“Thank you so much, anger”

In the concluding episode of Season Two, Amy is joined by Dr. Kristin Neff to discuss the generative power of anger, the danger of rote gender roles, and the radical power of self-compassion.

Our Guest

Dr. Kristin Neff

Kristin Neff (she/her) received her doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley, and is currently an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin.

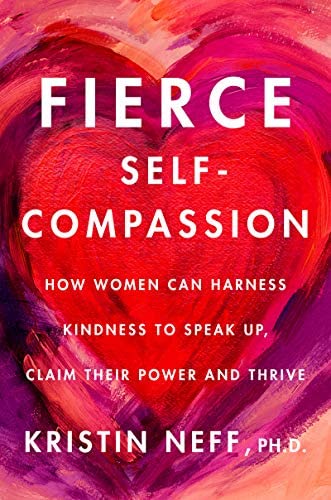

During Kristin’s last year of graduate school she became interested in Buddhism and has been practicing meditation in the Insight Meditation tradition ever since. While doing her post-doctoral work she decided to conduct research on self-compassion – a central construct in Buddhist psychology and one that had not yet been examined empirically. Kristin is a pioneer in the field of self-compassion research, creating a scale to measure the construct almost 20 years ago. She has been recognized as one of the world’s most influential research psychologists. In addition to writing numerous academic articles and book chapters on the topic, she is author of the book Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself, and her latest Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim Their Power and Thrive.

In conjunction with her colleague Dr. Chris Germer, she has developed an empirically supported training program called Mindful Self-Compassion, which is taught by thousands of teachers worldwide. They co-authored The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook as well as Teaching the Mindful Self-Compassion Program: A Guide for Professionals. She is also co-founder of the nonprofit Center for Mindful Self-Compassion.

The Interview

Amy Allebest: One of the questions I get most often from listeners is how do you handle all the anger that comes up as you read all of these books and confront all of these issues from patriarchy. A recent episode that we released in Season 2 dealt with rage, and it got a ton of comments of appreciation and feedback. I think that learning the history of patriarchy brings up a lot of fury for people, but then we don’t know what to do with that anger.

And, on a personal note, this past week was actually really heavy for me. Someone I care about a lot has experienced abuse throughout her whole life–first as sexual abuse when she was a child and then, later, verbal and emotional abuse for her entire marriage–and this woman has just been so beaten down and I became enraged that no one has ever been held accountable for what they did to this individual person who’s dear to me and I ended up venting about my anger to my sister and then I noticed that immediately after expressing all of that anger, I felt guilty. I felt guilty for being angry and I didn’t know what to do with that anger.

So a couple of days later, in preparation for this episode, I was reading the book Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim their Power, and Thrive by Dr Kristen Neff and I felt like entire chapters of this book were written just for me, explaining how to let ourselves process anger in healthy and productive ways for ourselves and for those around us. So today I am so honored and excited to welcome to the podcast the author of Fierce Self-Compassion (and she also wrote Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself) so welcome to the show. Dr Kristen Neff.

Kristin Neff: Thank you so much for having me. I’m really happy to be talking about this issue.

AA: I can’t wait to dive into this and first we’ll just start with a little introduction: Kristen Neff is currently an Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. She’s a pioneer in the field of self-compassion research, conducting the first empirical studies on self-compassion nearly twenty years ago. She’s been recognized as one of the most influential researchers in psychology worldwide.

She is the author of the bestselling book which I just mentioned, Self-Compassion, and along with her colleague Chris Germer she developed the Mindful Self-Compassion Program which is taught internationally and she co-wrote the Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook. Her newest book, as I said I read it this past week–it’s amazing! It’s called Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim their Power, and Thrive and for more info go to self-compassion.org.

I’m so excited and I wonder if we can start off by just having you talk a little bit more about yourself? Who you are and what led you to your work?

KN: So I jokingly call myself a self-compassion evangelist because it’s really all I do 24/7. I write about it. I give talks about it. I teach workshops. I do research on self-compassion. I teach about it. I’m at the University of Texas at Austin right now. Well I’m actually kind of modified; I’m not teaching courses, but I’m still doing research. So I’m the Self-Compassion Lady to put it bluntly, and the reason I’ve devoted my life to it is just because of the tremendous difference it makes in our ability to cope with difficult emotions including things like anger, but also any sort of pain, sadness, upset. So ‘passion’, in Latin, means ‘to suffer’, ‘com’ means ‘with’, so really it refers to how are we with our suffering. Are we kind? Are we supportive? Do we treat ourselves with the same understanding and support we showed a good friend we cared about? Or do we beat ourselves up, you know? Do we shame ourselves? Do we feel like we’re horrible people if we made a mistake?

