“…we can do something, one step at a time, to help each other to survive and thrive…”

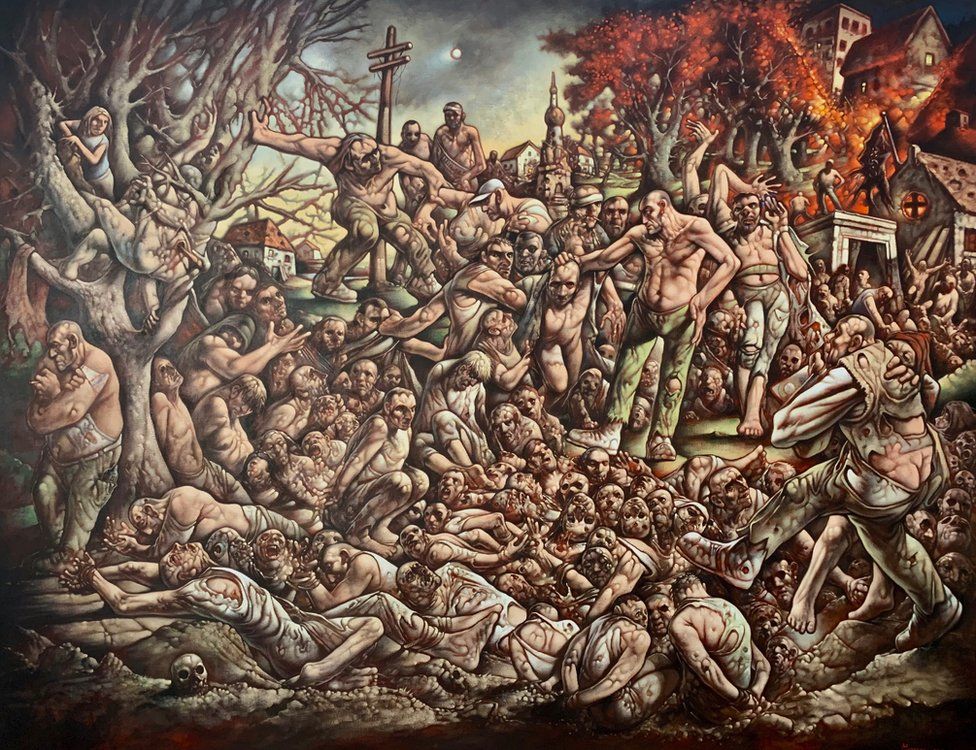

Late in March in 1991, years of rising tension between Croats and Serbs erupted into violence when police and soldiers opened fire on civilian dissidents, resulting in what many agree were the first two deaths of the Yugoslav Wars. In the years to follow, tens of thousands more would lose their lives in a series of conflicts across the region.

On today’s episode Amy is joined by the brilliant Dr. Beverly Allen for an interview about her experiences studying the treatment of women and the roles that patriarchy played during these international wars, as well as the ramifications that her discoveries still hold for us today.

Please note that this episode contains some challenging content— during our interview we discuss forms of violence, including the use of rape and torture. Take care of yourselves accordingly.

Our Guest

Dr. Beverly Allen

Beverly Allen (she/her) has taught at Cornell, UC Santa Cruz, and the University of Zagreb. Her books are in Italian Studies and Cultural Studies,

including Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia.

Recipient of numerous awards and prizes, she held the William P. Tolley Distinguished Teaching Professorship in the Humanities at Syracuse. She received a Masters from Columbia University and a PhD from UC Berkeley.

The Interview

Amy Allebest: I always look up my professors before the very first class and see what they’ve done in the world and who they are. So, I had seen your bio before I started your class, and I was really intrigued about your work in Bosnia and Croatia, and the book that you wrote about rape as a weapon of war. I thought it was interesting that a professor of literature and languages had contributed and made such a huge and meaningful contribution in this topic that seemed kind of like a different field, like more sociology. Maybe that would be a way into our topic, because I had wanted you to talk today about your book, if you’re willing, and about your experience in Serbia and Croatia and what that has to do with patriarchy. So could you just lead us into the topic by telling us how you encountered this topic in the first place?

