“Mary’s goodness is presented as the precise antidote to the evil of Eve”

Amy is joined by Sophie Allebest to discuss multiple texts about the early Christian conception of the Virgen Mary, the veneration of women, and attempt to fill in critical historical gaps.

Our Guest

Sophie Allebest

Sophie Allebest is first and foremost, a Pisces. She loves Art, Architecture, History, and rainy days. She enjoys the ancient art of rhetoric and debate (i.e., arguing), and swimming in a freezing ocean or pool. When she’s not working hard at school and art, Sophie loves spending time with her family, friends, and cat.

The Books

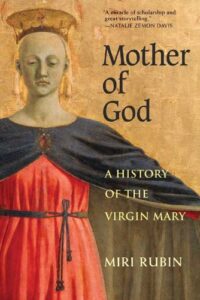

Mary, Mother of God:

A History of the Virgin Mary

by Miri Rubin

How did the Virgin Mary, about whom very little is said in the Gospels, become one of the most powerful and complex religious figures in the world? To arrive at the answers to this far-reaching question, one of our foremost medieval historians, Miri Rubin, investigates the ideas, practices, and images that have developed around the figure of Mary from the earliest decades of Christianity to around the year 1600. Drawing on an extraordinarily wide range of sources—including music, poetry, theology, art, scripture, and miracle tales—Rubin reveals how Mary became so embedded in our culture that it is impossible to conceive of Western history without her.

Miri Rubin is Professor of Medieval and Early Modern History at Queen Mary, University of London, where she specializes in European history between the eleventh and sixteenth-centuries.

She is the author of, most recently, Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary (2009), The Hollow Crown: A History of Britain in the Late Middle Ages (2005) and The Middle Ages: A Very Short Introduction (2014). She has made numerous media appearances including the radio programs In Our Time and Making History for BBC Radio 4.

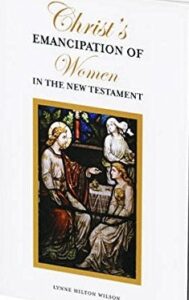

Christ’s Emancipation of Women

in the New Testament

by Lynne Wilson

In order to appreciate the dramatic change that Jesus made to the role of women, this book places Jesus’ teachings in the context of Judeo-Greco-Roman family life of the day.

What was day-to-day life really like for women during New Testament times? ~How did Christ’s teachings and example come into conflict with societal norms for women at the time? ~How can we make sense of some of the seemingly sexist teachings of Paul? ~What role did faithful women play in building up the early church?

Lynne Hilton Wilson is a wife, mother, scholar, teacher, and author.

She was an adjunct professor at BYU and is an institute director and teacher at the Stanford-Menlo Park Stake Institute of Religion. She has been a volunteer in the Church Educational System in France, Belgium, and Wisconsin. She is also a popular speaker and lecturer. She has written three books, including Christ’s Emancipation of Women in the New Testament. She is a research fellow for BYU Studies, the Maxwell Institute, and Interpreter.

Alone of All Her Sex:

The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary

by Marina Warner

Devoting different sections of the book to each of the various roles Mary has assumed – Virgin, Queen, Bride, Mother, Intercessor – and drawing on official dogma, folk legend, art, history, literature and psychology, Marina Warner shows how the figure of Mary has shaped and been shaped by changing social and historical circumstances from the first century to the present day, and why, for all their beauty and power (and indeed because of them), the legends of Virgin Mary have condemned real women to perpetual inferiority

Novelist, critic and cultural historian Marina Warner was born in London on 9 November 1946 to an English father and an Italian mother. She was educated in Cairo, Brussels and England, and read French and Italian at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. She was Professor in the Department of Literature, Film and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex from 2004 to 2014. She is currently Professor of English and Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London.

She is the author of a number of works of fiction and non-fiction, including critical studies, novels and children’s books.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: During our last two episodes, Sherri Crawford and I discussed Gerda Lerner’s The Creation of Patriarchy, and we talked about structural patriarchy in the ancient world, including in the Bible. Just a couple of days after we recorded those episodes, some dear friends of mine and my husband had their first baby, a little boy. They’re Jewish, and we were invited to the bris. I could not believe the timing. The very week I had talked about circumcision on the podcast, what we had called the penis covenant, I was going to witness a bris, which is a ritual circumcision, and in Hebrew means covenant. I logged on to Zoom; this podcast was recorded during the COVID pandemic, so everything is virtual right now. And their family and friends were gathered all over the world on a Zoom call, and I saw our friends there with their new baby and their family and their rabbi, and my heart was so full. I was immediately emotional. I have a deep love for these friends and also a deep affinity for Judaism due to having had Jewish friends my whole life and being a guest at many different Jewish ceremonies throughout my life, and they’re always really moving for me.

And Sherri and I met because we were both studying in Israel for five months during college and we both took Hebrew language and history of the Jewish people. And of course, because of our shared book of scripture, I’ve always felt like we are spiritual cousins along with other sects of Christianity and with Islam who are known as the other peoples of the book. But because we had just read Gerda Lerner’s book—and Gerda Lerner, by the way, was also Jewish and I think actually part of her project was confronting the male supremacy in her own religious tradition—because we had just recorded that episode, I had all of those parts of the Bible that excluded women fresh in my mind. And so parts of the bris were really hard for me. It was hard for me that the ceremony was really, truly a continuation of the Abrahamic covenant, which is a special bond between a male father god and his male prophet, and that man’s son, and that man’s son, and that man’s son, all the way down. through the sons of Israel, like we talked about on that last episode.