So really self-compassion means being kind and supportive, and not just being judgmental and beating ourselves up all the time. I first learned about it, gosh, over twenty-five years ago now and I was just so impressed by the ability it gave me to deal with…I was going through a divorce and it really helped me deal with a lot of difficult feelings I was having. Then I got the job at University of Texas at Austin and I thought I’d research it, and so I’ve done a lot of research on self-compassion. There’s over 4000 studies now in self-compassion. It’s amazing.

More recently I started realizing that there’s two faces of self- compassion: what I like to call the Tender and the Fierce. Most people, when they think of self-compassion, they think of its soft side. And self-compassion can be soft, it can be soothing, reassuring, nurturing, accepting, kind of like a mother to her child, you know, hopefully anyway (if we’re compassionate we love our children unconditionally, we support them, we accept them as they are). But there’s also this fierce side that I like to call ‘Fierce Mama Bear Self-Compassion’. In other words, it’s not just about acceptance. We can accept ourselves, but we don’t accept all our behaviors if they’re causing harm. We certainly don’t want to accept all the behaviors of other people if they’re causing harm, and we don’t want to accept all the situations we find ourselves in if they’re unfair or causing harm. So we need to, while accepting ourselves, we also need to take action, to try to prevent harm, to stand up to injustice, to say ‘No’, to meet our needs, to motivate change.

And so I started differentiating them just because people weren’t really that aware of both sides of self-compassion, so that’s my latest book. And I aim particularly at women because gender role socialization really basically messes everyone up. Men are allowed to be fierce, but not tender and women are allowed to be tender, but not fierce. It’s like Yin and Yang: we need both of them to be whole, but gender role socialization really makes it hard for us to be whole. So I wrote the book mainly for a woman just because men need a different book. They need, like, Tender Self-compassion: How Men Could Harness Tenderness to Open Up to Their Emotions, Be Sensitive, Be Vulnerable, and Thrive and it would be slightly different, you know, because the blocks are different.

AA: Yeah, that’s fantastic. What a great introduction and those were the first two questions I was going to ask you, because I was really struck by your Yin and Yang concept at the beginning of the book. Would you like to talk a little bit more about that?

KN: Yeah, so you know Chinese philosophy has really got it right. There’s the Yin and Yang energy of all things, of all of life. So Yin is more soft and nurturing–traditionally considered more female but I don’t like to use the word ‘female’ because men have this energy too. And Yang is more the forceful, active, action-oriented powerful energy of life. Yin and Yang need to be in balance, right? If we’re too accepting without enough fierceness, we may be complacent. But if we’re too fierce or aggressive without enough tenderness, well then we might lead to harming other people or harming ourselves.

So they do really need to be in balance, but like I said, gender role socialization makes it very hard for them to be in balance. I mean, if you look at gender role stereotypes…they’ve barely budged the last thirty years! Men are still instinctively…we don’t believe this cognitively, but we instinctively feel they’re more competent. They’re more active. They’re more agentic. Women are more passive, soft, nurturing. It’s still very strong and it still shapes the way we see the world. That’s why we have to make these things conscious–so that we aren’t so limited by them.

AA: Yeah. I have three daughters and a son, and my daughters–one especially always talks about how she doesn’t like any trait to be labeled as masculine or feminine. She’s like “why can’t we just call them yellow or green or whatever?”

KN: Yeah.

AA: We talk about it just being a toolbox, that all human beings should have access to all the tools that help in different situations. This situation calls for this trait. We don’t need to label it a man’s trait or a woman’s trait, but it…it just calls for different people.

KN: Exactly. Every unique individual will express these qualities in their own unique way, and that’s how it should be. We shouldn’t be put into a box. Whether you’re transgender or cisgender…you know, you might have a transgender woman who’s actually quite Yang or fierce, right? It’s really just each individual person expresses these things in their own unique way and that’s what it should be for authenticity. Or at least that’s what I think.

AA: Yeah, I happen to agree with you. Absolutely.

Okay, so let’s dive more into the gender because at the beginning I thought oh this is a book I need for sure, but I did not expect that it would be so much about patriarchy and that it would be so aligned with a lot of the work that I do and in conversation with a lot of the books that we’ve read on the podcast. So maybe we can just start with a general question: what led you to your research, specifically about patriarchy?

KN: I’ve always been interested in patriarchy and gender inequality. My dissertation research was about rights and responsibilities in the context of Indian family life; i.e. patriarchy, right? I was really interested in the fact that, even though it’s a very patriarchal culture, women didn’t agree with it. So people say Indian morality is duty-base. Well, there’s duties for women, there’s rights for men. But the really interesting thing is the woman, they say “Okay, we go along with it. We feel we have no choice, but we don’t think it’s fair.” They’ve always really been interested in power inequality and patriarchy and how that shapes people’s judgments and actions.