Dr. Beverly Allen: Absolutely. You know, I agree that it seems unusual that a literature professor should become interested in and work in this topic. It happened at Stanford. I was teaching a course on the history of Italian literature and, of course, when you teach such a course you have to provide a critique of the canon. How do we decide what constitutes national literature? It’s a huge cultural operation, you know, and it’s got a traceable history, and a history that is in fact ideological. So one of the things we do, one of the things I do, is talk about the lack of female writers in that canon. Very, very few. It became a course that incorporated feminist theory. One of the students in this class, a young woman, she is Croatian with Bosnian heritage. She discovered feminist theory in that class and became deeply engrossed.

The following summer, I think it was summer of ’92, I was at home and she asked if she could come over. She brought with her a stack of testimonies by girls and women who had survived what we later came to call ‘rape death camps’. She had gotten these from the Croatian Information Office in Los Angeles where they had been translated into English so I could read them. I started reading them and I didn’t believe them. I thought, no this is propaganda this this can’t be true, and they sounded so similar to each other… I was very suspicious. Deeply. I was unwilling to live in a world where things like this were happening.

Something happened when I was reading those testimonies, and they were all signed by the way, something happened to me and my disbelief snapped into belief and the instant that it did, I saw that I needed to stop this. This is how it started for me. I needed to stop these rapes, these rape camps. It didn’t occur to me that I couldn’t. So the question was what do I do now? The first step was to contact a journalist at in New York and who I happened to know—she was married to a colleague in the French department at Columbia. I told her what I had learned, and she said that a colleague of hers, Roy Gutman, was in Bosnia and had heard rumors about these places, but he had no evidence and could I please, at the time fax, these copies to her and she would get them to Roy. So Roy got these, and that enabled him to write the first article that appeared in the United States, in the Washington Post in fact, about rape camps in Bosnia run by Serb nationalist militia and soldiers. He kept with that story and later won a Pulitzer Prize for it, and I got to meet him and, “Oh you’re the one who faxed those?” he said.

Bosnian girls and women were being rounded up from villages, and taken to restaurants, or schools, or hospitals, or hotels and held for months and being tortured and raped on and on and on. I saw that if they got pregnant, they were kept alive. If they didn’t get pregnant, they were often executed. If they got pregnant, they were held and continually raped until the pregnancies had gone past a point at which abortion would be possible without killing the mother. That, in the eighth or ninth month of pregnancy, meant that the Serb nationalist captors—who were often militia but also often regular soldiers in the then-called Yugoslav National Army—they would let the women go and that meant running into the woods and trying to make their way into the refugee system and hopefully getting to Zagreb. I’ll explain some of this later from the woman’s point of view. Getting to Zagreb meant getting to the Rapcha hospital which had treatment for them.

So you see, it doesn’t matter that I learned—you don’t have to figure out how to solve the whole problem. You just have to figure out the next possible step, the next step you can take. And so another interesting thing happened during this period. I remember being at the Stanford shopping center, and you know how elegant and high-end that is. I had stopped at a little café, it was early in the morning somehow, and I was sitting at a table outside having a cappuccino. At the table quite near mine, here were two men dressed in suits and one looked European to me.

I was very suspicious. Deeply. I was unwilling to live in a world where things like this were happening.

I’ve spent a good part of my life in in Europe. My family is from Sweden, and I’ve lived in Sweden, I’ve lived in Italy for 13 years, I had spent time in the former Yugoslavia, France, Greece… I’m familiar with some signs of Europeanness, perhaps is a way to put it. I had a strong feeling that one of these men, the older one, was European, and the younger one looked to me like some kind of American government official. Now, this is a total stereotype. You know, he had a buzz cut; I mean he just looked like some government guy. Well, then I heard what they were saying. And they were arranging for the wealth of the older man to be transferred and cared for by the US government so that he could stay away from Croatia, and that’s when I learned he was Croatian.

I was reaching the Stanford shopping center. I remember coming out of a concert on campus, and it was a beautiful summer evening, and I heard some young people talking about the rapes in Bosnia. They had heard something somewhere about snuff films, and I thought my god you know I’ve got to find out what is going on. Well, one thing to do when you’re trying to figure out the next step to take is to look at the options you do have. And one of my options was to apply for a grant to translate Italian poetry in Venice. I applied for that grant and I got it and I knew that this would be probably the closest I could get in Italy to Zagreb, where I might be able to meet some survivors and try to understand what this was. Really I was still doubting a bit, still hoping that the world didn’t have such horrible things in it. So I got to Venice, and the wife of a poet I’ve written a book about took me to a literary luncheon and sat me next to someone who ran the Italian Institute of Culture in Zagreb. He was having a very hard time getting speakers to come from Italy, because every now and then Zagreb would be shelled, but I couldn’t wait to get there.