I know that Jewish heritage is traced through the mother, and that is really lovely, and Christians don’t have that matrilineality. But the covenant with God is through the men, and the token was in the flesh of the male organ, physically, by definition, excluding people who are biologically female. And there’s no counterpart for the girls. There’s no ceremony named after a matriarch where girls are brought into a covenant with a mother god. It was really hard for me when they referred to any of the scriptures because all the stories were about men, written by men, written for men. And I felt the way I often feel in my own religious heritage, just completely left out. I just felt marginal in a spectator role as a woman, while God does the important stuff with his favorite children, the boys. But it was also so beautiful. The way this family practices Judaism did include the women. The grandma held the baby’s hands while he was circumcised and whispered in his ear and comforted him. The baby’s mother and the baby’s father took turns speaking. And by the way, the baby’s mother. Is one of the most educated, most accomplished, most powerful women I know. And the baby’s grandparents and his aunts and uncles, both men and women spoke. And also the gown, the baby wore had been worn by grandfathers and uncles, but also by his mother, our friend and by her sister at their naming ceremonies, the blessings and hopes and wishes and desires for peace and strength and joy and renewal were so exquisitely beautiful that it makes me emotional to remember them even right now. I bawled my eyes out through the whole thing when the rabbi wrapped our friends up with their baby in a tallit or prayer shawl, I felt like my heart was going to explode the love of that mother and father for each other and for their baby and the connection with their ancestors and their faith tradition and that language and the community that they had so generously expanded to make me a part of welcoming that baby into the world was so, so beautiful.

And yet it was still hard for me. And I share this because this experience of having those two experiences right next to each other, recording that episode on the creation of patriarchy, and then participating in that beautiful religious ceremony just kind of showed me how complicated all of this is. There’s joy tangled up with pain. There’s beauty tangled up with hurt. And as I try to untangle those elements of history and religion and human psychology, I want to be able to confront difficult and problematic aspects of culture in order to improve life for everyone. But as I identify those problems, I don’t want to lose my bearings. I don’t want to become a cynic whose vision is filtered through dark, pessimistic, ill-tempered lenses. And above all, I never, ever want to hurt anyone. I want to keep seeing the beauty and to keep believing the best in people. So I guess… I wanted to start with that today because I want to make kind of a declaration of the ethos of this whole project: I want to be honest and critical about systems, but I want to be careful and tender with human beings. And that’s specifically the needle that we will try to thread today, again, as we talk about complexity and religious belief on this next step of our historical timeline.

So we just left off with the Hebrews and the Greeks in the creation of patriarchy, and when we pick up the next episode, we’re going to begin with the creation of feminist consciousness, which starts with a little bit about the early church fathers and then goes on to women’s writings in the Middle Ages, so there’s a historical gap. And on this bonus episode, my reading partner and I are going to fill in that gap with a few important aspects of early Christianity focusing especially on the Virgin Mary. This is another topic that is precious to many people, including us, and we will try to be both honest and gentle in our analysis. We’ve gleaned this information, by the way, from a few different books rather than just one essential text. And so all our sources are published in the show notes on our website, breakingdownpatriarchy.com. So with that long introduction, let’s get started. And first I’d like to introduce my reading partner for today, Sophie Allebest.

Hi, Sophie.

Sophie Allebest: Hi.

AA: You may have noticed from the last name that Sophie and I are related. She is my third daughter and she is currently in high school. And I believe, Sophie, this makes you the youngest reading partner on our lineup. I’ve tried to invite women of all different ages and different backgrounds and different races and ethnicities and sexual orientations and, yes, Sophie, I think you are our youngest.

So Sophie loves everything having to do with art and history and art history and poetry and philosophy. And while our whole family is really into all of those subjects as well, Sophie, I feel like you are definitely our resident expert on art history and that will come in really handy today. Your insights will really be a valuable asset as we discuss, especially the Virgin Mary so I’m really, really happy you’re here.

SA: Thanks for having me.

AA: I also like to ask my reading partners what interested them in the podcast project. I know you’ve been hearing about it every day for months. So maybe just tell us what interested you in this specific topic.

SA: Okay. Well, I was really interested in this topic because it touches on a lot of the subjects that I love the most. I get to learn about women’s history, which I learn a lot less about in school. This project gives me a closer connection to the people and especially the women who came before me. And in this episode, we’re going to be talking about some of the different ways Mary was depicted in art, and that’s something that I love learning about. Art does so much more than look beautiful, which is still important to me, but it also lends itself to psychological analysis. Looking for the details in the art and what those details say about the artist’s intentions is really rewarding for me. Art is really a reflection of the artist and the artist’s environment. So with a painting or a sculpture, you get a good idea of the world at the time and how certain subjects were viewed. And we’re obviously going to talk about religion, which is another thing that brings me so much joy to talk about. I find it fascinating to look at what religion comes from in the society, and why it formed the way it did, and then ask the question, ‘What does that say about that society?’ And then it’s interesting to me to see how that exact religion goes on to impact the people and the government.

Thanks for inviting me, mom.

AA: Oh, thank you so much for being here. That introduction was fantastic and just confirms what I thought that you would be such a great reading partner on this episode.

I’m really excited. For today’s episode, we’re going to talk briefly about four concepts. First, we’ll talk about Christian views on women as presented in the New Testament of the Bible. Second, we’ll talk about the early Christian church and the Virgin Mary. Third, we’ll talk about convents and the lives of nuns. And fourth, we’ll talk about the Protestant Reformation and its impact on women. Does that sound good?

SA: Sounds good.

AA: Okay, so the first concept is the figure of Jesus Christ in the Christian Gospels. One book I read on this topic is Christ’s Emancipation of Women in the New Testament by Lynn Wilson. The thesis of her book is that Jesus’s behaviors and message are very pro woman and it even liberating, especially in the context of gender depression in which they lived.

with a painting or a sculpture, you get a good idea of the world at the time and how certain subjects were viewed

She points out that Jesus is a revolutionary figure, like in John 4:7 and John 5:30 he initiates conversations with women, which was strongly discouraged at the time. In Luke 10, he includes them publicly as his students and disciples. In the book of Mark he allows a menstruating woman to touch him, which was completely inappropriate and a violation of the social norms and actually quite scandalous at the time. In Matthew 28, he appears first to women after his resurrection or rather to a woman, to Mary Magdalene thus entrusting her with the role of a witness. And actually, a Catholic friend pointed out to me once, if you define the Christian church as the people who are witnesses of Christ’s divinity, then for those hours after Mary Magdalene saw the resurrected Jesus and before she told the disciples, Mary Magdalene was the entirety of the Christian church. She was the only one who knew. And of course, another aspect of the Christian Gospels that elevated women was the fact that a human woman, Mary, was entrusted with being the mother of the son of God.

SA: Yeah, and Jesus never tells women to get back home into their proper place, and all of his teachings are for everyone. Everyone is supposed to be as wise as serpents, the women too, and as gentle as doves, the men too. He doesn’t say that men should be strong and women humble. He says that all human beings should be both strong and humble. He doesn’t make gender distinctions.