Then, with the self-compassion work, what I started realizing–and kind of when you opened it you started talking about anger and it’s all tied together–this gendering of fierceness and tenderness is intentional by patriarchy. I mean it’s not like one person sat there and wrote it all out, but it serves the function of patriarchy which is that people who are raised to be men are the ones who go out and make the money. They’re the ones who have the power. They’re the ones who are competent. They’re the one who makes decisions. The women are kind of supposed to be soft and accepting and nurturing and likable, which means basically they go along with their oppression. So. The whole thing is it empowers men, it disempowers women.

And even with things like tenderness, right? You would think that women would have more self-compassion than men. It’s the opposite. Because women are supposed to be self-sacrificing. They’re supposed to be tender toward their husbands or their children, but not themselves because they’re always putting other people first. Well who does that benefit if women are always putting other people first? Not women, right? And so I’ve always been interested in this and you know I’ve done research on gender and self-compassion.

And then, if you really want to know what happened, the MeToo movement hit and I had my own experience with the MeToo movement. Someone close to me turned out to be this horrible predator. I was just struck by a lot of the women, what a hard time they had getting angry or speaking up about it. And you know, people just wanted to let it pass because it was easier to, but it’s also because they were raised to.

People don’t like it when women speak up. I spoke up and people didn’t like me for it–but I didn’t care if people liked me for it because I had self-compassion. So again, just realizing how gender role socialization–which tells women not to speak up, not to get angry, just to kind of go with the flow focused on other people–how really that disempowers women and contributes to injustice. And it also harms men, by the way. Men are really harmed by the fact that they have to ascribe to these gender roles which make them emotionally cut off and shut down. It doesn’t help anyone.

…while accepting ourselves, we also need to take action, to try to prevent harm, to stand up to injustice, to say ‘No’, to meet our needs, to motivate change.

AA: Yeah, no, certainly not. And I’ve noticed too, sometimes women (and you talk about this in your book) if we’re not able to process our frustration with our subjugation it often bottles up and then if we’re not processing those feelings then it explodes at kind of inappropriate moments that we haven’t planned. You provide some anecdotes of people who have told you stories about this, like I didn’t recognize myself, I was like a monster, I don’t know what happened. But it explodes sometimes at the wrong guy, like, he’s not the one who invented patriarchy or he’s not even the one who’s contributed, but it just kind of sometimes comes out at men. And so in that way too I feel like sometimes men are like “Why is everyone so mad at me?” and it just is a mess for all involved.

KN: So in order to write this book–because I was framing it in the background of patriarchy because of the fact that women’s fierce side tends to be suppressed–I did a lot of reading on sexism and theories of sexism, theories of patriarchy, and there’s consensus that there are basically three different forms of sexism. The most obvious is hostile sexism. These are people who are misogynists, who put women down, who think women are the lesser sex or, you know, some of the people who are just really anti-woman and even harbor some hatred toward them; that would be hostile sexism. It’s not that many people who are open about it, although more than you might expect actually these days.

And then there’s something called benevolent sexism. This is the sexism that’s harder to see. This is the sexism that actually a lot of women ascribe to because they’re socialized to it, which is “Oh, there’s just difference. There’s role-complementarity; you know, men are the strong ones and women are the sweet nurturing ones.” And they kind of, on the surface, glorify woman. They’re ‘my better half’. They’re the sweet ones and are self-sacrificing. They’re more sensitive. They’re more noble. But that’s what allows women to buy into their subjugation, right? It’s like, “Ok then if you pay for me and you support me, well I guess I’m getting a good deal? Even though, of course, the fact that I’m not allowed to earn more money….”

In the past women couldn’t work. They couldn’t go to college. They couldn’t own their property. They didn’t own their own money! And so this whole system developed to make women think that they’re being taken care of and we honor women. This role was offered to women and it was a way that women could gain some self-esteem, feel worthy, feel noble, but is very very limited because they could only do it one way. The classic was Phyllis Schlafly, right? You know, she’s passed, so…did you see that great movie, Mrs. America, it was about her?

AA: Yeah, it’s fabulous. A lot of my listeners actually have backgrounds in conservative religion, so in some bubbles it’s still very much fifty years ago.

I come from the Mormon tradition, so everything that you just described about women being discouraged from even working outside the home and being passive and being the supporters– that’s current today for a lot of people that I know personally. It’s still very relevant.

