of the time, and helps to empower viewers to find their place in it all. I’ll also mention that Emily is involved in the movement to pass the Equal Rights Amendment in Utah. And she was one of our reading partners on Season One when we read and discussed the ERA.

Emily we’re so excited to have you back today. Thanks again for being here.

EM: Yeah, absolutely this is such a great podcast! I love it. Big fan.

AA: Thanks. Okay, so one of the reasons I wanted to have you back on the podcast is because I recently attended a fundraiser where you talked about some efforts that you are heading up in the state of Utah. You described lots of different things that were totally thought-provoking and so important, but one of the mental images that I took away from that fundraiser as you were speaking was this dynamic where you’re talking to male legislators about some women’s issues. The image of you sitting across a desk from a man in power really struck me as a dynamic that I wanted you to talk about on the podcast because you were so, so brilliant and so capable and experienced and well-spoken…but it was still this unequal power dynamic that really struck me as a visual representation of a patriarchal power structure, and so I’d really love to hear about some of the projects that you’re heading and that you have going on, and your thoughts about how patriarchy plays into those issues.

The first thing I wanted to ask you about is The Period Project—if you could tell us about that project, and then if and how you’ve seen patriarchy at play in The Period Project, or the need for it, I guess.

EM: Yeah, absolutely. You know it is a very fascinating kind of vignette or microcosm of this larger picture of how in the year 2021 these things still play out because a lot of times, I know obviously in the work you do and definitely in the work I do—which is policy work related to gender equity and gender equality—I’ll hear a lot that people ‘feel equal’ and I love saying ‘You know, equality is not actually a feeling. I’m glad you feel that way, but it’s actually a metric; it’s something you can quantify.’ And particularly in this work that I’m doing now, you definitely see how these structures that have been in place since before you or I were born, way way before that, continued. Right?

So I have a group called The Policy Project, and our current work is called The Period Project and what this is is work surrounding menstrual policy. Menstrual policy is kind of a new concept and the idea is that we have policies regarding everything you know, like the cost of your gasoline, the cost of your milk. We have policies around men’s hair growth drugs, for example. We have policy around what toilet paper costs. Policy is throughout everything in American life and in most other countries as well. But definitely here in America.

As we looked at policy and what is holding us back…you know, we know that women and girls specifically don’t enjoy full equality in our systems and part of that is because of the way that policies are implemented. Policies that haven’t implemented, those that are just lacking because of a lack of awareness and those kinds of things.

(Sorry we’re getting really fundamental here into how the issue of menstrual policy came up.)

So in looking at like Why?

Why is that?

Why is it that women are still not equal?

You know, in the state in which I live (which is in the western United States), my state was ranked 50 out of 50 for women’s equality…so came in dead last and has been for the past four years, and for at least a decade has been in the lowest five. This is an ongoing problem, and when you look at that and what is affecting this and what’s something concrete we can do—specially when you’re looking at more conservative states, it tends to be a little bit of a bigger battle in those states. One thing that we found is that menstruation, this very natural occurrence for every single female who is born (it affects fifty percent of the population over time) this has never had any policy around it. I’m saying absolutely nothing, right?

I’ll hear a lot that people ‘feel equal’ and I love saying ‘You know, equality is not actually a feeling. I’m glad you feel that way, but it’s actually a metric; it’s something you can quantify.’

We know because we’ve just been through covid that other public health issues affected a third of the population… the end of 2020, there was a study and it said that one in three Americans had been affected by covid and we have so much policy around that. And we’re all very familiar with that policy now; mask mandates and vaccines being implemented as soon as they could, research in vaccines immediately and businesses shutting down and all these different kinds of things that we implemented. But we’ve been dealing with menstruation since the beginning of time. Literally menstruation was critical to begin time for humans, right? We have to menstruate to procreate…and nothing had been done around this. And so what we have done is basically looked at what are some quantifiable things that we can do, policies that we can put in place, that help deal with menstruation.

Three or four years ago when I started this work on menstrual policy, we looked at something called ‘the tampon tax’ and that was basically getting rid of a sales tax on menstrual products. You know Rogaine does not incur sales tax. Viagra? It does not incur sales tax. Band-aids, sunscreen, much lesser items don’t incur sales tax…but period products were incurring sales tax.

