“I am inhabiting my body and being who I am and working very hard at becoming unapologetic about who I am.”

As new generations increasingly have the knowledge and social acceptance to explore their identities, the number of openly transgender people in our world—especially transgender youth—is rapidly rising. Yet despite these recent spikes— the transgender community is still comparatively small: making up roughly 0.6% of the global population. As a result, many cisgender people (meaning those of us whose gender aligns with the one we were assigned at birth) have little to no lived experience interacting with transgender people. What we’re exposed to instead is whatever our media, political, and social leaders choose to tell us about them, resulting in a perilous gap between actual transgender people and a series of cultural stereotypes. This gulf in our understanding not only endangers the trans population, it harms all of us, discouraging marginalized demographics from working together, making it even more difficult for us to dismantle oppressive structures, and denying cisgender people the chance to love their trans neighbors.

Fortunately, some transgender people are stepping forward to help bridge this divide, sharing their personal stories, dispelling dangerous myths, and helping us envision a more egalitarian future for all. On today’s episode I’m happy to say we’ll be joined by two such voices: Sam Rose Preminger and Domi Shoemaker

Sam Rose Preminger shares their story of discovering, resisting, and ultimately learning to love their transgender identity.

Domi Shoemaker is interviewed about their relationship to gender, colonialism, patriarchy, and the power of storytelling.

Our Guests

Sam Rose Preminger

Sam Rose Preminger (they/them) is a trans-nonbinary, Jewish writer and publisher. They hold an MFA from Pacific University, serve as the Editor-in-Chief of NAILED Magazine, and are a contributing editor at Lightship Press and Write Bloody Publishing. Their poetry has appeared in numerous publications online and in print. Their debut collection of poems —’Cosmological Horizons’ — is forthcoming from Kelsay Books (Summer 2022). They live in Portland, OR, where they’ve acquired too many house plants.

Domi Shoemaker

Domi J Shoemaker (they/them) is an Idaho-born genderflexer who founded the quarterly reading series, Burnt Tongue, after cutting teeth in Tom Spanbauer’s Dangerous Writers workshop. While finishing an MFA in Writing in 2015, author Lidia Yuknavitch asked Domi to help her create the Corporeal Writing Seasonal Workshop Series. With a resounding yes, Domi is now the Corporeal Writing Seasonal Workshop Co-Facilitator. Domi has published at [PANK], Nailed Magazine, Unshod Quills, Gobshite Quarterly, and has a story in the anthology, The Night and The Rain and The River, from Forest Avenue Press. They were recently featured in the literary radio theatre podcast, Storytellers Telling Stories.

PART ONE.

Sam Rose Preminger

In my childhood, I felt most at home when I was by the edge of a pond, holding a net in my hands to scoop up frogs, or a stick to overturn mossy logs and admire the mealy little microcosms underneath. The natural world, it seemed, was brimming with diversity, thriving on the interplay of unique creatures, each as marvelous as the next. And I recognized myself as an equal spirit within that intricate community of life. I knew I belonged, and still to this day when I imagine myself most being myself what I see is my early childhood: a slender, spectacled kid taking shelter under the leaves of sugar maples and silver pine, dappled by the summer rains of central New York.

But reality is that trips to the woods were an exception in my childhood. Vastly more numerous were trips to the shopping malls of suburbia, traffic-locked drives down dismal Long Island highways and long strolls past the homogeny of plastic paneled, ranch style houses that metastasized across my hometown sometime in the early 50’s. In case you haven’t caught on, I didn’t like where I grew up. Now, I will say that most of my family still lives in that area and sometimes I can see its charm — beachside cafes and a good school system and such — but suffice it to say that, for a queer kid trying to understand themself, the normativity of Long Island’s culture could be suffocating.

See, from a pretty young age I started to stand out. I simply was not turning out to be the person that people expected me to be. And in this context, it’s important to know that I was Assigned Male At Birth (AMAB). All that means is that a doctor looked at my external anatomy and made a binary choice, and my parents agreed. For many years that was that. I was a boy, a male, and would grow to be a man. Or at least that was supposed to be that, but even in grade school I was off script for what the world around me seemed to say a boy should be. I didn’t care about sports or cars or action films. I wouldn’t eat meat because the idea of animals being killed, chickens being turned into chicken nuggets, made me cry. I just…wasn’t matching the masculine mold that had been laid out for me. I was sensitive, soft, and let’s be real, about as socially graceful as a giraffe on stilts.

As a result, from an early age I started to hear words like ‘weirdo’ and ‘loser’ loosely floated my direction. At best, I was praised for being unique, for marching to the beat of my own drum! At the worst moments, I was told that there was something wrong with me. That I was a freak. And then, as I got older, ‘faggot’ became the common slur for me. The environment I grew up in, the culture of patriarchy and homophobia I moved through, made it clear, in no uncertain terms at all, that I did not belong. And I agreed; they were right. I didn’t belong.

There’s a quote from the poet and playwright TS Eliot that I remember reading sometime in my youth where he writes: “I must tell you that I should really like to think there’s something wrong with me — Because, if there isn’t, then there’s something wrong with the world itself — and that’s much more frightening!”

By the time I reached high school I had thoroughly internalized that mindset. There was something wrong with me. Something off. The sense of belonging I’d felt by the pond as a child was severed, and I knew that the man-made world, the ‘real world’, had no place for…whatever I was. In those years I was riddled with depression and anxiety, oftentimes unable to go out in public, missing school for weeks at a time, terrified of being seen. I didn’t want anyone to look at my failure, how I was failing to become a man like I was told I should be, like I needed to be.

Had I had the language for my identity that I have today, things might have been different. Had I had queer and trans role models, or seen people like me as anything but a villain, a victim, or punchline in the media, then maybe things would have been different. As my teenage years and high school played out, however, I’d end up trying to end my life twice before starting college. When it was finally time for me to leave home, I took my finger and traced a line across a map of the United States, deciding that that was where I would go; as far away as I possibly could. Someplace no one would know me. Someplace I could disappear. I moved from Long Island, New York to Portland, Oregon at 17 years old with no intention of ever going back, wanting to be forgotten.

I’m going to let you know now so aren’t worried: moving to Portland would turn out to be a fantastic decision for me. My life was going to get better. But before that could happen, I was going to need to reckon with my identity. I’d have to come out to myself and others and that was not going to be an easy process. Rather, I resisted it for years, trying to be anything but transgender. In my late teens I came out as bisexual. In my early twenties I came out as queer, but I knew I hadn’t put my finger on it yet. It was like I was trying to put band-aids on a wound that needed stitches. I had internalized so much transphobia, that the possibility of me being transgender was completely intolerable, something to be bottled up at all costs.