KN: It is, and there’s nothing wrong with role complementarity if people intentionally choose it, right? I know some people, high powered women whose husbands stay at home and take care of the house and take care of the kids. So if people want to do role division, there’s nothing wrong with that at all, but it should be your authentic free choice, not because you’re forced into it. It should be something you want to do, not something you feel like you have to do or that you have no other choices.

One of the problems with that as well is, because of role complementarity, if you look at the workplace it’s considered traditionally masculine and the roles are masculine so women are forced to act like a traditional man in order to get ahead in the workplace, which is not good for anyone because a lot of the skills associated with the traditional feminine role–like interpersonal skills, being more understanding, facilitating compromise, of communication–those have actually shown to be more effective in the workplace. So the fact that we do this role specialization harms everyone because it limits the amount of choices we have to get the job done. Anyway, so that’s one form of sexism.

Modern sexism is basically the claim that sexism doesn’t exist. You know “Oh look, look women are going to graduate school more than men are. They’re getting more college degrees, therefore no sexism exists anymore. It’s equal.” That’s like modern racism as well. “Oh, it’s equal. It’s already equal. There’s nothing to complain about” and that actually stands in the way of you, the same with racism and sexism–a lot of these -isms are subconscious. What happens is we all grew up watching these movies, getting these images, having these subconscious understandings of what men are like and what women are like and these are unconscious filters that bias everything we perceive.

So there’s this research, for instance, that shows if that if two people look at two exact resumes–one from someone named Steve and one from someone named Susan, they have the same qualifications–they’re going to assume if it’s kind of vague, that Steve is more competent and more qualified and should get more money for the job. Now, if it’s made really explicit that Susan’s also very very qualified, what’s interesting is they dislike Susan because she’s so qualified. There’s still this perception that a really competent woman must not be very feminine or nurturing and therefore we don’t really like her because she must be the b-word or something like that. You can see that in politics; the women who are really competent, they’re disliked because people assume that you can’t be communal and agentic at the same time.

And again this really does harm everyone. Men who are sensitive or family men who are kind of open–they get ridiculed as well and they can’t succeed as much. So sexism still exists and it’s really often at the level of how we…at the filters we put on things we don’t even know are there. And that’s why it’s so important to call attention to it, including things like anger, or women feeling like they shouldn’t speak up because it’s unfeminine, unladylike to do it. That means that not only are we harming ourselves, it means people don’t get the benefit of our really often very useful opinions.

AA: Yes, absolutely. Okay, let’s take it in that direction too because I’d love you to talk specifically about anger as it pertains to women.

KN: I’m not talking as someone who’s an anger management expert, I’m actually talking as someone who gets angry pretty easily. If you knew my mother, you’d understand; it’s part of our genes. My anger trigger is fairly…you know, the trip wire is pretty sensitive. And what had happened is for many years I kind of tried to accept my anger, but it was something I was a little bit ashamed of. Here I am, a meditation teacher who gets angry… and then feeling that this is a part of myself that I needed to work on. I didn’t really embrace it as part of myself until I had this situation where someone I knew, was close to, turned out to be a sex predator, was doing really awful things with his employees. I got really angry about it and a lot of the women involved didn’t get angry about it. They couldn’t access their anger. And I really started realizing how anger is so useful. Anger is necessary in order to get things done, in order to focus our attention, in order to spur us toward action, to speak up, to do something, to make some change and that’s when I thought about Mama Bear. This is part of the mother-role as well; if someone insults my child or tries to harm them in some way, watch out! I’m going to be furious and that fury, that anger, that rage is actually an evolved emotion.

It evolved for a specific reason: that when there’s some harm or danger–and you can also consider some sort of really unjust situation as a danger–our natural reaction is to get angry. It does many good things. It focuses us on the problem. It energizes us. It allows us to be brave and it communicates that something is wrong, both to ourselves and other people. And those are real gifts. So anger is not a problem in and of itself. The fact that women aren’t allowed to get angry because it’s not seen as ladylike, that’s actually again part of the system–of course if we don’t get angry, we aren’t going to get angry at how we’re treated or get angry at injustice. Having said that, anger can be constructive or destructive, right? And of course we want it to be constructive and not destructive and the difference is actually quite simple. It’s simple to describe, it’s less simple to do, granted.

So sometimes we can’t do it, but in terms of, theoretically, the difference: destructive anger harms people, constructive anger protects people. So protecting your children is constructive anger; it’s serving a good purpose. The difference between constructive anger and destructive anger is also that constructive anger isn’t personal. You’re not aimed at a person, you aren’t blaming a person, you’re focused on the threat. This is unjust, the situation, or this behavior is a problem. I’m angry at the behavior. I’m angry at the situation. At the same time I realize that the person causing the situation or doing the behavior is still a human being.