So we got to work on that here in Utah. It had actually been introduced for four years prior, this idea that we call the tampon tax, of ridding our state of the tampon tax. There was a woman who introduced it in in my home state of Utah and a legislator who had introduced it, and in those four years prior there was a bill filed. The way the legislative process works in the US, things get broken down into committees, right? And these committees (made of six to ten people, depending on what it is) sit and they evaluate bills to see which ones are worthy of actually having a vote by the full legislature. So what happened in these committee meetings here in Utah, prior to me being a part of this conversation, was that this bill to get rid of the tampon tax was filed by a female legislator who was a Democrat. It would go to these committee meetings and in these four committee meetings (you can go back and listen to this) the word “menstruation” was never brought up. The word “period” was never brought up. And it was all male committees, and every single year it was killed, so it would die before it got a full vote.

It was determined in those committee meetings that this was not essential enough. That it wouldn’t be voted on. Meanwhile we have policy regarding men’s hair growth and regarding erectile dysfunction—these are just facts, right? Those things have been having policy around them and this has not.

AA: One question I have is: what is their reasoning behind not taxing Rogaine or sunblock or whatever? Is it because those are deemed essential needs or something like that? What’s their reasoning?

EM: Great question. Those are deemed ‘medically necessary’. That’s terminology used by the IRS and what our state adopts, by nature of the IRS having that definition, our state adopts the same to do a sales tax. So the IRS never recognized period products as a necessity, as “medically necessary” and therefore our state also did not deem those things as medically necessary; it’s really interesting because they’ve just been left out. And frankly, Amy, when you look at it you realize this is not necessarily the function of a male legislator or legislature or a male congress saying “We hate women,” right? I know that you and I are familiar with this. It’s oversight because we don’t have women present. We don’t have women’s voices in those spaces even to this day. We don’t have enough where it’s being talked about or it’s like oh this isn’t our place, right? So a more innocent version of this is like “Ah that’s a woman’s issue. We shouldn’t be involved in that conversation…But we’re involved in all other parts of their lives.” You and I are also very aware that there is plenty mandated around women’s bodies and it’s so interesting that we want to withdraw from this conversation, but we’re involved in others.

AM: Wow, the irony of that. Okay, and then what you’re saying also is men can plead ignorance to a point right? Like if no one’s ever brought it up, we can give them at least the benefit of the doubt for that. But you’re saying that there was a period that this was being introduced in the meetings and somebody was looking at it and deciding this isn’t a high enough priority. So then they couldn’t plead ignorance anymore, right? They’re seeing that there’s an issue.

EM: Absolutely, that’s exactly right. At that point it is on their shoulders?

I started getting involved in this work a couple years after it had been introduced in my home state and had been introduced in some other states within the US, and that’s when I got in and said “You know what we need is a good messaging campaign. We need to reframe this. We need to make men feel their responsibility in this.” Because ultimately what we really needed to do is convince our conservative male leaders and conservative female leaders in our state that this indeed was something that should be legislated around. But we really needed to reframe the issue entirely, and so that’s when I got involved and that’s the fundraiser that you’re talking about, that’s where I spoke.

The way that happened was basically getting some other really great men involved. You know, I had a couple lobbyist friends who were male who, after explaining the issue to them, were like yeah we can totally see this. Let me make some introductions and I landed in a lot of male legislators’ offices, sitting on their couches, at first doing the gentle introduction like “Hey have you ever considered supporting this kind of legislation?” We really needed to equalize the way that we look at public health and medically necessary things. And then, when there would be a lack of understanding or a lack of buy-in, that’s when I got really personal and made it really awkward.

I can remember one meeting in particular, sitting in a male legislator’s office with the male lobbyist who introduced us (and this male legislator is truly a good man) and having to say where it wasn’t resonating: “Let me tell you something. If I started my period right now and I was sitting on your couch, I would bleed on your couch and it would make it very awkward for you.” I know there is a certain amount of humility and embarrassment that comes along with that conversation even though I talk about this every day in that setting. It wasn’t like oh this is so easy and I don’t give a crap. It’s uncomfortable to get that personal and to say “I want you to think for a second about me starting my period. And now that you’ve thought about that, I want you to think if I were your daughter sitting here and starting her period when she’s trying to talk about something that really shouldn’t have to be talked about.”