AA: Oh my. You weren’t scared?

BA: No, no. I don’t know why.

AA: Yeah, I was going to ask why, but you just were— you felt you had a mission?

BA: Absolutely. Now as a former Mormon you would understand that.

AA: Wow and I guess yeah, you felt called by something. I do understand that.

BA: I felt definitely called. There was just no alternative. I had to do this. So, one day I got on the train from Venice to Zagreb, and at each stop along the way it became more and more clear that I was the only woman on the train, that we were going into a war zone, that I was a suspicious character. Even though, you know the hardest question for me was what am I going to wear? What am I going to wear at the war? And I thought, well I want to be very respectful of the people I meet, so I decided I would dress as well as I could, like some of my best teaching clothes.

And that turned out to be a very good decision. A very good decision. Because, after all, I was going to a city that considered itself a major European capital and in many ways is. I gave a lecture on behalf of the Italian Cultural Institute in Italian, and about 300 people came. Now, during the war, people lack things to do, you know, it’s boring. But many of them understood Italian because of past history, and so they did come. Among other people I met a journalist and editor, and they asked me to come with them the next day to a book presentation in Karlovac, which is a city that was on the front line. And I did that, and bit by bit… I mean that’s a whole other story.

…my disbelief snapped into belief and the instant that it did, I saw that I needed to stop this. This is how it started for me. I needed to stop these rapes, these rape camps. It didn’t occur to me that I couldn’t. So the question was what do I do now?

I’ve got to tell you, war, I learned— there’s something attractive about it because it makes everything very clear. When you’re busy surviving, you don’t have time for a lot of neuroses, although it creates neuroses later. Anyway, that’s one of the secrets of war. It’s very dangerous that way. I’ve been essentially a pacifist all my life, but one day I was in Sarajevo, and this was just after the war had ended, and it was kind of a scary place because there was a lot of anger and disaster and trauma, and you never knew who was going to explode or whatever. I’ll never forget how, when I saw a UN armored car I felt, “Oh thank goodness.” You know, I was grateful. So that’s another story. War itself creates this world that is different from daily life in peacetime. So maybe that’s an answer to your question: how did I find out about it, and what did I do?

I continued to volunteer to teach at the Syracuse University Campus in Florence, and from there I could take the train to Zagreb and continue my research. I took an extra leave of absence. I lived on half salary. Whatever it took. One day I was speaking about what I had been learning mostly in Croatia, because that’s where I met survivors. At the University of Florence, I was sitting on a panel and next to me was an Italian journalist who had written about what he had learned in Bosnia. I said, “You know, I think I need to write a book too, but I don’t know how to start it.” He had seen me jotting little notes on the back of an envelope for how I would speak that day. I had just written down, you know, topics that I wanted to cover in my brief talk to about 150 political science students at the University of Florence. When I said to this man sitting next to me, “I don’t know how to start,” he looked at this ratty little envelope and he said, “Well, that way.” And so when you read my book, you’ll see, it’s divided into topics. You know you can do more than you think you can.

AA: Is it divided into envelope one, envelope two, envelope three?

BA: Yes! But I don’t say that.

AA: That’s really inspiring. It really is, through that whole story—one thing I’m going to take away from this conversation is that exact point of what’s the next step, what can I do? Because I think so many times we don’t do anything because we’re so overwhelmed by how depressing it is, and what a huge issue it can be, and we just get… it overwhelms us to the point of paralysis. So then we think, “Well, I can’t solve the problem, I can’t even talk about the whole problem, so I guess I won’t do anything.” I love that you thought, “Well, I’ll just take this next small step. I’ll take the fellowship in Italy, then I’ll have access, then I’ll take the train over whenever I can, and I’ll write it on envelopes.” Then, I mean eventually it turned into your book. So keep going with your story, this is fantastic.