So before moving further, I want to take a moment to discuss where some of that internalized transphobia was coming from. And the answer is actually pretty simple: it came from entertainment. Growing up in a heteronormative community, I’d never had the opportunity to meet an openly transgender person and so my understanding of what trans lives looked like came almost entirely from the movies and TV I watched. And what that media showed me did not look good.

For example, the very first representation that I saw of an AMAB (meaning Assigned Male At Birth) person wearing feminine clothing was in the Robin Williams’ classic Mrs. Doubtfire. In the movie, Williams plays a divorced father who attempts to sneak back into the lives of his children and former wife by dressing up as a woman and pretending to be their nanny. Hilarity ensues. Audiences laugh as Williams struggles to fit into a dress. We laugh when he jokes that he looks like a serial killer. Several gags revolve around Williams revealing his deep, masculine voice while dressed in women’s wear. And finally, the film reaches its climax when the cross-dresser is outed, being called a ‘he-she’ after having been caught using a bathroom. It’s funny…right?

The environment I grew up in, the culture of patriarchy and homophobia I moved through, made it clear, in no uncertain terms at all, that I did not belong.

I want to be clear, I loved this movie as a child and I think there’s still a case to be made for its campy treatment of gender-bending being at least somewhat progressive for the 90’s. But the fact of the matter is that, for a young transgender child, this beloved family movie taught me that cross-dressers and other gender-nonconforming people are tricksters, they’re trying to lie to us and get away with something, and the very idea of me, an AMAB person, growing up and wearing a dress was not only laughable, it was blockbuster comedy.

Let’s fast forward a few years. In another instance, I’m invited to a childhood sleepover where my friends and I watch another comedy classic you might know, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. This time the movie kept its transgender character — who’s stolen a police officer’s identity in order to kidnap and kill people — a secret until the big finale, when the film’s hero comedically tears this transwoman’s clothes off, exposing her genitals, and then proceeds to violently retch, struggling to hold back vomit at his discovery. Again, this was not a one-line joke in a minor studio release. This was the climactic plot point of a film that held top spot at the box office for weeks. And, as a child at that sleepover, I watched this trans character treated with utter disgust and contempt while laughing along with my friends. Transgender people were untrustworthy and their bodies repulsive. Again, it was funny.

I could go on and on with more examples of transphobic media from my youth. Seriously. It was omnipresent. Friends, Silence of the Lambs, Ally McBeal, Sex & The City, South Park, Dude Where’s My Car?, The 40-Year-Old Virgin. The list goes on and on and on. Any time a transgender person was shown or referenced on a screen, they were a punchline or a monster — oftentimes both. And I watched it all, deeply internalizing these hateful stereotypes.

And here I want to pause and offer a quick note about the importance of representing queer characters in media, especially in children’s media. I want to make this as clear as possible: the push for representation is not about encouraging kids to be gay or trans — after all, I grew up constantly watching heterosexual cisgender characters kiss and date…and it didn’t make me straight. This isn’t about changing people. Representation is about making sure all people, especially kids, can see characters who look and act like them on a screen. It’s about making sure queer or questioning children can envision futures themselves. It’s about making sure they know, like every other child, that they can find love in this world and are worthy of loving themselves.

I wish I could say things have gotten much better since the 90’s and early 00’s, but the reality is that our media representation of transgender people is still incredibly lacking. We’re seldom seen and, when we are represented, it’s often with dangerous inaccuracy.

In a survey of 102 television episodes featuring transgender characters, GLAAD (the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) found that 54% of the episodes contained negative representations of trans people, while another 35% were marked as problematic. Only 12% of these episodes were found to represent transgender characters in a fair and accurate manner. That’s about 12 episodes out of 102.

Beyond this, the GLAAD survey also found that transgender characters were cast in a “victim” role at least 40% of the time, and cast as killers or villains at least 21% of the time. That means 61% of the time trans characters appeared on the screen we were shown as the victims or villains of these storylines and, unsurprisingly, the survey also found that 61% of the cataloged episodes included transphobic slurs and dialogue.

Some of the negative representatives included:

CSI (CBS), which not only featured a transgender serial killer who murdered his own mother, but scenes in which transgender murder victims were openly mocked by the show’s lead characters while examining their bodies and crime scenes.

The Cleveland Show (Fox), in which a man vomits onscreen for a lengthy period of time after discovering he had slept with a transgender character. The episode also contained anti-trans language and defamatory characterizations.

Nip/Tuck (FX), which featured a storyline about a transgender woman who regretted her transition, a transgender sex worker being beaten, and an entire season about a trans woman depicted as a baby-stealing sexual predator who sleeps with her own son.

What this survey tells us is that transgender people are still actively misrepresented in media. Our lives are co-opted and sensationalized in order to sell stories and earn higher ratings, but those ratings come at a real cost for real people. When stereotypes run rampant, when trans people are reduced to victims, villains, and jokes these ideas become reinforced in viewers, and these viewers often have little other knowledge of what it means to be transgender. Worse still, these ideas become reinforced in the minds of trans youth, warping their self-perception and undercutting their self-esteem (just like they did for me). Finally, these stereotypes can be, and have been, wielded by politicians to further persecute and restrict the freedoms of the transgender citizens they’re meant to represent.

I’ll talk more about transphobia in our politics later, but for now suffice it to say that – when we consider the aggressive heteronormativity of our culture, the active misrepresentation of transgender and other queer people in media, and the near constant barrage of hatred from elected officials – I really think it’s something miraculous when any person manages to come out of the closet at all. It is so frighteningly easy for me to imagine a world in which I never made it that far.

We’re seldom seen and, when we are represented, it’s often with dangerous inaccuracy.

By the time I was in my early twenties I believed — I knew — that there could be nothing worse than being transgender. The culture I’d been steeped in, been breathing like oxygen, had completely convinced me that a trans person’s life was a waking nightmare. They were destined to be reviled, abused, outcast, or worse. I knew a trans person’s life would only be one of two things: a comedy, because nothing is more worthy of derision and mockery than someone ‘pretending’ to be a different sex, or a tragedy, because nothing is more revolting and untrustworthy, more deserving of violence, than a trans person’s body. I didn’t want that to be me. That couldn’t be me. I was terrified. I was so consumed with self-loathing; I couldn’t even fathom the possibility that I would love myself one day. Instead, in my early twenties, I was disgusted by the thoughts that would sometimes well up in me. For the truths I was constantly trying to tell myself.