Many groups of people can’t believe this is even an issue and to have to explain it and get so personal so that they can finally feel it—it’s tricky right? We shouldn’t have to go that deep, but we are required to at this point in time for sure.

You and I are also very aware that there is plenty mandated around women’s bodies and it’s so interesting that we want to withdraw from this conversation, but we’re involved in others.

AA: So your talent is getting that personal, which takes so much courage. I mean you’re saying it’s kind of embarrassing and it takes humility, and it does but the courage to do that… I’m just in awe. That’s amazing and it’s infuriating that you have to take it to that level. But what you’re trying to demonstrate to him is that this is a necessity, this is a medical necessity to have period products, to have tampons, and so it’s unjust to say that they should be taxed, right? And that’s a burden. It does add up for people of limited means to have extra taxes on things that are medically necessary. That’s a class issue as well as a gender issue in my view, is that right?

EM: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. We know that these kinds of issues impact people who are low-income, people who have experienced a lot of trauma in their lives; it often is with communities of color. You’ve got so many things in the policy world where the people who are hit harder get hit even harder, and that would absolutely be true of that.

I’ll take you through the timeline to today. So we worked on this tampon tax, right? And we finally figured out a way; I got a couple male legislators who really bought in and were willing. They didn’t want to say the words, but they were willing to let me be the mouthpiece of this and they were willing to support. There was a great man, Robert Spendlove, who really got behind it and was willing to take this on and open a bill file. I knew that I needed a male and I needed it to be a Republican and I needed him to be conservative, and he was able to get on board. Because of that we were able to slip this tampon tax into a larger tax reform bill that was happening at the time that dealt with the entire tax code in the state of Utah. There was some hesitation by legislators, and not just males, some females that were against it, but we were able to pass this and as a part of this larger tax overhaul now.

Fast forward—there was a big public campaign. People didn’t like one element of this: there was a food tax attached to this big tax reform bill and so there was a lot of public outcry and the tax reform actually was overturned one month later. So for one month, period products were tax-free in the state of Utah.

So that happened to line up with a legislative session and we were able to reintroduce it as a separate bill and it ended up not passing, and the argument was (we got it through essentially the House of Representatives, but when it got to the Senate) they said we don’t really like these carve-outs in our tax code.

Let me just mention quickly some carve-outs that Utah has in its tax code: snowmaking machines. We have ski reserves in Utah (it’s a big ski place). They’re not taxed. Car wash tokens: not taxed. Arcade tokens: not taxed if you have attended any type of university or college sporting event. None of those tickets are taxed, so the amount of tax revenue that you could get out of a sporting event at a collegiate level is close to $14-16 million a year. The tampon tax? Less than a million. We had it earmarked for a million dollars. So if you’re talking about income from sales tax revenue, there’s not even an argument there for this. But it died on that cross, right? That’s why they would not pass it this year, because they didn’t like carve-outs. But we know there are a million other carve-outs in our tax code because the lobbyists were strong in those areas.

You and I can look at this and say that there is a gender equity issue here for sure, that there’s a lot of bias going into this decision making. Especially, frankly, when you see women legislators get on board with voting against it. It was kind of fascinating, like, oh we’re all buying into this gender discrimination, right? And to gender bias?

After that I really had to take a step back and look at what is possible. What are we able to ask our legislature to do, because 75% of our legislature is male here. It used to be 80%; we’re now down because we just got one more female (that’s exciting for us!). So we pivoted and actually I left the tax behind. The tax is symbolic. It’s the right thing to do and it’s equalizing and it’s not going to get done here in the next couple years because the legislature is not going to do it.

What we looked at next was what the impact would be for women and girls and people who menstruate in our state to put period products in schools. And the impact of that is so much greater, so that’s the legislation that we’re currently working on. We actually have a bill file open to put period products (that means tampons and pads) into every public and charter school in the state of Utah.

AA: Okay, awesome. Tell us about that.

EM: It’s not middle school through high school, it is K-12 because we know that 10-15% percent of students who menstruate start at age 7. And in communities of color where there’s more trauma and low income, that number is closer to 38% of those kids are starting at age 7. I have a 7-year-old. She’s in first grade. She’s not developed at all. I can’t even imagine what that would be like.