AA: Exactly. So I really loved Lynn Wilson’s book and really highly recommend it, especially for any listeners who are believing Christians. I found it really insightful and she does a great job giving context to reading those familiar passages, but in the context of history and what was going on at the time.

But then in the New Testament, of course, after the gospels, then you have Paul. So he is definitely a shift in attitude. He’s definitely grounded in sexist tradition. He never actually met Jesus and only converted after Jesus had died. So he never observed how Jesus behaved with women. I don’t know if that would have helped anyway, but he definitely had a different attitude toward women than Jesus did. And maybe it would have helped him to see how radically inclusive Jesus had been. But in any case, here are some thoughts from Paul about women. This is from first Corinthians 11:3-6 in the New Inspired Version of the Bible. It says, “but I want you to realize that the head of every man is Christ and the head of the woman is man. And the head of Christ is God. Every man who prays or prophesies with his head covered dishonors his head, but every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head. It is the same as having her head shaved, for if a woman does not cover her head she might as well have her hair cut off.” So obviously this is talking about women having their hair covered, that modesty and not covering her hair is important, but for me the most important part of that is saying that the head of the woman is man.

Sophie, will you read the next scripture?

SA: Yep. This is from the book of Ephesians 5:22-24. “Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, as Christ is the head of the church, his body of which he is the Savior. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit to their husbands in everything.” I’m wondering if there’s a correlation between churches that emphasize submitting to God and churches that tell women to submit to men. Do churches that encourage having a more familiar relationship with God rather than bowing down and submitting also have more gender equality?

AA: That is a really great question. I think it makes sense that a worldview that emphasizes hierarchies probably starts with God to men and then passes down the chain. That seems like a really familiar phenomenon with lots of different religious structures. And I’m thinking how the word ‘Islam’ literally means ‘submission’. As in submission to God, and that would be really interesting to analyze, but at the same time, I’m also thinking about Buddhism and how Buddhism doesn’t emphasize submission to an all-powerful deity the way that Islam and Judaism and Christianity do. It’s more about individual mindfulness, but then one of the Buddhist sacred texts that I read in school had a lot of sexist stuff in it. So I don’t know. I mean, every religious text I’ve read has a bunch of disappointingly sexist stuff in it. So it’s true….

I don’t know. That’s such a good question. I know you and I’ve been talking about Quakers a lot lately and that. That would be interesting to explore, but maybe we should ask that question. That’s such a fantastic question for when we expand the project to other traditions, which I do intend to do, but that’s a really interesting question. So shall we go on? Would you mind reading the next one?

SA: It’s 1 Corinthians 14:34-35. “Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak but must be in submission as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home, for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.”

AA: Okay, I have to throw in here that one time, years ago, I was sitting in an all-women’s church meeting, And the teacher was teaching a lesson on something that got kind of complicated—I don’t remember what it was, but there’s a pretty lively discussion of a scriptural passage or something—and a woman behind me got flustered and just called out, “This is too complicated. Let’s just go home and ask our husbands.”

SA: Oh boy.

AA: I know. Right. My head whipped around. I was like, what? And it was a young married woman. She was in her early twenties. I have never forgotten that. I had never heard… Thank goodness, right? I had never heard it articulated that clearly. But yep. I don’t know if she got that from the culture or from reading that scripture, but there it is right in the Bible. And there it was being played out in real life in real time.

Okay. One last quote from Paul, and this is from first Timothy 2:11-15. “A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man. She must be quiet, for Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived, it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing if they continue in faith, love, and holiness with propriety.” So, from all of these passages of scripture, we can see that Paul’s views on women are firmly rooted in the biblical story of Eve, which we talked about on our last episode. And he emphasizes the version of Genesis, wherein Eve was formed second after Adam, which he says gives her lower status. Paul emphasizes her sin and bringing Adam into sin, and he says her only redemption is by bearing children. And he assigns all of Eve’s guilt to women in general and, due to that guilt, he makes rules about what women can and can’t do. They have to cover their heads in shame. Wives have to submit to their husbands. In general, women have to submit to men and never have authority over men. Not because they should be equal, but because men actually should, in fact, have authority over women. Women can’t speak in church, they should always be quiet, and always be in full submission.

All of these opinions and interpretations, in my view, are a huge departure from the teachings of Jesus Christ. And yet, they got compiled in the same book of scripture with the gospels. And so millions upon millions of people have regarded Paul’s words as also the word of God. And they think of these passages also as God’s law and God’s will. And actually, if you want to read a really great book about what it means to live by the little literal words of the Bible as a woman, you should read a book by Rachel Held Evans. It’s called A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a liberated woman found herself sitting on her roof, covering her head and calling her husband master. Evans is a believing Christian, but she points out some really big problems with a literal reading of the Bible, and she does it in a really funny, really smart way.

Okay, so that’s all I have for the New Testament passages. And so now we’ll go on to talk about the early Christian Church and the Virgin Mary.

SA: I started by looking on the website Encyclopedia Britannica, and the first thing that I found interesting was this sentence. “Because of the influence of Plato and Aristotle on those who developed it, Roman Catholic doctrine must be studied philosophically even to understand its theological vocabulary.” It’s good to keep in mind that early Christianity was heavily influenced by the ancient Greeks. That’s really important when we think about how people viewed women.

AA: Yeah, totally. And actually something I thought of too, I will never forget this moment in my first quarter of my master’s degree when the professor was talking about the influence of ancient Rome on the early church. And he said that the papacy and the Catholic Church’s hierarchy was organized in the same way that the Roman empire’s military had been organized.

SA: Wow.

AA: I know. I like nearly fell out of my chair. I think I actually physically did put my head down on my desk.

SA: Yeah. What?

AA: So there were lots of influences on Christianity, especially from the classical world, like you just said, and they were all extremely androcentric— ‘andro’ meaning man, of course—androcentric patriarchal structures.

SA: So yeah, that makes sense, but then is also still quite surprising.

AA: Yeah, that’s how I felt.