It didn’t even make sense. I knew I wasn’t a woman, but more and more I was realizing that I wasn’t a man. What did that make me? I didn’t know the word non-binary back then. The words that patriarchy had taught me were ‘freak’, ‘tranny’, and worse. I shoved those thoughts, that possibility, those words, as deep down as I could. I tried to hide from myself with statements like “I’ve just got to play the hand I’ve been dealt” and “gender’s really not a big deal to me.” I did everything I could to run away from the dawning discovery. I tried to drown the truth in alcohol. At this point in my life, drinking and fantasies of suicide had become a near constant companion. In the mornings I would wake up hungover, my memory hazy, and find letters I’d drunkenly written to myself from the night before — begging myself to confront who I really am. To do anything at all. I’ll quote from one of those letters now:

Sam — this has to stop.

It didn’t always hurt this much. I know it hurts now. You need to be who you are.

Remember the pond. The frogs and deep forest moss.

Remember music. Remember the sounds of the summer rain.

I promise you, you don’t want to die.

Try to remember the rain.

Okay. So, I’ve talked a lot already about the ways our culture propagates distrust, hatred, and disgust as appropriate responses to transgender people. That was a large part of my struggle. But another part of my struggle was about knowledge, about history. At this point in my life, I knew I wasn’t a man or a woman, but I didn’t know there were other possibilities. I was defining myself by what I wasn’t, and had no clear grasp on who I was. What else was I supposed to do when I’d never heard what the word ‘non-binary’ even meant? That information had been kept from me, and it occurs to me that a few folks listening might have not been exposed to this knowledge either, so I’m going to share, real quick, some history of non-binary, or enby, people.

Let’s get a definition going first. Quoting from the National Center for Transgender Equality: “…most people – including most transgender people — are either men or women. But some people don’t neatly fit into these categories. For example, some people have a gender that blends elements of being a man or a woman, while other people have a gender that is different than either male or female. Some people don’t identify with any gender. Some people’s gender changes over time.

People whose gender is not male or female use many different terms to describe themselves, with non-binary being one of the most common. Other terms include genderqueer, agender, bigender, and more. None of these terms mean exactly the same thing — but all speak to an experience of gender that is not simply male or female.”

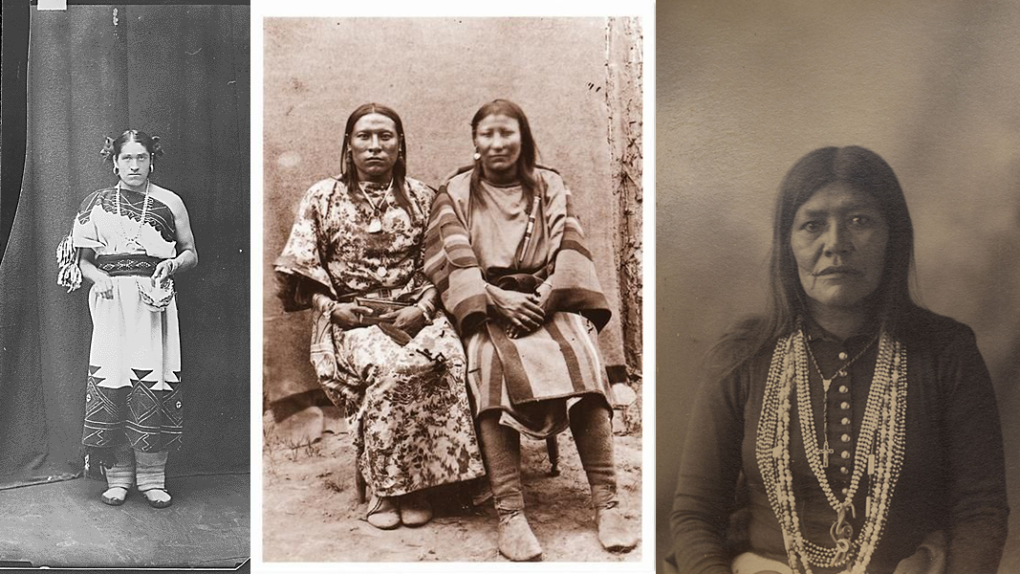

Non-binary identities are numerous, and non-binary experiences are each as varied and unique as the experiences of any other gender. There is so much space beyond the gender binary. Now that we know who we’re talking about though, the other important thing to know (and that I didn’t know until recently) is that non-binary people have always existed. We’ve been here as far back as gender’s invention and historical records of non-binary people can be found across the world.

To quote transgender archeologist Gabby Onomi Hartemann “I often find myself overwhelmed with deep feelings of nostalgia when I learn about ancient times. Human beings have lived with fluid notions of masculinity and femininity in various cultures throughout most of human history without their existences being demonized and violated.” Examples of these nonbinary identities, which have existed throughout history and into the present day, include the Hijra in India, Muxes in Mexico, Māhū in Polynesia, and numerous Two-Spirit identities across North America.

Now, you might be wondering: if non-binary and third gender identities have existed for so long and in so many places, why the heck hadn’t I heard of them before? It’s a great question that’s deserving of an answer.

Some of our lack of awareness can be chalked up to cisgender bias in academia. For instance, according to Doctor Pamela Geller, a scholar of bioarcheology who specializes in the analysis of ancient human remains, “despite the fact that archaeologists regularly come upon evidence that some people did not fit sex and gender binaries, those researchers still have a tendency to diminish their relevance, relegating them to “anomalies” or “ambiguous cases.”” And then, of course, there’s also a reason we’re made to feel as if it were new. As if we were inventing it. As if it were all made up. And that reason, were I to sum it up in one word, is this: patriarchy.

You may be thinking, hold on — isn’t patriarchy about the oppression of women? Why would patriarchal structures care about trans people? Well, let’s look at that for a moment.

Patriarchy, at its very core, is built atop the belief in a gender binary. In fact, I would argue that the survival of patriarchy depends upon gender essentialism and binary gender to do the following:

-Determine and enforce a division of labor (often one where the brunt of undervalued and exhausting work falls on the shoulders of women).

-Regulate the behaviors, appearance, and value allotted to each gender.

-Claim that these social categories are natural and inviolable.