And so these kids who have already experienced difficulty in their lives are also experiencing this, and that makes for a very difficult situation. We know that having these supplies in bathrooms will make a world of difference for these kids.

One thing that’s interesting that we found as we’ve worked with male legislators and especially through the tampon tax, is that you learn. You go through these things, you get a little bruised, a little banged up, but you also learn. And one of the things that was so fascinating is that when we have a lack of representation you think it doesn’t really matter, but there is a fundamental misunderstanding about menstruation. You know all genders experience bathroom issues. Everyone has to pee. Everyone has to poo. Sorry to get graphic on you, but it’s real and you and I both know that if in the middle of this podcast I needed to go number 1 or number 2, I would just say “Oh damn, I have twenty more minutes. I’m just gonna hold it, right?” So that was a perception that it took me getting through the tampon tax to realize that men did not fully understand. Even if they’re talking to their spouse. Even if they’re talking to their children. Even if they’re talking to a sister, a mother—someone about menstruation—they didn’t fully understand that menstruation can’t be held like other bathroom issues. Which actually, when you think about the logic: if you’ve never experienced it, you don’t know that necessarily. And so reframing the messaging around menstruation.

This is why representation matters, right? Because female legislators, if they voted against it that’s on them because they know that it can’t be held. But we started using the messaging: like a bloody nose, menstruation is involuntary. We cannot control it. It’s spontaneous and it’s involuntary, so when it starts it has to be cared for immediately. If it’s not cared for immediately, it interrupts everything else that you’re doing, right? You’re unable to finish your classwork. You’re unable to continue your presentation at work. You’re unable to continue grocery shopping. Everything. Any activity you’re doing is immediately interrupted because of menstruation.

…they didn’t fully understand that menstruation can’t be held like other bathroom issues. Which actually, when you think about the logic: if you’ve never experienced it, you don’t know that necessarily.

Patriarchy and gender differences are so fascinating because some of those basic arguments have to be made, and I didn’t even realize I had to make that in the beginning.

AA: Totally. What I keep coming back to is even the title of Simone de Bouvoir’s The Second Sex. It’s like the default is a male, that’s the default human, and then a female is secondary and an afterthought and like…What is the female reality? And for men in 2021 to not even know, it’s kind of astounding actually, Emily. I can’t believe it. But it really does highlight that dynamic of ‘the default human is the male’ that our whole society is structured around this, and they could be that ignorant of the way human bodies function. I’m kind of floored to be honest.

EM: Yeah, it is actually kind of flooring. I mean the reason you’re feeling that is because, again, I think that this work in menstrual policy is such a microcosm of everything you talk about on your podcast. You know, it’s a modern-day play of everything that we’re talking about and what it looks like in 2021. And you talk about that the default is male, and I just had finished reading Invisible Women, that book about statistics. There’s no emotion behind it. It’s just like, statistically the world has been set up for males and that isn’t something to argue with. It’s just numbers. And so I love that and that is absolutely true of legislation and policy.

Everything has been set up around males because they’re the ones making the laws and the responsibility in this moment. It’s an interesting argument too, because the responsibility is on both parties. Because males are the ones in power generally, and to this day they still hold the majority of power in most states and in our country, there’s a heavier responsibility on them.

But the reality is, as women, we need to get over our own biases that we experience about our own gender and start talking about these things more openly. Because you and I can go tell our sons or husbands or friends that are men about menstruation, and the important thing is that we start doing that, we have to start being more open about it.

AA: Absolutely. At the time of this recording, we haven’t yet released the episode on the book Unwell Women for Season One, but that’s another must-read and I actually do share a period story on that episode and I’m so uncomfortable. So when listeners hear this episode, they will have already listened to that on Season One. At the time we’re recording it we haven’t yet, but that was one of my huge takeaways, goals, and commitments: I am going to talk more openly about my own experience as a menstruating person, as a female. Because yeah, like you said, to a point men can’t be held responsible if they’ve never had the experience and no one’s ever told them before. So that’s a really excellent point, that part of the responsibility is ours to get over our embarrassment and our internalized misogyny that we’ve inherited and just be like No, we’re talking about this. I refuse to be embarrassed about this anymore. It’s a great point; something we can do.

EM: Yeah, and it’s interesting because when you think of groups that have been marginalized throughout time, and this isn’t always true, but we’ve seen some different sections take back words or ideas that once harmed them and own it as a group.