BA: Okay, well, I knew a woman in Florence who had started— she had founded the first feminist bookstore in Italy. She must have come, because I was giving talks in Italian and in English to different audiences. I had lived in Italy quite a while off and on, but for many years. I had been invited to join the Radical Party which was a trans-party party. That’s another great research project for young academics to look at what they did. In other words, that party called itself ‘the Radical Party’ because they wanted to get to the root of things. Radical in that sense. They promoted legal abortion, which saved many lives. They promoted divorce, which didn’t exist in Italy until sometime in the 70s, you know. One of their leaders, she was headed to the UN. I was back at Syracuse by then and she learned about my work. She asked me to come and meet her at the UN, and I did, and she said, “What can we do for you?”

You know, I’m going to take a parenthesis here. At some point in my spiritual journey I thought I could be Episcopalian, and I remember having lunch with an Episcopalian dean in Syracuse. He was dean of the cathedral and he wanted to know about my work in Bosnia. I went and I told him what my beliefs were, and discussed metaphor and symbol, and this and that. I said, “So, I don’t know if the way I understand Christianity qualifies me for being an Episcopalian.” And he said, “Well, Beverly, perhaps the better question here is what can we do for you?”

AA: Oh wow.

BA: Oh, my heart melted. You know, it melted. This woman said, “What can we do for you?” and she said, “Okay, when you go to Rome, you go to this journalist and that journalist if you need to.” I later needed to do research at the law library in Rome, and they— also everyone that I needed help from was a member of the Radical Party. That was because you didn’t have to quit any other party you were in to join this one. It was really about getting down to the roots of things. So, back in Florence, I had met this woman who had the bookstore, and she asked me if I would allow her to bring a few friends, and would I speak to them in Italian? Yes, so one night I gave a little talk. There were very few people sitting around a table, maybe seven or eight, and one of them turned out to be Antonio Cassese, who was a professor at the European University, which was just outside Florence, and at the University of Florence. His topic is international jurisprudence, and he was a friend of the bookstore woman, and also he was the first president of the United Nations international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia!

So I gave my talk and discussed what I had learned and how I read it, how I analyzed it, and afterwards he said to me, “Thank you Beverly. Until I heard you speak, I didn’t know— I understood that there were two kinds of rape going on in Bosnia: the regular kind that happens in all wars, and something else. But I didn’t understand what the something else was until I heard you speak.” This man was sitting on top of all the evidence that existed at the time, and he hadn’t been able to understand the difference, and he said, “Please will you come to the tribunal? You’re writing a book. Please send the manuscript as soon as it’s finished so I can give it to all the judges, and please come and confer with our chief prosecutor, Goldstone.” And I said I would. You know, I want to get onto the topic of what the rapes were.

AA: Okay. If it’s okay to interrupt for a second Beverly, I’m just wondering if you could give us just a little bit of the lay of the land and back up just a tiny bit for listeners—honestly including myself— who maybe need a bit of a refresher about the conflict that was happening in the area. Who were the major players? Just briefly remind us of the years and what the conflict was about, and then yes, please tell us what you discovered as you did your research and then were presenting afterwards. What was happening in these countries?

BA: Yes, this is the hardest question to answer because I really could speak for hours to explain it. After World War I, Yugoslavia was divided into regions. Here’s how I see it: in the Balkans there’s the division between the Western Empire and the Eastern Empire. It goes back to the early Common Era. We have in the West the Roman church and in the East the Orthodox Church, and that division is based on a disagreement about what constitutes the nature of Christ. That’s another issue. Then we have the Ottoman Empire, which was this fabulous, powerful empire coming from Turkey and conquering everything that it could, including Serbia, what we now call Bosnia, and the Ottomans were encountering then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was Catholic. The Ottomans were Muslim. What we have is a sect developing in Bulgaria called the Bogomils, and these are Christians who are very pacifist, and they follow their missionaries. Their missionaries come across into Bosnia (again, what we call Bosnia) which had been conquered by the Ottoman Turks. Many Bosnians converted to Islam under the rule of the Turks. The Bosnians, the people who lived in that region, are no different from the Serbs or the Croats or any of the other regions of the former Yugoslavia. Genetically, it’s not a question of race, although it’s been formulated in those terms.