To put it another way, patriarchy relies on the rigid division of all people into two categories in order to situate one category — men — above the other — women. This means that the very existence of transgender and other gender-nonconforming people would challenge that power structure…and we are punished for it.

Our political leaders, faith leaders, and others paint us as predators and enemies to women, encouraging oppressed populations to fight amongst ourselves.

Our nation’s laws target trans people, especially trans youth, with draconian restrictions on their rights to access things like lifesaving healthcare, safe spaces, or even their access to the bathroom.

Our media represents trans people as deceptive deviants, villains, victims, or as the punchlines to hateful jokes.

In short, the systems of patriarchy have historically, and are in this very moment working to silence, and if possible, erase the existence of transgender people.

Throughout our history the gender binary has been treated as immutable, codified in law, enshrined in religion, and aggressively enforced by a male-dominated culture. And yes, most often this binary is wielded as a bludgeon against women, restricting their freedoms and social roles in favor of men’s dominance, but the transgender population is enduring constant collateral damage from these patriarchal norms. I will say that again: regardless of your personal beliefs on gender, the fact is that the gender binary has historically been and is still today used as a tool for enforcing patriarchal norms. It is used as a weapon against women, and its impact greatly injures trans people as well.

With this in mind, it’s no wonder that transgressions against this binary system have been erased from our cultural memory. Knowledge of transgender people has been carefully concealed and eradicated by patriarchy for centuries. It’s the reason that the Nazis burned over 20,000 books on sexuality and gender during WWII, it’s the reason that British colonizers attempted to eradicate the gender-nonconforming Hijra population in occupied India, and it’s the reason that the Trump administration erased all mentions of trans people from the White House’s website and attempted to re-define the word ‘gender’ to specify a person’s assigned sex. Trans erasure (just like the erasures of women and people of color), is not accidental – it is a tactic used to protect patriarchal institutions. By creating a cultural narrative that transgender people have no past, the patriarchy makes their argument that we should have no present become more palatable. They convince trans people that we should be grateful for being permitted to exist in ‘their world’ at all. And convince all of us that the gender binary is absolute, unchangeable, and neatly and naturally divides society into powerful men and the women they preside over.

Fortunately, however, as increasing numbers of people come forward to challenge this binary, to share their stories and try to correct some of the damage our media and other institutions have wrought, that patriarchal narrative of two stringent genders is beginning to crumble. We have a long, long way to go. There is so much work ahead of us. But it’s possible to see some light at the end of the tunnel now, to imagine futures where these cruel systems are little more than embarrassing relics of the past. And I’m happy to say that — with the support of friends, family, and partners — things did get better, at least for me.

In my mid-20’s I came out of the closet and into my identity as a transgender person, and anyone whose known me will tell you that I’m happier today than I’ve ever been before. Since coming out, life has only gotten better. I’m finding peace within myself. Acceptance of myself. I’ve been finally falling in love with myself. So many of the internal struggles I spent my younger years wrestling with have washed away, and I’m happy to be in the process of healing the injuries that went deeper. And yet, now living as an openly non-binary person, while many internal struggles have resolved I’m suddenly faced with all manner of external challenges. However high I hold my head up and eagerly I try to engage with our world, it is often not a kind place for transgender people.

It takes practice and thought and care for trans people to move through this world that patriarchy has created. To quote non-binary activist and author, Alok Vaid-Menon, “the days I feel most beautiful are the days that I am most afraid.” As transgender people, we have to consider what streets we can walk down. What clothes it’s safe to wear. What bathroom we won’t be a target in. And if we make a misstep, there can very very real consequences. Sometimes those consequences occur regardless.

Every transgender person I know has been threatened with violence, and most have experienced it. Even in my progressive city, multiple transgender women of color have been murdered without consequence. Walking down the street it is almost a guarantee that I will attract stares, if not harassment, from people I pass by. There is still the issue of trans misrepresentation anytime I turn on my TV, and if I dare look at politics, I’m buffeted by a veritable banquet of hate.

To put it simply, there are far too many anti-queer and anti-transgender bills either active or under consideration across the country. 238 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills were filed in less than three months in this year, 2022. This is the highest incidence of anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation being introduced in American history to date, though the number climbs year by year. The majority of these bills target trans people explicitly. Over 23 were aimed at trans children. There will be an updated list of active and recently defeated anti-queer legislation included in the show notes, but highlight include:

A recently proposed bill in Ohio which, if it becomes law, will force girls and young women to submit to invasive gender-verification tests if they want to stay on their high school and college sports teams. And beyond this, in the last six months alone, Idaho, Arizona, and Louisiana have all considered bills forbidding doctors from providing gender-affirming (and I’ll add, often life-saving) care to transgender youth…though notably all of these bills make exceptions to allow involuntary surgery on intersex babies so that they can be sorted into the binary as well.

While many of these bills won’t become laws, a few of them will, and the very fact that we so actively debate transgender rights in the halls of our government carries a serious toll. Mental health experts draw a direct line between statements made by politicians and individual wellbeing. According to Dr Adam Jowett, the chair of the British Psychological Society’s Sexualities Section, “There is strong evidence that minorities experience greater levels of stress when their rights are being debated.” And I can attest to the effects of this stress myself. As many other marginalized people know, it is exhausting to watch, after countless centuries of our ancestors’ struggling for liberation, as small homogenous panels of people who look nothing like us debate whether or not we should be allowed to have rights.

Before wrapping up, there’s one last story I’d like to share. I’m going to share a story from just a few months ago. So this was back in Autumn of last year — infection rates in our area were low, so my partner and I decided to go out to our first concert together since COVID had begun. We both love dancing and live music and were beyond excited to be seeing one of our favorite bands. I even had a new outfit picked out just for the occasion: an orange turtleneck, my grandmother’s faux gold necklace, and a poofy black skirt that was going to be perfect for spinning around in. We got to the venue early, grabbed some drinks from the bar, and had just started scooching our way towards the stage when it hit me: a sudden small dread. I had to pee.

Now, some listeners might be wondering: what’s the big deal? You had to pee…go use the bathroom.

Well, here’s the big deal. A 2013 survey from UCLA’s Williams Institute found that nearly 70% of trans people had experienced negative interactions in public facilities — from dirty looks to snide comments to physical violence. Honestly, based on my own experience, I’m surprised that percentage isn’t higher. Harassment and assault in public bathrooms are a constant risk for trans people. This is the reason that transgender people like myself run into problems with dehydration and urinary tract issues. We are literally afraid to use the bathroom…although from the popular cultural narrative around trans people and bathrooms, you might think otherwise. To summarize simply, all of those hateful stereotypes we discussed earlier — remember the one’s where transgender people are presented as liars and villains — that all gets blended with politics here in some truly malicious and misogynistic ways.