I know that some of that ideology is debated, but the reality is I think that we need to do that as women. Because the interesting thing about menstruation is that when we talk about or think about words and the context in which we use….It’s actually acceptable to be like oh she’s on her period or oh she’s just PMSing. Men can actually say that, which is so interesting. And yet we would never hold them accountable for providing period products in the workplace.

You get into the logistics of managing a period or, heaven forbid, and this is way far down the line, but when you think about it: women do experience PMS. What about having a couple hours of leave for when they’re having PMS? You know there are a lot of policy considerations that are so far out there. I won’t even go there quite yet with our legislature, with the federal government, but there are a lot of things to be considered in this. It’s a very real thing that affects women and people who menstruate.

AA: That’s such a great point that a man can make fun of it, but hasn’t felt any responsibility to actually help take care of the real issues of it. Yeah, that’s such a good point.

Okay, so can we talk a little bit about period poverty? Because we talked about with the tampon tax that adding a tax to menstrual products is a hardship, but you said you know that providing period products in schools is a way bigger issue that can help people so much more. Could you talk about period poverty? What that means, how many people it impacts? What does that feel like for a girl or family?

EM: Absolutely, this is a really interesting thing and really what drives me to do my work. We’ve recognized certain things, like food, as such a necessary item. In schools, we’ve figured out it’s worth giving kids like a free breakfast and a free lunch because if we don’t give them that they can’t concentrate, right? Like presenteeism, being present in what you’re doing. They’re unable to concentrate. And so this idea of providing these basic needs…it’s not new to us. It’s not new to conservatives and it’s not new to liberals, right? It’s not new to any of us. We’re all familiar with that.

I’ll get back to that in a second, but period poverty is this idea that experiencing a period actually increases your poverty. And it does because we know that for women, girls, and people who menstruate, they experience it on an average of three to five days a month for an average of 40 years in a lifetime, and those 40 years are right in childbearing years. They’re right in your main workforce years. They’re right in the middle of all of that. And there’s an expense. There’s a dollar number attached to menstruating.

We know that depending on where you’re able to buy your period products…you and I may be able to go to Costco and purchase 100 tampons for $12, but the reality is that someone who’s already in poverty—they’re buying seven tampons at 7-Eleven for $7 dollars. So experiencing a period has an actual number attached to it. And those numbers have been estimated differently, but over the course of a lifetime it’s thousands and thousands of dollars.

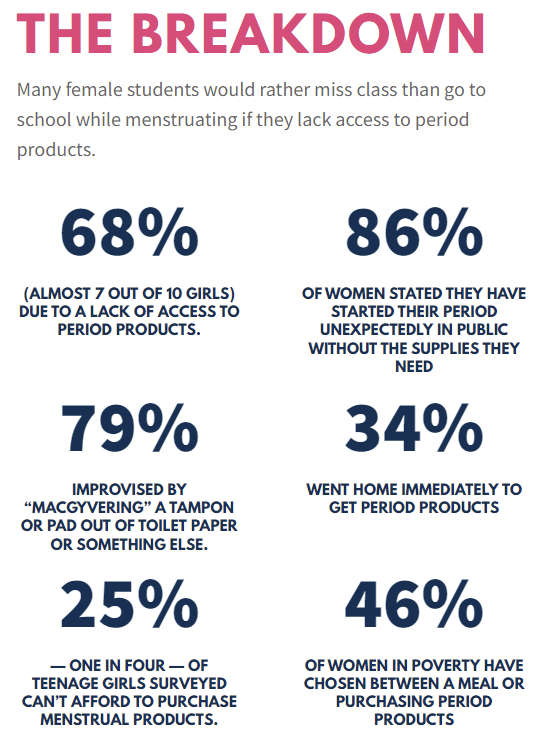

That’s not compensated for or made up for in any type of healthcare. We don’t even recognize it when you go into your doctor and you get your health form about have you fallen or not since your last visit? You’re not even being asked about menstruation. We’re trying to change that, but these things are not recognized in the most basic of spaces and so period poverty really is an illusion. It’s a catchphrase for the added poverty that women experience because they experience menstruation. So if you’re in poverty, you’re experiencing period poverty without a question. We know that half of women, 46% of women who experience poverty have to choose every month between a meal and a period product. If you have children that number goes up. And this is just as a single woman (that’s what that data is, it’s for a single woman) so if you experience period poverty and/or poverty and you’re looking at: listen I can either feed myself and my kids or I can purchase the tampon…you’re not buying a tampon. I can almost guarantee you that. We know that 1 in 4 teens cannot afford tampons at all. We also know that 1 in 4 students have missed class because they can’t afford period products. So these are very real numbers that affect you in serious ways.