Under the Ottomans, a lot of Bogomils, these Christians in Bosnia who were not Roman Catholic, they converted to Islam because it made life easier. The Ottomans were taxing non-Muslims much more heavily than they were taxing Muslims. So these converts had formed a version of Islam that was heavily influenced by Bogomilism, and that meant that their version of Islam was pacifist. It was welcoming of others. It was non-proselytizing, and that tradition continued in Bosnia. Bosnia also invited Jews who had been expelled from Spain to come and live in Bosnia, and there’s been a flourishing Jewish community ever since. Now, post-World War II, Yugoslavia became a non-allied state. It was a communist state, but not aligned with the Soviet Union.

…there’s something attractive about [war] because it makes everything very clear. When you’re busy surviving, you don’t have time for a lot of neuroses…

The ruler of Bosnia, the president, whatever he was called, was Tito. Tito was very severe with regional nationalists. So if you were a Serb nationalist, you risked getting put in prison. He was very severe with homosexuals. He was very severe in those ways. However, he built a highway connecting north with south and he called it the Highway of Brotherly Love. He did everything he could to create a Yugoslav identity, which meant southern Slav. We don’t realize it from the outside but that was a novelty, because until then people had identified absolutely as Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian, Montenegrin, Macedonian… There was even a census where, if you were living in Yugoslavia, you had to say which one of these you were. However, the region of Bosnia contained everything. It was such a welcoming region. It was so integrated that there wasn’t a nationalist label, so they gave it the label Muslim, although that didn’t describe every Bosnian by a long shot.

Tito died in the ’80s and was replaced by a five-man presidency, but from the beginning Slobodan Milošević, who was the leader in Serbia, had plans to take over the presidency completely. He was already busy nationalizing the Yugoslav army and making it a Serb army. I met university professors who lost their jobs during the late ’80s because they weren’t Serb. So finally, one day, this sort of Yugoslav national army which was really a Serb nationalist army, made a deal with Slovenia, and Slovenia paid it off not to attack. With the money that the army got from Slovenia, they bought weapons and arms and attacked Croatia and massacred. Now, Croatia is heavily Catholic. Franciscan missionaries converted it. Let’s say it was— it’s very close to what was the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Then it started on Bosnia. I have a friend, she tells me she’s a writer in Sarajevo. She said, “We woke up one morning and we saw the army ringing the hills around Sarajevo. And we thought, ‘Oh, they must be doing some exercises,’ and then they started shooting us.”

So thus began the siege of Sarajevo, and there were a number of other cities that underwent the same siege tactics and suffered enormously.

AA: Can you remind us what year this was?

BA: 1992. Thus began the invasion of Bosnia, the Serb nationalist attack on Bosnia.

Now, Bosnia is a beautiful place, and it’s full of minerals, and had a great industry in herbs, and was valuable real estate. The Serbs have— Serb nationalists, this isn’t all Serbs by the way—but Serb nationalists have a creed that sees them as victims, and in particular it sees them as victims of the Turks. This goes back to a battle in the 14th century, the Battle of Kosovo, where Serb forces were defeated by the Ottomans. Never mind that there were Serbs fighting on the side of the Ottomans— I mean this is a nationalist rhetoric that begs all reason. It’s the power of the narrative. So Serb nationalists have developed a rhetoric of victimization. Their creed says that historically they have been victimized by Muslims, by Turks, by the Ottoman Empire, and this justifies any attempt they make at regaining territory. Now, we get to the rapes. Yes, there were what Cassese called regular rapes in war.

AA: What does that mean, what did he mean by that? Because there are regular rapes all the time.

BA: Exactly.

AA: But what did he mean by “regular rapes in war”? Just that there’s not as much policing, and so there’s more— whenever there’s a crisis, crime goes up because a) people are stressed and b) they can get away with more, is that what he meant?

BA: Yes, exactly. It happens in war that the soldiers have no accountability for any sex crimes they might commit. Until recently, there was no accountability for crimes against civilians for all sorts of other crimes. So that was going on, Cassese understood, but what was this other thing? Well, this other thing turned out to be a policy on the part of Serb nationalist forces, both army and militia. We discovered it in two sources: the RAM plan and the Brana plan. These were discovered surreptitiously, and therefore we have evidence that these forces ordered the use of rape as a weapon of terror. Their forces would enter a Muslim village. By the way, in the cities everyone was mixed with everyone else, and people were in so-called mixed marriages, although they never thought of them that way. I mean, under Tito people didn’t identify so much as Serb or Bosnian, they were just Yugoslavs, and they married each other. But a lot of these mixed couples had to leave. They were terrified of what would happen to them.