The popular story is this: men are dressing up as women in order to gain access to women’s restrooms and assault them. This is rhetoric we’ve heard from political leaders as recently as this March, when North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory signed a law which effectively made it illegal for trans people to use the bathroom, with conservative critics arguing that to do anything otherwise would give “sexual predators” a free pass to prey on women and children. Despite this, however, as of the date of me recording this essay there’s never been a single reported case of a trans person assaulting someone else in a public facility.

I want to emphasize that. There’s never been a single verifiable instance of a trans person attacking someone else in a public restroom. To be honest, I did not know this before doing the research for this podcast. I’m embarrassed to admit I had heard the myth of transgender predators so many times that I thought it must, to some extent, be true. But it isn’t true. In fact, it’s almost an identical twin to fallacious arguments that were once used to advocate for things like racial segregation: it’s the same old claim that (white) men need to defend ‘their’ women from dangerous outsiders. It’s an argument grounded on fearmongering, prejudice, and the treatment of women as a helpless social resource needing to be governed for their own protection. And, alarmingly, it’s an argument that still holds a great deal of power, making bathroom trips a constant nuisance for many transgender people.

I’ll break it down for you. Ordinarily using a public bathroom looks something like this for me:

Step 1) Wait outside until I don’t see anybody go in or out for a few minutes.

Step 2) Hurriedly step in, head down to avoid anyone seeing my face, and rush to a stall.

Step 3) If anyone else is in the restroom already or enters, wait in the stall for them to leave.

Step 4) When I’m certain the room is empty, scurry to the sink, scrub my hands as quickly as I possibly can (and carry disinfectant just in case I don’t have time).

After several years of being openly transgender, I have this routine down to an art. But on that Autumn night I wasn’t at a quiet café or public park: I was in a busy concert venue and both restrooms were crowded with people. Either way I chose, I’d have to be seen. There’d be no hiding. I didn’t want to make the binary decision, but my body was giving me no choice.

Back in the moment, I queue up for the women’s room, my thinking being that 1) it’s the longer line and thus the more respectful one to wait in, and 2) my outfit looks a lot more like outfits in this line than the other. As soon as I stepped into place among the women, I started questioning myself though. A lady in gold eyeshadow in front of me shuffles forward, and I try to convince myself she’s just social distancing, she’s being safe, it’s not about me. If anything, she’s being considerate, but…too late, the anxiety inside me has already started to bloom. Are people looking at me? Is it in my head? Maybe they just like my necklace? My hat? Another woman queues up behind me, eyeing me up and down coldly before clearing her throat. Confusion? Disdain? A man walks past, pausing to glance at me in the women’s line. He chuckles. The woman behind me clears her throat again, louder, but when I look to her she won’t meet my eyes. Had I chosen wrong? Was I just making the line even longer for her? For the real women? This was clearly another place I did not belong.

…the gender binary has historically been and is still today used as a tool for enforcing patriarchal norms.

I slipped out of that line with my head kept down, hurrying over to a quiet corner to lower my mask for a moment and steady my breathing. I assure myself everything’s okay…but the show is starting soon. Okay, I say to myself, we’re doing this. Men’s room it is.

I re-adjust my mask and fix a fold in my skirt. Here we go. Walking through the threshold, I’m buffeted by a buffet of terrifying facts and distressing memories that rush to mind. Detailed accounts of assault. Videos of trans people beaten and dragged out of bathrooms. Portland’s a progressive city, I remind myself. I know I probably won’t be killed in a public space, but hate speech, despising stares, or even a light beating are still all on the menu as far as my amygdala’s concerned. I try to hurry for a stall, but there’s a line of men waiting. I take a spot alongside them, occupying as little space as I can and staring at my shoes like they’re the most awe-inspiring sight on earth. It doesn’t matter. Within a moment a man turns to me and spells it out plain as day: “You don’t belong here,” he says to me.

And I agree.

I had tried so hard to find a solution to this bathroom issue like it were some sort of binary puzzle. I just wanted to be safe and respectful of the people around me, and for heaven’s sake I just wanted pee, but couldn’t do that without drawing this stranger’s ire. I was in the wrong room because there was no right room. This was yet another system that had no place for me. But here’s some good news: we can change this system and others like it.

When I was a child, still catching frogs by the side of that pond, I believed I was a part of the world. As natural, essential, and valuable as a leaf on a tree or a fish in the stream. In the course of my life the forces of patriarchy did their absolute best to strip that belief away from me. To tell me I was abnormal, unnatural, unwanted and without worth. I am still bombarded by these messages nearly any time I step outside or look at my phone. But at least for today I can let those hateful slings ricochet off my self-love. Today I understand that patriarchy is a social construct, not the all-encompassing reality it pretends to be. Who cares if its oppressive systems have no place for me? Today I know I am as much a part of this world as the flowers and the sun, as all of you listening and any other human to walk the earth, and all of us deserve a world where we can blossom and shine. I believe we can build that world together, but it starts with breaking down our barriers, our binaries, and our mistakes.

Learn more about Sam at their website.

PART TWO.

An Interview with

Domi Shoemaker

Domi Shoemaker: I’m looking very much forward to this conversation.

Sam Rose Preminger: Same! Full disclosure for our listeners: the two of us spoke a little bit before this recording session to see what Domi might want to share with everyone, and it became apparent that there was one topic that was circling in their mind: which was colonialism, or de-colonialism to be more specific. But before we get too far into the nitty gritty of it, would you be able to explain for our listeners just briefly what colonialism is and maybe talk a bit about how it intersects with patriarchy?

DS: Yeah. Well, you know, colonialism in a broad sense is basically one group of something going into another group of something and taking it over as if it were theirs. Not always destroying customs, habits, lifestyles, ways of being, but very much usually about that. The way that I have, on a micro level, broken this question down for myself is sort of about the cross-section of patriarchy and colonialism, as in a way that I understand how my brain thinks and how to try to get around, beyond, or through that.