Destructive anger is very personal. It’s like it’s aimed at you because you’re a bad person. It’s insulting, it’s aggressive, it’s threatening. And when it becomes personal then it’s more destructive because you’re harming the person as opposed to just preventing harm. Also, constructive anger isn’t ego reactive, right? It’s not about ‘my feelings have been harmed’. It’s just that this situation is unfair and needs to be stopped. A destructive anger often tends to be ego defensive. It’s kind of reactive. It’s not very clear.

So those are kind of the basic differences between constructive and destructive anger. Also there’s more clarity and this is the hard part. In order to have constructive anger we have to have some sort of clarity. We need some mindfulness or some perspective so that we can see the situation clearly. But with destructive anger, what happens is we often just get into a white rage, we get carried away by our emotions. There’s no perspective where we can even make the choice of how to express this sentiment–is it going to be in a constructive or destructive way–and that is difficult. So again, I say I’m not really good at it. I’m very good at apologizing. I’m getting better at it over time, but I tend to be reactive just by my wiring…but you know, I have something to work toward and I am getting better.

The big difference for me when this whole MeToo movement situation happened and I was really the only one who took charge and spoke up. I kind of closed this guy’s center down as I got down and prayed to my anger: Thank you. Thank you for making me brave. And I realized that that same energy that leads to my getting angry sometimes is also the thing that’s driven me to accomplish so much in my life. It’s actually a good thing. Yes, we want to harness it. That’s why it’s called “How to Harness Kindness.” We want to harness it, we don’t want it to control us. We want to try to direct it in a useful way, but that energy is actually a beautiful thing and if we suppress it we’re suppressing our life force energy. You know, really, it’s like a volcanic force. We want to harness it to create thermal dynamic electricity as opposed to just exploding everywhere if we can.

AA: Okay, could you walk us through a scenario? You could take one from your life or one of the ones that you wrote about in the book where, let’s say, in real time, you’re in a situation where someone does something harmful. What would you say in the moment? What could you do that harnesses that mama bear, whether it’s to protect someone else or to protect yourself and say ”that is not right” but in a way that respects their humanity, allows them to grow–so holds them accountable while still being kind. How do you do it?

we all grew up watching these movies, getting these images, having these subconscious understandings of what men are like and what women are like and these are unconscious filters that bias everything we perceive.

KN: Yeah, you know one of the tricky things is when people are just in the presence of anger they react–even if it’s not directed at them. And so you can’t totally control other people’s reactions. But what you can do is make sure it’s not personal that you aren’t using you-statements. You aren’t saying “You are doing this. You are wrong”. You can use I-statements; I’m upset. I don’t feel good about this. The situation is causing me problems. Certainly nothing insulting or really just avoiding all ‘you statements’ if possible. Just focusing on behaviors, just focus in on situations.

Saying ‘no’ quite firmly, if you can control that. It can be hard, and by the way, like I say, not everyone reacts well to it. They just want you to be sweet and nice and happy. But if you’re sweet and nice and happy then you’ll never be able to stand up for yourself. You need to be able to, you know, try to be as polite as possible. Try to use things that help acknowledge humanity. “I understand that from your point of view such and such.” “I could see the situation for you is difficult.” When you do that you’re humanizing the person, but can say “This is how it’s landing for me and this is why I’m really having difficulty with this.”

So the more you can do that, the better. The more you can humanize the other person while still standing really firm about “This is not going to work for me.” That’s one way to do that, it’s really about trying to keep the humanity of the person while still drawing your clear boundary about the situation or the behavior.

AA: Yeah, that’s fantastic. So I just finished my master’s thesis and it was on the Civil Rights Movement. So I did a lot of reading on nonviolence, the philosophy and of nonviolence, and this is exactly what that is, right?

KN: Exactly. I mean, that’s where I’m drawing this from, right? Martin Luther King or Gandhi…it’s not like they didn’t get angry at injustice. Of course they did! If you aren’t angry. you’re probably asleep. Anger wakes us up. But how you express it makes a difference and some people are more skillful than others. I actually don’t count myself as particularly skillful. I’m okay sometimes, but I’ve seen it done and I know that the more skillful I am the better it goes.

Suppressing one’s anger is actually not helpful to anyone because then also the other people… they don’t get called to the mat about their behavior and they’re going to keep on doing it. And a lot of people, especially when you point out their humanity, when you acknowledge their humanity, most people don’t want to harm others. Most people–I believe in my experience, not everyone, but most people–are pretty good and there’s usually a situational factor that has led them to act the way they’ve acted. So if you can acknowledge that, then that gives them more chance to make a change.

AA: That is beautiful, and it is what I believe.