SA: Okay. So back to church history, a basic timeline goes something like this. According to Catholic tradition, the Catholic Church was founded by Jesus Christ, and it’s a continuation of the early Christian community established by the disciples of Jesus. Catholics believe that St. Peter was Rome’s first bishop. St. Peter was the one who was appointed to be the head of the church by Jesus Christ himself and is always depicted in art holding keys because he received the keys to the kingdom of heaven from Jesus. After Jesus death, he ministered in Rome in the 1st century AD, and so that became the headquarters of the church.

Then St. Peter consecrated Linus as the next bishop, or pope, and that started the unbroken line all the way to the current pope, Pope Francis. By the end of the 2nd century, bishops began congregating in regional synods, which means a church council, to resolve questions about doctrine and policy. Jesus apostles gained converts in Jewish communities around the Mediterranean Sea, and over forty Christian communities have been established by 100. Although most of these were in the Roman Empire, notable Christian communities were also established in Armenia, Iran, and along the Indian Malabar coast. The new religion was most successful in urban areas, spreading first among slaves and people of low social standing, and then among aristocratic women. I wonder if that’s because of Jesus’ message of elevating the poor and elevating women’s status, or if it’s because the lives of the people who are struggling are really hard and they have a greater need for stories that will comfort them and give meaning to their lives or give them something better to hope for after this life is over.

AA: Yeah, I’ve wondered the same thing and I actually noticed that when I was a missionary in Chile, the church message that we were preaching was also really received well by women and people who were struggling with poverty, actually. So I think that’s fairly common.

SA: I remember learning about that in my unit on Rome in seventh grade. We were talking about how Christianity, about that exact thing, how Christianity became much more popular with poor people for both reasons: elevated them in their everyday life and also the promise of ‘oh my suffering now isn’t the end for me’, right? I can still have an opportunity to live like the richest people when I die.

AA: Yeah, interesting.

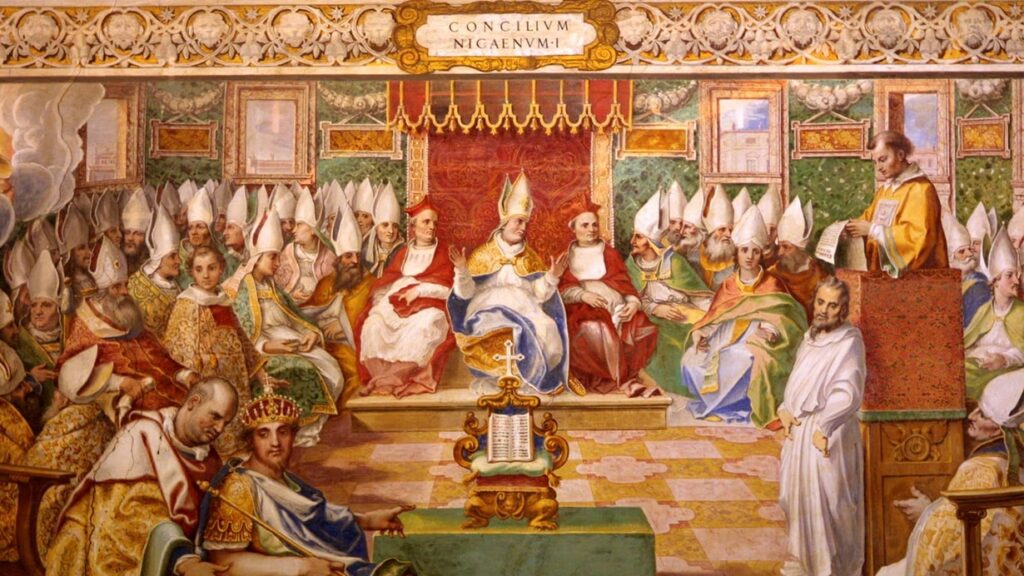

SA: Christians were badly persecuted for a while. Estimates of the number of Christians who were executed ranges from a few hundred to 250,000. But then Constantine became emperor of the Western Roman Empire in 312, and he attributed his victory to the Christian god. So he issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which legalized Christianity. He held the Council of Nicaea in 325, when a group of church leaders (of course all of them men) met together and decided on official church doctrine, and in 380 Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire. There are lots and lots of popes and lots and lots of theologians to talk about St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine of Hippo, but I think you’re going to talk about their thoughts on women in your next episode, right?

AA: Right. Exactly.

SA: Okay, then we’ll just skip them for now and just talk about when Catholics began to pray to Mary. And this is a meaningful topic for me because I remember walking all around Spain with you when we lived there when I was little, doing kind of a treasure hunt of beautiful Catholic churches and seeing so many different amazing Mary statues and seeing one of the oldest paintings of the Virgin Mary in Italy last summer.

AA: Yeah, that was amazing.

SA: Thinking back, I’m not super surprised that my interests are what they are because I’ve been learning about art history and looking at beautiful Catholic churches since I was six. Okay, now back to the timeline. Catholics make a distinction between worship and veneration. They say that they don’t worship Mary, but they venerate her. The word ‘venerate’ comes from Latin and means ‘adore’ or ‘revere’, so they respect her and try and be like her, but they don’t worship her. Catholics claim that the roots of the veneration of Mary are found in the Bible. For example, she was, of course, made the mother of God through a miracle. One quote that I found in my research says, “The Virgin Mary began to cooperate in the plan of salvation from the moment she gave her consent to the incarnation of the Son of God.” And then Mary was there all the way through the end of Jesus’ life and played an important role according to Catholics. Particularly significant is Mary’s presence at the cross when she received from her dying son the charge to be mother to the beloved disciple. Catholics interpret that through that disciple, Christ is giving care of Mary to all Christians.

Mary had been venerated since very early. The first image of Mary is a painting of her in the Roman catacombs in the 2nd or 3rd century. Catacombs were underground burial places and tunnels for religious practices. It’s quite realistic the painting is, and different from the Mary art we’ll be discussing later. Though it’s kind of hard to make out, Jesus is holding on to Mary as she nurses him, unsurprisingly embodying the mother figure. It’s a very natural painting with human features and a tender feeling. And the oldest Marian prayer refers to her as ‘Teotokos’, which some interpret as ‘the mother of God’, but I’ve also seen as ‘God-bearer’, and I find that distinction interesting, the use of the word ‘mother’. I can’t tell if the phrase mother of God or God-bearer gives her more power or what that says about her identity. Both phrases make her identity completely dependent on her relationship to Jesus, but to me, mother implies a softness and God-bearer kind of implies strength. But anyway, it was finally declared a dogma in the church that Mary was the Mother of God at the Council of Ephesus in 431. This is interesting to me because she had been prayed to and painted for hundreds of years, but the first churches dedicated to Mary only start to appear after that event.