The reason that came up for me is because I was actually speaking with my therapist in this session, and I talked about all these things that I was, negative things I was saying about myself in my head. It’s been a lifelong thing of either not being good enough or smart enough or enough of this or enough of that. It’s still so relevant in my everyday experience. How I’ve been thinking about it is that the way I’ve grown….I was born in 1964, so I’ve been through a lot of years, and I grew up in a small town in Idaho so that was also very relevant to this whole conversation in that the patriarchy has colonized my mind, and I’m not the only one. But I want to speak for myself because, I mean, you can’t live in this world without the patriarchy in some way colonizing your mind, right? I can’t say in the whole world, but in Portland, in the United States, in Western civilization, the patriarchy is all of who we are.

I know that there are a number of cultures who are matrilineal, but not huge points of civilization since way back. And that’s always been refuted as well. My point is it’s really hard to live in the world with all of these expectations about how to be. Bottom line.

SP: Thank you for sharing that. If you don’t mind, I’m actually going to backtrack us just a little bit to go back to you were mentioning your childhood. And I want to get into that because you’ve mentioned that it informed a bit of how you view yourself and function within patriarchy and colonialism today (and also because we spoke already, and I know there’s some cool stuff back there). You mentioned you were born and grew up in Idaho, right?

DS: Yes, I did.

SP: Would you be willing to tell us just a little bit about what that was like?

DS: Yeah. I grew up in a small town in Northern Idaho. I was born in 1964. I grew up with all of the energy and noise around the Vietnam War and still coming off of the end of the 1950s with all of the sort of idealistic mom and dad, and 2.5 children and a puppy and a fence and all that stuff. And my family started out that way until I was about three and my parents got divorced. They very much tried to fit into that role of a mom and a dad and two boys and one girl. And, you know, and I was that one girl. I don’t identify like that at all now, but it was always this is what you’re supposed to be and this is how it’s supposed to be and this is who you’re supposed to be.

But that was pretty much severed when I was three and my dad was gone and we had moved to Southern Idaho for a little while and came back into Northern Idaho. I just remember feeling like…I never felt like…first of all, I never felt like what people expected girl to be. We were also very poor. It took a while for my mom to get a job, but she did get a job, but still raising three children on one job (a secretary type job) is not easy. I didn’t have a lot of supervision growing up either and we moved around a lot and sometimes we didn’t have a place to live. So there was a lot of bouncing around and a lot of trying to figure it out — how to be, where to fit, who am I? And sometimes that feels very selfish to even think that way, but I think about these things as a way to see the rest of the world.

I see my role in the world as being more of a helper type person; a protector and a helper. Some of that came about needing to protect myself because I was very much…I looked like a little boy. I was a tomboy and I got a lot of flak for that, for not being feminine enough. And I wasn’t able to be masculine enough, whatever that means.

I started breaking norms pretty young, like playing boys baseball. I made the boys baseball league as one of the first girls in my town to play boys baseball. And it was met with hostility from some people, and it was met with support from other people. I was fortunate. My mom was real supportive of that. Mostly I was looked like as a kind of a freak and anomaly and a weirdo, but I played and I had a good time and it sort of set the track for me to continue doing things that felt true to me. I got enough support to be able to do that. I think that was one of the early factors that helped me do that.

I can’t say in the whole world, but in Portland, in the United States, in Western civilization, the patriarchy is all of who we are.

SP: That’s incredible. It sounds like both you and your mom were doing amazing things — pushing boundaries and raising three kids while working.

DS: Oh my god, working a full-time job, three kids, and not always having a place to live. Yeah, it was rough.

SP: But you also mentioned that you were receiving all of these messages — the sense of norms and of not being enough — especially around like gender roles and expectations. Where was that messaging coming from for you?

DS: Yeah, around gender roles and expectations… I always wanted to be outside playing, playing football, digging in the dirt. I remember once, specifically in third grade, all my friends were out playing horsey. That would mean that one girl was, you know, running around the field and making horse noises. And another girl was following her, trying to catch her and tame the horse. The boys would always come around and chase the girls and they would giggle and I ended up being the protector of the girls. I was like the cowboy who protected the girls from the boys all the time. So I was always somewhere in between girls and boys doing something.

I didn’t make enemies from that necessarily, but I definitely opened up a lot of questions for other people. People would always ask me, are you a boy or a girl? Like constantly, are you a boy or a girl? Sometimes I would answer boy. Sometimes I would answer girl. And sometimes I would chase boys and punch them for asking me.

SP: This is going a little off of the things we discussed beforehand, but since it’s come up twice now, can I ask for our listeners how you see yourself today?

DS: Sure. Today I see myself as a non-binary person. I’m really, really grateful for that; the ability to categorize myself that way now. When I was growing up, that’s not even something that we were told was… I didn’t even know it existed. I didn’t even know it was okay to be either or both or neither, you know, and that’s how I see myself now: either, or, both, and neither. Sometimes I do see myself as neither. Sometimes I see myself as both. It can go back and forth very quickly, but mostly I see myself as sort of a non-gendered human being who gets to be okay with an X on their gender marker.

I got my first X on my gender marker a couple months ago when I replaced my ID and I could, if you want to know, I could tell you a little bit about how that happened.

SP: I’d be fascinated! And congratulations on getting the X.

DS: Yeah, I was excited about it. For a little while I didn’t want to because with the former administration I was really afraid of what that could possibly mean, and it still could possibly mean in the future. But I’ve got to be me, and that F did not work for me.

So the thing that helped me really, really, really embrace my gender was not too long after. I embraced a part of my sexuality that was in my sexual identity, which is kink from the kink community (the leather community). In my first relationship in the leather community, my person that I was involved with at the time started introducing me as he, to all of her people and designated me a ‘boi’. It just fit, because I knew in that world, boi, as in b-o-i meant someone with an AFAB body (Assigned Female At Birth body), but with a gender designation that was a lot less definite. I could have my body still and be who I am still, but be called a boi which just fit. It fit my clothing. It fit my style. It fit my sense of self.

And so I started playing around with the clothing that I wanted to wear. And I now have a style that started… that was back in 1998 and ‘99. So that I went down that path and I was already what— 35, 40, but the cool thing was that when I started being called ‘boi’ or with masculine identifiers, it was like… oh. I didn’t want to always be one or the other necessarily, but it really opened my mind up to it. And then a few years later non-binary stuff started coming into the picture and I knew that that was even better.