KN: Also, in terms of boundary drawing, a really important thing (especially for a woman) is not caring whether or not people like you. Because they do like you better if you say ‘yes’. That is not an illusion–they really would prefer that you subordinate yourself to them and do everything they want to do. And they may not like you as much. So that’s where self-compassion comes in. Your worth has to be Intrinsic. It’s like “It’ll be great if you like me, but if you don’t that’s okay too. What’s really important is that I respect myself. That I like myself. That I’m going to make decisions that are authentic for me.” And then your true friends will like you, but the ones who just want to use you or get something out of you, they may like you a little less and they may turn to someone else and that’s okay.

AA: Oh it’s so hard, that is so much easier said than done, don’t you think, especially in close relationships?

KN: Yeah, it is easier said than done, but I tell you self-compassion really helps. Because what self-compassion is, at its core, is a recognition of your intrinsic worth and your intrinsic rights as a human being. You don’t need other people to like you to be worthy. You don’t need to succeed. You don’t need to get it right to be worthy. Your worthiness is an intrinsic feature of being a human being. And then your own attitude toward yourself–your own respect, your own kindness, your own support, your own acceptance is actually the one that’s going to be most powerful.

Again, it doesn’t mean that we don’t want other people to like us, that we don’t care about other people–of course we do!–but our worth can’t be contingent on it because once it becomes contingent then we start making decisions that aren’t true for us and then we may say ‘yes’ and we get burnt out or we compromise in a way that somehow damages our integrity.

AA: Yeah, I’m specifically thinking about the anecdote that you wrote about a mother and a daughter, and I think the mother would often make comments about her adult daughter’s parenting (so the grandchild) and the adult daughter would just get so upset at her mom, but not say anything. And then, maybe it was at Thanksgiving dinner that she just lost it and swore at her mom at the dinner table and then learned how to–next time her mom did it–say “It’s not appropriate for you to talk about my parenting that way.” So she harnessed the Mama Bear energy for herself and said you can’t talk to me like that and that’s harming our relationship. And I thought Oh boy, it’s just so helpful to have that spelled out because again, I think sometimes it’s…

I guess there are different hard things doing it with an institution or with the boss or with your mom or with your spouse. There’s different hard things about each situation, but sometimes it’s those intimate relationships, especially if you’ve established a pattern in the relationship and then you change to stand up for yourself. Oh boy, it can be hard to tolerate that change in the dynamic, right?

KN: Yeah, it can. It can be hard for everyone and I think the more explaining you do, the more you really honor the other person’s humanity, honor the fact that they want to do what’s right, that they actually want to have a good relationship, they don’t want to overstep boundaries, they’re probably not realizing what they’re doing and the impact they have on you…then you know it’s still going to be messy, but it’s a lot more workable. The other approach, which is just to bottle…it usually doesn’t work either, right? Because then you just end up exploding at some point, or exploding the relationship–you just distance yourself from someone and then you can’t be intimate with them. It’s very hard to be intimate if you aren’t authentic. Authenticity and intimacy go hand in hand.

AA: Oof yeah, this is high level stuff. I mean, and again it’s harder to implement, but so important. Another kind of visual image that I took away from the book was the Hindu goddess Kali, and I loved that. Can you tell us about her?

KN: Yes, Kali. It’s interesting because a lot of the metaphors we have for these kind of powerful sources of rage are actually feminine, whether it’s a mama bear or, in Hinduism, it’s Kali.

So she is considered a goddess of destruction. If you look at pictures of her she has many arms and she’s holding a bunch of severed heads. At first it just seems like oh my god, this is horrible. But then when you understand, metaphorically, the head she’s severing is the ego. And so that rage is actually force to see through illusion, to see through the illusion of our separation. We think we’re all so separate when, in fact, we’re really part of a larger whole. This is actually a force for good when it’s targeted, right? So you might say if she cuts through the illusion of separation.

Usually anger dehumanizes others, you’re creating more separation. So if anger can be harnessed in a way to create connection…now, again, it is difficult so I’m not going to pretend it’s not. And again, people react to just the physical presence of anger–often they get frightened, and so the more you’re able to speak in a way that doesn’t frighten other people (which is, you know, you can have anger there but kind of control firmness) the better everyone reacts. Again, it is hard to do.

I’ve actually got an image of her and put her over my meditation cushion because I realized that, for me, I needed to stop shaming myself for my anger. And also, the more we allow ourselves to feel it internally, the more we accept it, the more we allow it to flow as an energy in our body as opposed to trying to bottle it or cork it, actually the more it can dissipate and process. Then we do have more of a chance to speak in a way that’s not so infused with anger that other people get scared. It really has to start with us, I believe, and really saying “Thank you so much, anger, for trying to protect me and standing up for me and giving me energy and giving me courage. I really appreciate you.” Then it’s a little easier to work with it as opposed to having it overtake you.