AA: Yeah, that is really interesting. That, like you just described, that these practices had been present among the people for a while, and then they were just formally dogmatized, made part of the official Catholic doctrine at those councils, and then you start to see things appearing with churches being dedicated to Mary after that, but that people were doing it already. They were already praying to her and they already had these beliefs in her as the mother of God. One thing I was thinking about also is from some books I read was that as the Catholic Church emphasized Mary’s role, she literally became known as the new Eve.

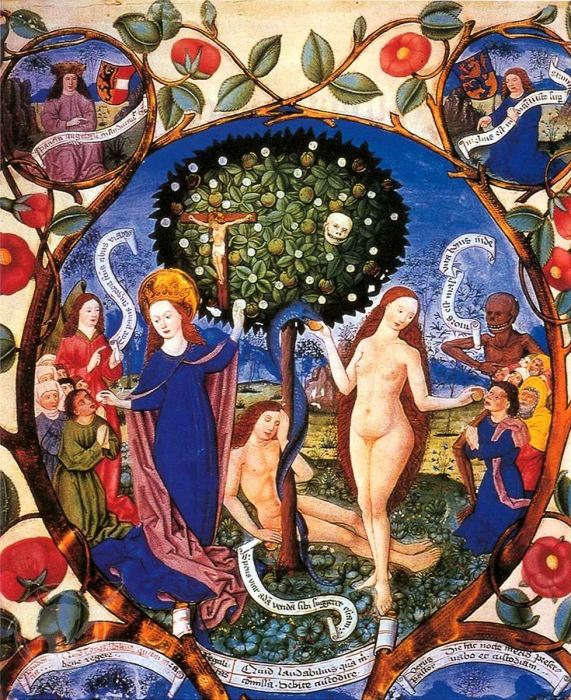

So Mary offered an alternative role model for women rather than Eve, and she offered potential redemption for females as a whole. As 2nd century cleric Irenaeus comments, “The knot of Eve’s disobedience was untied by Mary’s obedience. What the virgin Eve bound through her disbelief, Mary loosened by her faith.” And then St. Jerome echoes an even more concise slogan, “Life through Mary”. So they saw Eve’s negative acts as being canceled out by Mary’s positive ones, almost like a mathematical equation.

SA: Yes. It’s fascinating. And this theme is developed in the visual arts as well. One prime example of this is Berthold Furtmeyr’s 1489 work, The Tree of Life and Death Flanked by Eve and Mary-Ecclesia. In this vividly colorful, highly symbolic work, Furtmeyr places the iconic tree in the exact center and invites the viewer to toggle between the highly symmetrical left and right sides. On the right is a nude Eve, flanked by skeletal figures, and frozen in the act of accepting a forbidden fruit from the serpent, with one hand seemingly offering another wicked fruit to an unfortunate supplicant. On the left side, in a pose which perfectly mirrors that of Eve, is the chastely clad, halo-bearing figure of Mary, who is surrounded by a crucifix and an angel instead of skulls, and offers to her companions a sacramental wafer rather than the fruit of destruction. Mary’s goodness is presented as the precise antidote to the evil of Eve, counteracting its effects and providing a fresh start in a worthy example for women.

And this had a real effect on women’s lives. It really helped women to have a divine mother to look up to. In Mary Rubin’s book, Mother of God, she quotes a young mother named Aude Faure from the 12th century who wrote that when she was troubled by doubts about the Eucharist, her body and life in general, she was comforted and strengthened by a reflection on Mary. And even men liked having a heavenly mother figure to ask for help. Bernard of Clairvaux, who lived in France in the 1100s, said this, “In dangers, in doubts, in difficulties, think of Mary, call upon Mary. Let not her name depart from your lips, never suffer it to leave your heart. While invoking her, you shall never lose heart. So long as she is in your mind, you are safe from deception. While she holds your hands, you cannot fall. Under her protection, you have nothing to fear. If she walks before you, you shall not grow weary. If she shows you favor, you shall reach the goal.”

they don’t worship Mary, but they venerate her

AA: Amazing.

SA: And even beyond balancing out Eve in art, we start to see lots and lots of different types of Mary art. I’m going to talk about three major genres that present Mary in a role of importance. First is probably the most familiar, Mary in the role of the mother of God. As I mentioned earlier, there are really old paintings that depict Mary and Jesus in very human moments that any mother or child could relate to, but most of the time she’s portrayed in kind of a less personal way and more in the way you might typically think of: dressed in blue with her head bowed, holding the baby Jesus in her arms.

It’s quite rare for Christian artwork to have women as the most prominent figure in the painting, but in this type of work Mary is always the biggest figure. In fact, in some paintings, Mary is equal in size and stature to Joseph, and sometimes leads the Christ child by the hand, with Joseph following behind. Even in the paintings where it’s just Mary and Jesus as an adult, she clearly still holds the most power. It’s continuing a tradition of ancient goddess worship. This way of depicting Mary looks quite similar to sculptures of Isis and Horus in ancient Egypt.

The second genre is known as the Maria Regina, which in Latin means ‘Mary the Queen’. Regina means queen, and in English we have the word regal. In lots of paintings and mosaics Mary is shown reigning as the queen of heaven. With priests, saints, wise men, and in some paintings, even the pope worshipping at her feet. One of those paintings was done by Diego Velazquez in 1644. The scene is of Mary being crowned by both the Father and Jesus the Son, each holding a side of the crown above her head. The three figures form a triangle, but Mary is still the center of the piece. Her blue robes contrast the deep reds worn by the men above her, and she rests her hand over her heart as she looks down. Two Italian artists in the years 1340 and then in 1504 both painted this scene with very similar structures, but in Velázquez’s painting Mary and Jesus sit at the top of these paintings, Jesus being taller as Mary bows her head at him. Several angels and other figures are below and at the side, praising Jesus and Mary. Her hands are crossed over her chest or held in a prayer like motion that indicates reverence, gratitude, and humility. Mary looks meek compared to Jesus, and one of the only things that even lets you know that she’s important is the crown above her.