The first instance of the more non-binary stuff, honestly, was from a friend of mine who was part of the Naraya group. It’s an honored tradition with a lot of non-binary folks, two-spirit folks that go to the Naraya dances, and the person I was dating at the time was involved in that. We talked a lot about two spirit, and then I ended up writing a paper on it for school. I fully admit that that’s not my culture and so I don’t want to take anything away from that at all. Just in saying that to take away the shame of feeling like that my gender didn’t fit anywhere when there are cultures that it’s always been part of, you know…just not ours. So I felt really relieved about that and I was able to translate. And then I started looking for places and other people who accepted me or even championed the non-binary world, the non-binary identification, non-binary embodiment. And I know right now that trans folks — especially trans women of color — and trans folks everywhere are getting a lot more flack and trouble than we used.

SP: Thank you for sharing all that. I am so grateful that you found the language that helps you know who you are and feel powerful in that.

DS: Yay! Thank you. It’s really interesting to me because I treasure so much the people coming up in the world because it’s the people coming up in the world who… I’m almost 58 years old so I treasure the younger people coming up in the world who are so unapologetic about who they are. It makes me almost cry, you know. Like my partner’s kiddo is a non-binary kid, a non-binary queer kid, and they’re only 14 years old and they’re….I just want to cry because I’m so happy that there’s a place for people in the world. There’s lots of other things to worry about for them and for younger folks who are non-binary and are coming out in the world, but that is one struggle that’s getting some attention and getting some traction and some support that I didn’t get before. It just makes me so happy.

SP: It’s amazing to see, isn’t it?

DS: Yeah, it really is. Oh my gosh.

SP: Okay, we’ve spoken a little bit before about mental health struggles that you faced as you were growing up, specifically in your thirties. It’s okay to get as into this or not into this as you’d like to, but if you’d be willing to share a bit about what you were experiencing and the ways that patriarchy was impacting you, I’d love to hear.

DS: It’s hard to talk about sometimes, but when I first came out when I was 19. I thought, oh goodness, yay. I came out so the world’s going to change. It’s going to be different. That’s what was wrong with me. In my head I thought that’s what was wrong with me: I was gay, so I came out in the world and I thought it was going to be okay. But the world that I came into was a world of stereotypes and a lot of patriarchy in the community that I was in.

There was Butch and Femme and you had to be one or the other, and nobody could be out and gay. We had these small communities of people in these secret parties, because in a place like Lewiston, you can’t just go meet at a bar or something like that, or just go to have coffee someplace because people get hurt for things like that… And they did, I actually had a friend who was killed for being gay, basically. I don’t want to bring all that into it, but it’s true. It was not okay to be gay. It was not okay to be different.

I could have my body still and be who I am still, but be called a boi which just fit. It fit my clothing. It fit my style. It fit my sense of self.

And even in the gay world, it had to be masculine and feminine together. I mean, there were people who weren’t masculine or feminine looking, but had masculine or feminine roles. It’s so hard to talk about sometimes because we’re talking about me, but it’s not about me. It’s about growing up in a culture where there’s no room for you to be anything, but what they want you to be. You know? And I must say the people around me were all like, oh, that’s just Domi. That’s just Domi. It was so dismissive usually, everybody just wanted to push it away…until I went to the hospital.

I ended up going to the hospital for 30 days and was diagnosed with depression and PTSD. So I do have some pretty significant mental health stuff going on, but over the years I’ve learned how to deal with it and learned how to get the support I need when I need it. And the thing that’s helped me more than anything the past 10 years is writing and the writing community. And I just dove right into it when I found this group of people here in Portland.

SP: Thank you for sharing. I know that today you’re one of the key contributors to Corporeal Writing which an absolute pillar of the Portland writing community. They’re fantastic. Would you be willing to tell listeners a little bit about what Corporeal Writing is and what you do there?

DS: Sure. Corporeal Writing is an idea and the practice of recognizing that the body has and holds our stories. Whether we can articulate them or not through words or through whatever kind of art, if we can find a way to tap into what our body has to tell us, we can get things that are locked in there that we might not even know about. We actually have a physical space downtown, and I’m the manager of that space, but my initial role originally, was just helping Lidia get it started.

So Lidia Yuknavitch is the founder and creator, and I’m not necessarily the co-founder, but I helped start it. We call it different things at different times, and she likes to give me credit. I did help her start it because I 100% percent believed in what she was doing, and we tried to build something that would really, really help people who might not necessarily fit into other writing structures or other writing practices. The true belief is that everyone deserves to have a voice. And what I see my job as is I want to help you mine your words. I want to help you find your words. I’m not here to tell your story. I’m not here to tell you how to tell your story, or even how a story should look.

This is how I think Corporeal Writing fits into bringing down the patriarchy. We don’t talk about bringing down the patriarchy, it’s not like we’re having conversations all the time about bringing down the patriarchy, but our actions encourage people to really find the way that they want to create their stories and how they want to put them out in the world. It doesn’t have to follow any kind of arc. It doesn’t have to follow a linear storyline. It doesn’t have to follow any theories necessarily. We give them as much information and as many resources and encourage folks to access what their body stories are and what their bodies are trying to tell them. And it’s just beautiful to see what comes out of people.

The true belief is that everyone deserves to have a voice. And what I see my job as is I want to help you mine your words. I want to help you find your words.

SP: It almost sounds like you’re back in that protector role again, helping to make sure that all these authors get to write what they need to write.

DS: Absolutely. One of my major roles there is a holder of space. You’ve got to be able to hold the space for people in order for them to feel comfortable and safe enough to go to the deeper places, to get to the work they really want to write. I try to do it safely, to encourage folks to have people they can talk to and stuff like that. But yes, the protector role is definitely very much part of my job.

SP: You’ve already spoken a bit about how patriarchy puts restrictions on people in terms of their ability to tell their own story. Is there more that you’d like to say on that? And how does colonialism get into the mix?

DS: Yeah, I want to say one of the ways that colonialism gets in is because we are taught that there’s a way to write. We are told that the market wants to hear certain stories and certain stories get elevated above other stories. It is no surprise that the canon is filled with old white dudes and it’s okay, but there are other voices that are really, really important to be heard.

How do I say this? It’s okay to write books in snippets. It’s okay to write books in what you can come up with your own forms. I think the reason those things are happening is because people have pushed it and said, no, I’m not going to do it the way you want me to anymore. I’m going to do it like this. And there are people from other cultures like this is the way we tell stories in the culture that I grew up in.