AA: Yeah, that’s fantastic. Another chapter that I wanted to talk about was the chapter on equality in the workplace and I was really humbled when I realized my own internalized sexism. You talked earlier about how you know if you see a resume, for example, two identical resumes–one has a man’s name, one has a woman’s name–you talked about how we perceive the man’s resume as that he’s more competent and qualified for the job and more likable. And there was a specific piece, a more specific study that talked about women being self-promoting versus men being self-promoting and I was really struck when you pointed out that, when a woman is self-promoting (for example, if she says like “Hey I’m doing this workshop, sign up. It’s this much money” or “Hey, my book was just mentioned in the New York Times. Isn’t that fun and exciting?” So she says something that celebrates her own accomplishment) that women are harder on that woman than men are. I thought, I’m guilty! I think I’m guilty of that and I wondered why? I really sat with that for a long time, why I have a very visceral negative reaction when I feel like a woman…and I’m trying to figure out what is the line? Because I can really rejoice with my friends for their accomplishments, I don’t get jealous really, but it kind of…there’s a threshold that it crosses and then suddenly hate it. And I don’t know why, but I’m really glad that you pointed it out so I can work with it in myself. I wasn’t proud of that at all.

KN: Yeah, thing is we don’t choose to have these biases right? We internalize them unconsciously from all the movies we watch from all the books we’ve read–just a lifetime of getting this from the larger culture. So a really good thing to do is just ask yourself “Would I react the same way if this were a man?” Maybe you would, you know? It’s not always gender, but sometimes you wouldn’t.

Again, what’s happening is because we have these idealized images of what a man is supposed to be like, of what a woman’s supposed to be like. Again these are subconscious, but the man is smart, competent, aggressive, go-getter, competitive, has that winning spirit, very agentic, gets things done. And the woman is self-sacrificing, she’s nurturing, she’s warm, she’s sweet, she’s a great mother, she just always puts other people first. These are idealized images, so when a woman shows qualities that are associated with the idealized man, we think Oh, she’s like a man, she’s not like a woman, so I don’t like her as much. Because she’s self-promoting she certainly can’t be self-sacrificing. And with men it’s kind of the opposite. With men it’s not so much that we dislike self-sacrificing men, but we don’t like weak men because women are supposed to be the weaker sex. The word ‘sissy’, for instance, is a real insult. You’re like a girl, you do it like a girl. “Like a girl” is an insult because they’re weaker, they have less status in society and that’s really why we don’t like men who show more traditionally female traits.

The whole thing’s really messed up, so you just have to question it. Would I be upset if it were a man? Would I be upset if it were a woman? Is anything really a problem here or is it just because somehow it’s triggering some idealized subconscious stereotypes of mine? And women are just as…if anything they’re worse offenders because in a way, subconsciously, you think Well, my book wasn’t mentioned in the New York Times, maybe that threatens my ego, but I’m such a good mother, I’m not writing a book. All this stuff goes on unconsciously, so we’re kind of threatened as well.

AA: Yeah, I was just thinking that exact same thing. I think sometimes people get threatened by people who don’t keep the rules, and when women are conditioned and socialized to be self-sacrificing…Maybe maybe I had a dream of being a doctor, but I was told “That’s not compatible with family life.” So I thought, Well I’m going to be noble, I’ll sacrifice. I’ll either not get an education at all or maybe I’ll do something totally different. I made that sacrifice. And then if I see a woman who doesn’t keep that rule and they didn’t make that sacrifice and they go ahead and be a doctor and then they’re promoting their career and they’re going for it.

I think that’s what I’ve observed sometimes in female relationships, is women who really that bottled up resentment. They think Well then all of you have to do this too. We all have to jump off this cliff together or it’s not fair. It’s not fair for you to do that. It really pits women against each other, sometimes.

KN: Exactly. The good thing about the research though is that if you integrate what this woman named Joan Hastings calls ‘Gender Judo’–in other words, if you try to show both. So a woman who’s maybe really competent, maybe she talks about “Yeah, my work got mentioned by the New York Times. Isn’t that great?” but then also intentionally says something more traditionally nurturing like “How’s your family? Tell me about it?” or something like that, then people… because what’s happening is that the more traditionally feminine role isn’t being so threatened. So here she also has that side, then I can like her.

You know no men don’t have to do that. We like men, we like men either way. We don’t like men who are traditionally feminine and have no masculinity, but…is that true? Yeah, that’s true, but women especially benefit from having both in balance and displaying it. So that’s one thing if you are a kind of go-getting woman that if you integrate both. It does help what’s called backlash– that’s a term for it when other people don’t like you because you’re breaking gender stereotypes. And it helps if you try to display both publicly, put effort into it.