This is different from Velazquez’s painting where Mary is the biggest figure in the picture, the clear focal point. Her head is bowed down instead of at the men or man crowning her. Her posture is regal, her shoulders back and her hand laying over her own heart, almost pointing to herself. This painting would make just as much sense if there were no men in the painting. But it’s important to keep in mind that even though this art depicts Mary being crowned the Queen of Heaven, she is often depicted lowering her head or kneeling at her son’s feet to receive the crown from him. The implication of which is that the crown is both his to give and his to take away. In the Velázquez painting, the entire Holy Trinity still presides over the woman, the imposing bearded figures of God the Father and Jesus Christ bestowing the crown upon her from above.

And the third genre are hollow medieval statues known as virges ouvrantes. Sorry, I speak Spanish and not French.

AA: Me too. We’re going to do our best.

SA: But it’s French for opening virgins. These are figures of Mary that form an all-encompassing shell. You can think of them kind of like Russian nesting dolls, but there’s a door, and if you open it, you see that on the inside there are carvings and paintings of church leaders, and in some cases, depictions of God the Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit. That’s pretty incredible, and not exactly the way Mary was presented in the Bible. If you just saw those statues and didn’t know anything about the Bible, you might think the religion had a goddess that ruled over everything. One of these is from the year 1300 and has large amounts of gold covering Mary on the outside, and then the majority of the inside as well, even opened to reveal Jesus sitting with the cross, Mary’s crowned head remains visible. To me, she appears to be embodying the mother archetype again, but in a powerful way that is, again, reminiscent of more ancient goddess worship. Her power here is not being shown given to her, and almost looks like it’s the opposite of the coronation images, and this time she’s presiding over the people inside, including the men who are above her in most other works.

It’s not surprising that those Vue de Gouvernant statues actually came to be regarded by church authorities as misleading and inappropriate, visually ascribing too much primacy to the Mother of God, who was, after all, only a woman.

AA: Yeah, exactly. I mean, just thinking about those statues, it is kind of amazing. I keep thinking of like the song, “he’s got the whole world in his hands”, right? In this case, it looks like Mary’s got the whole world inside of her, including God, the father and Jesus Christ. So it’s not surprising that. Eventually, the Catholic Church was like, yeah, no, that’s a little too far. She is encompassing everything.

That was really brilliant analysis, Sophie. Thank you so much.

SA: Thanks mom.

AA: That was really awesome. The scriptural verses describing Mary refer to her submission, her dutiful compliance, and her passiveness as the male characters in the story perform. perform the heroic action. When she’s first introduced in the biblical narrative, which as we learned a couple of episodes ago was written a long time after these events happened, and was written of course by men, we know only that Mary “found favor with God.” That’s not a bad thing, of course. If we believe in God, then, of course, everyone wants to live in a more moral, ethical way and achieve our potential and fulfill our destiny, which would lead to God’s favor, right? Everyone would want that. But I do think that this phrase, that she found favor with God, can be tricky. Because it doesn’t mention any of those actions. It doesn’t talk about her personality. And because men have always been in a position of power, women have tended to always want to please men and find favor with men a little too much.

So this feels like it feeds that tendency in women and it sets up that pleasing inclination as a virtue that women should aspire to. And then as the story unfolds, we learn that Mary’s role really is only to submit and to be passive. She acts as a vessel to facilitate the real work of salvation, which will be performed by her son. So the only time we hear from Mary in the New Testament is in the Book of Luke. And as I even say that, it reminds me that we only hear Mary’s voice through a male author. There is no Book of Mary. We never get to hear from Mary herself. And we know that the Book of Luke was actually written between the years 80 to 110 and there is evidence that it was still being revised well into the 2nd century. So that’s like me quoting something that I heard was said in around the year 1900 or even earlier. Or rather, that’s like a man writing down something that a woman reportedly said in 1900. So, I mean, that’s just important to keep in mind, but that’s all we have. So here is what the Bible says that Mary said, Mary’s own words, but again, recorded by Luke in around 110. So Sophie, could you read that?

SA: This is Luke 1:48-49 in the King James Version. “And Mary said, Behold the handmaiden of the Lord, Be it unto me according to thy word. For he hath regarded the lowest state of his handmaiden. For behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things, and holy is his name.”

AA: So here Mary is depicted as an object whose self-worth is derived from the Almighty doing great things to her.

She describes herself in debasing terms, being of low estate, presumably feeling unworthy of the honor. She takes comfort in the way she’s perceived by others. The Lord has regarded her, and all generations will call her blessed. And thus her value is not based on an assessment of her own merit. but on the reassuring reflection of approval that she receives from male authority and from other people.

Another point that occurred to me is that Gerda Lerner points out in the creation of patriarchy that men have always been the symbol makers. And the male authors of Genesis created an Eve whose sin was disobedience to patriarchal authority. So like Sophie pointed out, Mary was seen as having an equal weight to balance out the sin of Eve, like in that Furtmeyr painting. In order to do that, she has to be the perfect woman in the way that Eve was the imperfect woman, which means that if Eve was disobedient, then Mary has to be obedient, and she is. So it’s no wonder that the early church fathers made Mary almost a goddess. She’s a goddess who’s totally obedient to patriarchal authority, totally passive. She’s silent. She’s beautiful, she’s a mother, and she just gets all the positive qualities projected onto her that the men in control of the religion at the time wanted her to have.

And I’ll mention here that if listeners are interested in reading more about this, I highly recommend Mary Rubin’s Mother of God which has tons of information and pictures of art depicting Mary. And also the other book that I read that I would recommend is Marina Warner’s book. It’s called Alone of All Her Sex, The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary. Both are really, really interesting readings of the history of Mariology.

Okay, so that is all we have on the Virgin Mary. Sophie, will you tell us about convents? When did the church start convents for monks and nuns?