Sometimes it’s hard to have those statistics resonate, so let me tell you a little bit about what that looks like in a day-to-day life. In my very own neighborhood, I live in a school district where we have a homeless population and we have some of the wealthiest people in our state. It’s a very socioeconomically diverse school district. And in talking to one woman who grew up in this district… she grew up with parents who were unable to care for her because they had addiction issues and so when she started her period she would stay home.

…you’re looking at: listen I can either feed myself and my kids or I can purchase the tampon…you’re not buying a tampon.

Every month she would lay out rags on a couch and watch TV while she was menstruating. So we know that chronic absenteeism in our school districts that starts affecting graduation rates is two days a month; if you’re bleeding for three at the minimum, up to seven-eight days at the max. You know, I have family members who bleed for seven days a month—she’s missing all that school, right? I think she did graduate, but she’s continued to struggle with poverty. She’s a 40-year-old woman.

There’s a girl in a neighboring school district who is a recent immigrant and she talks about the fact that her family buys cotton balls because they’re less expensive than period products. And she and her sisters do not go to school because the cotton balls fall out of their pants and that’s really embarrassing. So they’re not even going to school.

We recently spoke to a custodian at a local school that is well-funded. Our standard of living in America is no joke, we have a great standard of living. Most of these kids even have access to cell phones, but because it’s so unacceptable to experience poverty and to have it be visual (also because it’s happening to females) menstruation is not talked about. One of the custodians at a local school district said that every single day she wipes blood off of classroom seats—not bathroom seats, classroom seats—when kids go out to recess. So she’s wiping blood off of these seats…she was so struck by it because she knows these kids go home after that. They’re not coming back to class when they bleed on the seats. They don’t come back and so it affects their education.

A lot of times what happens in policy is these issues that are considered women’s issues or children’s issues—we get sidelined. We do not get funding. We do not get the attention other issues do and so one of my goals has been to really reintroduce us as an issue of workforce. Because if you’re working at 7-Eleven and you’re bleeding, you’re not going to work. The next day if you can’t care for your period, you’re not going to work. If you’re a child in poverty and you’re bleeding at age 9 and you don’t have parents who care for you, you’re not going to school. I wouldn’t go to school. And a male legislator would not go to school because they’re doing that, right? We know that. So we have to reposition these issues as workforce issues.

But it’s really important to look at these issues and broaden the conversation, because as much as you and I are ready for men to take on every women’s issue in the world and get it done, we have to show them that it counts for our economy. It counts for our workforce, it counts for education, and it ultimately benefits men because—as sad as it is—we’re all self-interested, right? Until it does, we will not make a splash with these issues.

I can tell you that in my state where we consider ourselves to have kind of low numbers of workforce. We know women make up 40% of our workforce in our state. 60% of women work. And this is in a state where culturally (and with the majority religion here), women don’t work as often, and even here we’re a massive part of the workforce. So it’s not okay to ignore these, and what’s being overlooked is that when we ignore women’s issues we’re actually doing damage to the entire system. That when these things are cared for we all are lifted, including men, including men in power. We all do better and it’s a very misunderstood thing.

…women’s issues or children’s issues—we get sidelined. We do not get funding. We do not get the attention…

AA: And yeah, wow that was just stunning and you talked a little bit about this at the fundraiser that I attended but just hearing it again… I was aware of period poverty as an international issue in developing countries and I have volunteered before making period products. Reusable ones for Days For Girls that were being sent to other countries. But hearing you talk about it again at the fundraiser and today, just to be reminded that this is happening in our own neighborhoods to people we know, and we would never even know it because there’s so much stigma and shame around it. So it’s sobering. And it makes it that much more urgent that this is a problem that we can solve in our own community. So how can we get involved, Emily, how can we help this problem get solved?