“Like a girl” is an insult because they’re weaker, they have less status in society…

AA: Okay, so one last question while we’re on this about women in the workplace, but I think this applies really broadly in lots of different situations. You talk about having a strong back and a soft front–which I also thought was just lovely, such a good helpful image–and then you listed a few strategies for when we find ourselves in situations where a man, a person who does happen to be a man so it’s kind of a patriarchal situation, does something that is still unfortunately a typical power move.

I do really try to give the benefit of the doubt. That’s really important to me. So I’m thinking, let’s say I’m in a meeting at work or class at school or whatever and the classic thing happens where I say an idea and it doesn’t get acknowledged and then two minutes later a man says it, claims that it was his thought, claim the origin of the idea, and then it gets praised and it takes off and I’m sitting there just burning inside, going “Do I say something and seem like a jerk or do I sit here and then that’s being complicit?” What do we do in a situation like that that shows fierceness, but also compassion and kindness?

KN: Yeah, that’s great. Just to acknowledge, the phrase “soft front, strong back” is Joan Halifax and then the woman who talks about…she’s got a great term for it, it’s Jessica (I’m blanking on her last name right now) but she calls it the ‘bro-priator’. It’s a man who appropriates a woman’s idea. And yeah, you absolutely need to speak up. You can say “Oh, so glad you liked my idea. That’s wonderful!” So basically instead of saying “Hey, you stole my idea.” You can say “Oh I’m so glad you all like my idea. Thank you for validating that, John” or whatever. So trying to kind of go with the flow. Also the ‘man-terruptor’ is the other one, the ‘bro-prietor’ and the ‘man-terrupter’. Women get interrupted a lot more often, but you need to speak up because if you don’t speak up you will just get bowled over. But you can do it in a way that’s kind of friendly or funny or positive as opposed to just super, confrontational so that there’s less backlash when you do it that way.

We have to speak up, not just for ourselves, but for everyone else because if we don’t speak up it will keep on going. It’s like the MeToo movement; a man can’t get away with it now. Some do, but it’s a lot harder for men to get away with sexual harassment and abuse in the workplace, and it used to be because there are no real consequences and if women had not been willing to stand up and say “We are not going to take this anymore.” things would still be the same. So that’s why we speak up for each other. We really need to speak up so we can make change.

AA: I have to say yes, absolutely and I’ve been so pleased the past year with a few different pieces of media. The movie The Duel with Ben Affleck and Matt Damon talking about this and it takes place in the middle ages, but it’s about sexual assault and it shows it from all different people’s point of view. And then The Morning Show which was a series (where I don’t know if you saw it) but watching Steve Carell’s character in that–and listeners if you haven’t seen it, it’s really worth watching because watching Steve Carell’s character go from (and sorry this is a spoiler) but he does commit a really horrific sexual assault and he really didn’t think he did at the beginning. He really didn’t see anything wrong with his behavior, precisely to your point Kristen, that if you don’t call people to the mat, if you don’t call people to account, they can go on sometimes really not realizing they’ve done anything wrong. And so if we speak up it can change that individual and it can change the culture and there’s a really meaningful arc in that show where he realizes the impact that he made.

I’m just so gratified and pleased to see that the cultural conversation is happening and that that story is popping up in lots of different avenues to call men to account and say “Hey, you know, the way your dad did it…” I’m really happy to see that progress being made right in front of our eyes.

KN: Yeah I was actually, believe it or not, at a meditation retreat and the teacher showed a film (it wasn’t a silent retreat) and he didn’t even realize that in the film the women were just arm candy. It was all about the man. The women had very tiny roles and they were only the sexy love objects. I actually raised my hand in front of the whole group and I said “Did you realize that movie (it was an older movie, but still) had demeaning images of women?” And he said “No, I didn’t even notice.” You know you have to be brave and I had so many people come up to me and say “Thank you so much for saying something.” No one wanted to say anything; it was the teacher’s favorite movie, but he wouldn’t have even realized if I hadn’t pointed it out. And I said it very nicely and kindly and not in a confrontational way. Otherwise nothing will change.

AA: Wow. I agree.

Dr. Kristen Neff I am so grateful for the time that you spent with us today. I learned so much. Again for listeners, Dr. Neff’s book is called Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim their Power, and Thrive. I can’t recommend it highly enough, and I’m just so grateful that you joined us on Breaking Down Patriarchy today. Thanks so much.

KN: Thanks so much. It’s been a lot of fun.

We have to speak up,

not just for ourselves, but for everyone.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!