SA: Well, nuns and monks were around before convents were. Some women would tell people they were brides of Christ, and in the 300s, when monks started their own monasteries, the women joined them. So there would often be a monastery and a convent next to each other. These convents were a big deal for women because they gave them another option other than marriage, and marriage could be really hard for women back then. Girls grew up with the expectation from the bible that their husbands would rule over them and that they would have children. Lots and lots of children. And the Bible says women will give birth in sorrow, and that they will basically do housework all day, every day, for the rest of their lives. So for many girls and women, becoming a nun was a very appealing option. Also, for a while in Europe, many families put their daughters in convents because they knew it was their only opportunity to receive an education. Galileo did this with his daughter, and you can read their letters back and forth between him and his daughter in the convent.

AA: Right, exactly. I read the book Galileo’s Daughter: a historical memoir of science, faith, and love by Deva Sobel a few years ago. It was their actual letters back and forth is really, really interesting.

SA: Yeah, so convents became centers of learning for women. In the book, Alone of All Her Sex, Marina Warner writes that, “The history of the church is illuminated by saints of genius who were able, once they had capitulated to the conditions the church demanded, to assert their ideas and their authority as independent and active women. Each community had a mother superior, and even though the mother superior was supervised by men, the nuns did get to live in their little cloisters of sisterhood, and they got to have female authority figures. They got to look up to Mary as an idol and a mother figure, they got to study the lives of female saints, they got to commune with other women, and they got to receive guidance and direction from abbesses.” And I should say that it still happens, I’m speaking in the past tense because I’m thinking about the early church. But this is still the life that’s available to Catholic nuns.

AA: Right. Remember in Spain, there were lots of nuns like everywhere. We would see nuns all the time and we were always on the lookout for the convents that sold cookies as, as fundraisers for their convents. Do you remember that? Cause their cookies were really good!

SA: I actually don’t remember that, but that sounds fun. I wish I remembered; I was six.

AA: Anyway. Okay. I have just two thoughts to wrap up this portion on Catholicism. And again, I want to offer these observations gently because I have friends who are Catholic and I have deep respect for many aspects of the church, and I’m also kind of jealous that they have a mother in heaven figure and so many female saints as spiritual role models. But three quick points. First, as we talked about, as powerful as it is to have a divine feminine presence that you actually talk about and you can talk to within a Christian religion, I do think it’s a problem that she is a role model of subservience and passivity and that it perpetuates the hierarchy of men above women.

A second takeaway for me is Marina Warner’s book is called Alone of All Her Sex because she is the only woman who’s able to both be a mother, which is the prized feature of womanhood within this religious tradition and also be a virgin, which is the other prized feature of womanhood. And obviously being both of those things, a mother and a virgin, being both of those things at the same time is impossible, right? And that sets up a lot of religious women with an impossible paradox of having to be pure and not sexual on one hand, the virgin, and then be sexual, on the other hand, in order to please men and to become mothers. And that’s a psychological schism that plagues a lot of women.

SA: I do want to point out that you can still be a mother if you adopt children and you’re still a valid mother.

AA: Oh, you mean like you can be a virgin and a mother at once? Like people who adopt children?

SA: Yeah, I do mean that and that doesn’t take away from how this is still a really hard thing that women have to deal with, but I did just want to point that out.

AA: Well, that’s a really good point. That was a generalization. I suppose this would be like most of the women on it at this point in history, probably maybe heterosexual married women couldn’t be a virgin and a mother at the same time. And those were kind of the, those two expectations of women are impossible. Probably in their lives more, but I appreciate you making that distinction.

SA: Well, yeah, I’m just saying like today that there are other options.

AA: That’s a good point.

Okay. A third point is about convents and the education that women could get inside the abbey was wonderful for those women, but that kind of education and that kind of empowerment wasn’t available to everyday women outside the convent. So just kind of like Mary was kind of an exception among women, she was alone of all her sex who could occupy the positions that she did. Also, the nuns were exceptions. They were kind of alone of all their sex as well because those, those benefits of living in a. in a convent weren’t available to most women at the time.

I read a book called Women and the Shaping of Catholicism by Marianne Zimmer and Zimmer says, “The unfortunate reality is that the positive evaluation of the woman Mary has not functioned to elevate women as a whole from being identified as temptress or as the original Eve. Women in general continued to be identified with sinful Eve, while Mary became the contrast or exception to all other females. This form of idealization continues to permit the veneration of the heavenly Mary while excusing the control and domination of actual contemporary women.” So in other words, since most ordinary women were not virgins, And most ordinary women couldn’t live in convents, those freedoms couldn’t apply to them.

In 1517, a Catholic priest, former monk, and doctor of theology, Martin Luther, wrote his famous 95 Theses, which criticized some practices of the Catholic Church as being out of line with the original teachings of the Bible, but which he almost certainly did not nail to a church door. I wish he did.

SA: I know. It would be so fun and dramatic. What a way to start.

AA: Totally. How do we start something, right? So iconic and there’s so many paintings of it, but apparently that did probably did not happen. But anyway, he did write the 95 Theses though. He did not nail them to a church door. His main focus was based on a personal epiphany that he had while reading the scriptures, that it was faith that saved a person, not their works. He pulled back from all the additions that had made by been made by the Catholic Church and declared that only scripture, or Sola Scriptura was valid doctrine. So there go all the saints, including all the female saints. There goes Maria Regina, the, the Queen Mary with the crown and all of that artwork and the Virges Auvergne statues, right?

SA: Yeah, many Protestants reacted so strongly against the Catholic icons that they stormed into Catholic churches all over Europe and destroyed all the art that depicted Mary and the saints. Remember those churches in England that still had the statues missing or paintings that had their faces scratched out due to the Protestant Reformation?

AA: Yeah. Exactly. I do remember that. It’s so sad to see those beautiful images of women, especially because they were all images of women, right? In the churches with their faces hacked off very crudely and false statues missing.

SA: Also, as an artist, it just makes me sad because I’m like, someone put so much work into making that beautiful art. It doesn’t mean you get to just destroy it.

AA: Yes, exactly. And there goes the option of women going into monasteries. Once a place had been kind of overtaken by the Reformation, they would just close down monasteries. And so women didn’t have that option anymore. This changed many aspects of daily life for women. There’s a pamphlet from Germany in 1524—and remember this was right after the invention of the printing press also, which made it possible to spread Protestant reading materials all over Europe. That’s how it spread so quickly—and this pamphlet said, “Even the most beloved Mother Mary makes herself humble and small, for it is God’s will that honor be given only to God.”