In my own personal culture, my family culture, the way we tell stories…there’s a lot of joking. There’s a lot of ribbing. There’s a lot of short, anecdotal things that happen. And it comes out in my writing, so I’ve learned how to write another way. I’ve learned how to write a linear story. I know how to have rising action and the climax and the denouement and all that. I know all that stuff, but do I want to write that way? Not always.

SP: You were saying that it’s important that we start listening to other voices — which I completely agree with in literature and frankly, every other aspect of our culture — but what would you say to folks who are worried about maybe losing their spot at the table?

DS: Honestly, what I’ve done and what I would continue to do is I would move over and give them my spot.

If you’re afraid of losing your spot at the table, let me roll back a little bit and you take the spot and I’ll listen. I very much advocate for us to elevate other people’s words. I think what I’d say is take your spot at the table and don’t let these people push you out, and if there’s any way that I can help you I’ll do it.

SP: But your voice is important too. How do you find that balance between representing yourself and working to elevate others?

DS: That actually has been kind of a problem for me, so it took me a minute to think about this, whether it’s time right now for me to say something and to put my voice out in the world. But the truth is I deserve to be heard too. I know that. There are very few people, very few subsets of people that I would say, now’s not your time to be heard. Just listen for a minute. But I will say that to me because I don’t want to be the center of everything while there are still other people who really, really need to be heard.

SP: That is so generous, but I’m glad that you’re part of this conversation too.

You’ve got to be able to hold the space for people in order for them to feel comfortable and safe enough to go to the deeper places…

DS: My thing is… people can make connections and be heard, if you set the stage right. I still have not figured out how to set the stage right, to get the right voices heard. I think that’s my drive and I’m not the one to even say what the right voices are, but I’m here for helping people whose voices need to be heard get out there. I just want as many people’s voices to be heard as possible. There’s no scarcity.

SP: Absolutely. Okay, so now that we are all caught up on your life, I want to do a check in and see how things are going today and how those patriarchal and colonialist influences are impacting you (if they are) and what that process of decolonizing your mind is looking like?

DS: The biggest way that the whole mess is impacting me right now is that I think that the financial disparity between the Haves and the Have-Nots is just ridiculous. I live in affordable housing, and it still is not affordable. The way it’s impacting me now is like on a very personal level…my mind is colonized by… basically if you live in this kind of housing, then you are worth nothing, you know? I don’t think that about other people at all, but when I think about it for me, it’s like, oh, you’re a loser for living in needing to live in affordable housing. I have this thing for my childhood — I wanted to grow up and live in a penthouse in New York city and be a writer — and because I didn’t follow the path that I originally started on, which was to be a technical writer or an engineer and I followed social work instead because that’s where my heart led me…I just struggle all the time with, well, if I would’ve done this differently, if I would’ve made more money and I struggle with that, my self-worth.

I mean, I know I’m privileged to live indoors. I know I’m privileged to have a place that’s accessible because I can’t walk. I know I’m privileged to have a car and to have people who care about me and to have food on the table. And, you know, it’s a bullshit story that the patriarchy tells us that we ought to be thankful for the little scraps we get. That’s what I’m trying to say.

SP: Yeah. That resonates.

DS: One of the things I was going to say too earlier is I that think like my mere existence as a queer fat poly kinky weirdo writer artist person who’s non-binary…just my mere existence is resistance. So I am inhabiting my body and being who I am and working very hard at becoming unapologetic about who I am.

If you looked at me on the outside, if you met me out in the world, you would think I’m very unapologetic about who I am, but it’s a practice. That’s why I think I’m just so in love with the younger folks that I meet; I’m just so happy that that there’s a place for them. I want to support them being able to be okay with who they are too, because I’m not going to be around forever, obviously, but I’m so grateful that there are people who are able to be who they are at a younger age than I was.

I’ve gone a long enough span of my life. I’m not old, but I’m a little bit older. I can look back and say we have made some progress. All that means is I see some younger folks who are identifying more and more of the problems we have and because we can actually start wading through stuff now, because we can see 1) that people like us exist 2) how can we support each other and 3) what needs to change. The existence of this podcast is testament to that.

SP: Out of curiosity, what does need to change in your opinion? If you had a top bullet points — 1, 2, 3 — what do we change?

DS: 1) The devastation of late-stage capitalism. 2) Decentralizing information and 3) Figuring out how to network with each other.

I think the other thing is supporting the hell out of artists and people who don’t have a voice or who don’t have enough of a voice. There’s some really cool work coming out and I think if we just pay attention to the people around us who are trying to create things that show what their world is like, to show who they are, we get a greater understanding of each other or at least a little bit of compassion for one another.

SP: Wow. That is an excellent checklist. We’ve just got to take care of late-stage capitalism, decentralize information, and support artists.

DS: Yes, perfect! Thank you.

SP: Of course! Before we wrap up, I want to get to some more exciting recent news assuming it’s still okay to share.

DS: Yes. It’s okay. Share.

SP: I recently learned that Domi is engaged to get married soon!

DS: I am, and what’s really funny is for years and years and years, I haven’t been desk pounding against marriage, but…I’m not a huge supporter of marriage generally. Or I wasn’t, I should say, because for so many years we couldn’t get married. And now, it’s like we want to be like heterosexual folks and get married to take on their traditions, and I have to say come on, Domi, just relax. It took me a little bit to be okay with it, and then when I was okay with it, my partner has historically not been okay with it either. So when I asked (a couple of times) I did it sort of theoretically. It was hilarious. Like sort of theoretically, like what would you do? And so we had the conversation about the philosophy of it more than anything. What I’ve decided, and I think it’s part partially because of COVID, is my shoulders need to drop a little bit. I need to take a breath and be like, this is what I want. I do want to be married to this person.

Then on top of that, we’re buying a house, which I didn’t think I’d ever do (my name on the title and everything) because I also have some weirdness about owning land because we can’t really own land and I’d just been so against all that for so long. But was I against it because I could never attain it because I grew up so damn poor? Did I really choose not to be as capitalistic as I could have been by working in jobs that didn’t pay a lot of money? There’s all kinds of questions around that, but point is yes, I’m getting married and getting a house. It was not an easy decision, but I’m very, very, very happy about it now!

SP: I am too! Listeners can’t see it, but I have a huge grin on my face as we’re talking about this.

DS: Yay! Thank you so much, Sam. And thank you, Amy, for allowing me to be here.

SP: I’m so happy that you joined us.

Learn more about Domi at corporealwriting.com and domishoemaker.com

here’s some good news:

we can change this system

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!