EM: That’s such a good question and thank you for asking it, because we can all do something and there are a few different levels of involvement with us. It’s donating product, donating tampons and pads to local homeless shelters, local schools, food banks, whatever your community has depending on the state that you live in. And that’s an important piece of this, right? But ultimately that does not solve period poverty. And the cool thing about period poverty is that it is solvable in our lifetimes! Poverty is this big, overwhelming issue—women experience it at much higher rates. I’m sure you know this, and I’ve talked about this before—but the reality is that we can remove this barrier in our lifetime, which is what gets me super excited inside.

The product donations are really good and we need them because there are people who need products today, but the reality is…You know, Amy, you and I would never remove toilet paper from every single bathroom in schools and restaurants and places of work, in our homes and say “Hey, we’re just going to do a product drive. We’re going to just—we don’t think the government should be involved with this. We’re going to just do a product drive.” The idea of that is so silly! It’s super laughable. And so, when people kind of push back like “Oh you’re trying to make us become a communist country” or something, when I get that kind of pushback…and like, then what about if we remove toilet paper everywhere? Just rely on your kind heart to donate enough toilet paper for us to all use. It’s like that, but even more so because menstruation can’t be held, so it’s almost more critical.

When you think about it in those terms, and you think about the way that it really handicaps women, girls, and people who menstruate, you realize that this really needs to be a policy. We have to have policy involved in this and we have to have governments, businesses, every level of our society get involved in fixing this. The way that you can get involved, that listeners can get involved, is really by, first and foremost, starting talking about it. We need to remove the stigma like, yesterday. We need to remove the stigma two generations ago and 1776. We also need to get women elected to office so that we can take care of these issues. But really, just be a little more open about it. Challenge yourself to mention it to a spouse, a child, a friend—anyone. Challenge yourself to talk about menstruation.

That’s the first thing; the next thing is, of course, donate product. That’s probably the next easiest thing to do. The next level would be reaching out to your legislators, seeing if there are any community organizations in your area that are working on legislation around this; there are several that have cropped up. If not, join us, The Period Project. The Policy Project is the website and come and look at what we’re doing. We’re doing some training for other people in other states, if this is something that really speaks to you and you want to get involved with the legislature in your state or at a national level. Because ultimately we have to have our government recognize this. And then getting businesses involved. If you work, please talk to your business about how important it is to put period products in bathrooms. That’s kind of an embarrassing ask. It’s ridiculous that it’s embarrassing, but do it. Stay where you are.

Lift where you stand is our whole ideology behind this. If you’re a stay-at-home mom, that’s great. You have enormous impact—talk to your daughters, talk to your sons. If you are a woman or person who works, talk about it there. If you have some extra time and could get involved legislatively, do it there. There are a lot of different layers to this one, and just lift where you stand.

Challenge yourself to mention it to a spouse, a child, a friend—anyone. Challenge yourself to talk about menstruation.

AA: I love it, Emily. Wow, I am blown away and so grateful to have you talk about this today. I mean, I’ve heard it before and even today my jaw was just on the floor some of the time when you were talking. This is such an important issue and I’m so grateful that you brought it to our attention. So thankful for the work that you do.

EM: It’s so neat to come and talk about it and I just have to say it’s really exciting if, in your lifetime, you can discover something that’s actually workable, that will make a concrete difference in the lives of women and girls.

In the weirdest way I feel so blessed and lucky to be able to see this, because a lot of things, like…we can see the problem, but we can’t see the solution. To be able to work on a project where there’s an actual solution is the experience of a lifetime, and to get buy-in and to be able to message it in a way that’s resonating. You know we’re going to get this legislation through without a doubt in my mind, and we won’t stop until period poverty is over.

It won’t just be this. It will continue because that’s what we’re doing. The thing that I can see is the thing that I can do. And we are lucky to be in a position where it hasn’t been interpreted over time in a weird way, to have that tabula rasa and start fresh on an issue is just…it’s a chance of a lifetime. So I feel really lucky to be able to be involved in something that will have such a concrete effect for all of us. Not just for our women, our girls—it’s for all people, right? This is men, this is all people, this affects everyone, this makes life better for everyone. It’s a really new opportunity to be doing this.

AA: Super inspiring. Well thanks again, Emily Bell McCormick, for being here today on Breaking Down Patriarchy.

Lift where

you stand

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!

Today a reader,tomorrow a leader!