This must have been a really, really difficult transition for first generation women converts to Protestantism, who are raised to pray to a queen of heaven and to pray to female saints who looked like them and understood what it was like to be a woman. When Catholic women gave birth, for example, they could pray to the patron saint of childbirth, Saint Margaret. But then once they converted to Protestantism, they didn’t have that womanly spiritual support anymore. In fact, there’s a quote from the Protestant John Calvin that says that women in childbirth, “groaned and sighed to the Lord, and he received those groans as a sign of their obedience.”

SA: Ugh, it’s just awful. It’s devastating to think about the fact that the action of one man was able to take away something so sacred from women, even if it didn’t impact everyday life, which it did. I’m sure having female saints to pray to made the women in difficult circumstances feel less alone. Who can they rely on now? And this is also taking the options of education for women away because of the loss of convents, it really shows how powerless these women were, their powerful symbols of womanhood could be taken away by a man so quickly.

AA: Right. Because every single governing structure was a hundred percent men, right? So they were always dependent, but here is where a man in power did something that would actually eventually put power into the hands of women themselves. With Luther’s emphasis on sola scriptura, he set in motion the very thing that would eventually allow everyday women to become educated and think for themselves.

Prior to the Protestant Reformation, most people were illiterate. The only people who received an education were royalty or lawyers, or like we already talked about monks and nuns and monasteries. But Luther wanted every Christian reading the Bible in their own language. including women. And that meant that for the first time, women started learning to read. They started acquiring the vocabulary and critical thinking skills that accompany literacy. And they started forming a personal relationship with God that was less mediated by authority figures. And that led them to having their own opinions and asking their own questions. That’s always what education does for people, right?

This brought about a lot of pushback from ministers, but the wheels were already set in motion for women and there was no turning back. So Luther kind of accidentally empowered women to eventually challenge patriarchal systems. In fact, I had the thought that it’s kind of like how Luther’s Catholic teachers, when he was training to be a monk and then a doctor of theology, didn’t know that they were giving him the tools that he would eventually use to critique the Catholic church. And Protestantism did that same thing for women. And there we have it. So, Sophie, what is one of your takeaways from today’s discussion?

powerful symbols of womanhood could be taken away by a man so quickly

SA: Just the fact that though Mary was venerated and respected, it was all because of her ties to powerful men. Her power as a mother was not about her birth-giving feminine power, but about kind of her giving birth to Jesus and how her virtue was not extended to women as a whole. Like we talk about women as a person and then women as a class and if we’re like interpreting women as a class, Mary’s stature was not elevating women as a group. Just because one disadvantaged person was able to be super successful does not mean that people in that same position are suddenly equal.

With all that said, I think that Mary can still be a powerful symbol for women. How meaningful it must have been to be able to pray to a woman who shares your experience. So my takeaway is kind of, even if her holiness was not enough to help women’s position in society, that doesn’t mean that her existence couldn’t be a very positive thing for Christian women, and I’m grateful for the way she impacted Christianity.

AA: What’s one takeaway for you? Yeah, I have two main takeaways. The first one is about power structures. I remember doing a research paper on the Jewish community in Rome in the Middle Ages. The Jewish community was sometimes quite free and they really flourished, but sometimes their synagogues were burned and they were put in a ghetto and forced to quit their jobs and to wear distinctive, distinguishing clothing, and were really, really oppressed and restricted in their lives. And it just entirely depended on who the pope was at the moment. So there might have been, and actually there were, generations of Jewish people who thought like, Oh, yay, the hard times are over. Everything’s better now because they got a pope who was more sympathetic to the Jewish community. But that sense of wellbeing was deceiving because even if it lasted a couple of generations, which again, it sometimes did, it could go back to being restrictive at any time. And it did. It would go back and forth, just depending on the pope. They were totally dependent on the whims of a power structure from which they were excluded. And I thought of that as we were talking today about male church leaders telling women whom to identify themselves with, whether it was Eve or Mary and how to be as women and what their status was and that determined what they could and couldn’t do and really how they even saw themselves. And sometimes things were okay for women. In fact, one thing that we didn’t even talk about today is the evidence that there is that women officiated in some priesthood functions in the early church. And one book I recommend on that topic, if you’re interested, is it’s called When Women Were Priests. It’s women’s leadership in the early church and the scandal of their subordination in the rise of Christianity, and that book is by Karen Jo Torjeson, and that will be listed on the website as well.

But that phenomenon within the early Catholic Church reminds me of the Mormon church too, where women used to be able to give priesthood blessings and officiate in other ordinances that today are restricted for women. And the women’s organizations, like the Relief Society, used to have a lot more autonomy and financial control, but then those things were taken away. And that’s why we’re talking about these topics on Breaking Down Patriarchy, because these religious power structures excluded and continue to exclude most men and all women, and that just leaves women at the mercy of a governing body that is 100% men.

And then my second point is if we don’t really know what Mary really said or who she really was, because we only see an image of her that has always been mediated by men, then that gives us a lot of freedom. Remember that part in The Secret Life of Bees, which is a book by Sue Monk Kidd, which I love. Remember that part with the Black Madonna? Those African American women had their own religious observances based on a statue of a Black Madonna with this very special mystical meaning, and they had religious ceremonies and that they did together, but then at the end of the book, you discover that one of the women just made it up, right? Sue Monk Kidd promotes that in several of her books. She writes examples of coming up with spiritual practices that feel authentic and meaningful to each individual person.

And so I guess just going along with what you said and what I said in my last point, a man shouldn’t be able to tell a woman that she’s not allowed to pray to a Black Madonna, for example. A man shouldn’t be able to tell a woman that she’s not allowed to pray to the matron saint of childbirth when she’s in labor, and a man should not be able to tell a woman that she can’t talk to her own mother in heaven. So I just feel that if communicating with the Virgin Mary feels empowering and augments and enriches a woman’s sense of spirituality, then I would just say, I would encourage people to be authentic and maybe meditate and think about a spiritual practice that makes you feel whole and feel happy and brings light to your life and give yourself the permission to worship or to meditate in any way that feels right for you, so. I guess those were my two takeaways.

So that’s it. Sophie, thank you so much for participating in this episode. That was, you did such a fantastic job.

SA: Thank you for having me.

Having female saints to pray to made the women in difficult circumstances feel less alone

Who can they rely on now?