AA: And sorry, when you say mixed marriages too, you’re saying in general there were divisions, that like Serbs tended to be Christian? And who tended to be Muslims?

BA: Serbs were nominally Orthodox Christians, and the Bosnians tended to be Muslims, very secular, although anyone could be a Bosnian. It was just a very secular region, and most of Yugoslavia was very secular. It was communist, you know.

AA: Right. Okay, so when you say mixed marriages this meant nationality and religion, but prior to this time it mostly hadn’t been a big deal.

BA: It had not been a big deal at all, but now as the Serbs were advancing and killing people for being Muslims or Croats, that was their rhetoric. A lot of people became frightened, and they hadn’t thought of themselves in those terms before, and they left. By the way, the religious identity is a sham. I mean, it’s just a pretense for animosity. Most of these people didn’t care at all about creed or spirituality or anything that you might get from a religion. It was about identity, and they felt their identity was threatened, I suppose.

“We woke up one morning and we saw the army ringing the hills around Sarajevo. And we thought, ‘Oh, they must be doing some exercises,’ and then they started shooting us.”

The cities were very mixed in that sense. They were very secular. But there were still Bosnian villages where the people were mostly Muslim, and there were Serb villages where the people were mostly Orthodox Christian. Here came these Serb nationalist militias or soldiers, depending on their provenance, and they would come into a Bosnian village and get people out of their houses and maybe kill or rape a couple of people in the streets to terrify everyone. And often then they would round up the women and the girls and take them away in trucks to these places that were available like restaurants with several backrooms, or hotels that had been abandoned, or schools, or even hospitals that had been abandoned. They would hold them there and rape them over and over and torture them with things like electric hair curlers or irons. And if the women got pregnant, they would let them live. If they failed to get pregnant after a while, they would kill them generally by slitting their throats, because many of these soldiers were shepherds and that’s what they knew how to do, and they didn’t want to waste bullets.

So you have a terrible, terrible situation because then, when the pregnancies of these prisoners came to a place, like eighth or ninth months, where the women would die if they attempted an abortion, then their captors would let them go. And here was the policy behind it: according to Serb nationalist rhetoric, narrative, story, any child born with a Serb father would be Serb, and any child who was Serb no matter how he was raised would recognize when he reached maturity that he was Serb and would claim the area where he was as part of Mother Serbia. So the idea was that these women were containers for little Serb soldiers, and they heard over and over again, “Now you’re going to make a little Serb soldier. Now you’re going to get up to the Austrian border and your little Serb soldier will increase Mother Serbia.” They would release these women, maybe into the forest or maybe into a nearby town, and they met various fates. Some of them got into the refugee system, some of them got to the big hospital in Zagreb, which is where I learned most of what I learned. A couple of instances, I followed the suggestion of Muslim religious leaders in Bosnia and went home to their families where they gave birth to these babies and included them in their families, but not very many. According to the director of the psychiatric institute at Rapcha Hospital, the first thing the doctors had to do was treat women for suicidal tendencies, and if they survived those then they were generally homicidal or infanticidal, they wanted to kill these babies. This was a terrible thing for them to contemplate, most of those mothers just left the hospital and went out into the night, abandoning the babies in the hospital. Fortunately there were good orphanages and others took them in, but many children were born that way.

AA: Do we have a sense, Beverly, of how many women this happened to?

BA: No. Endless numbers. It has to have been thousands. I’ve been to a rape camp, which had been a restaurant, and I saw detritus, debris, women’s underpants. But how many of these women, then, if they survive and give birth and abandon the baby, where do they have to go? They have to go home to their village, or home to their family in the city if that’s how it happens. And they don’t want to be known as a victim of this or as a survivor. It ruins their lives to have that known.

Let me give you an example. The victim protection unit at the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, once they had arrested certain alleged perpetrators, needed witnesses and they had to keep these witnesses safe. So in many cases they arranged for a woman who had gone back to her family and didn’t want anyone to know what happened to take her children to school in the morning, be flown to the Hague, testify behind a screen so the alleged perpetrators wouldn’t see who she was, and be flown back to her village that afternoon and pick her children up from school. And no one would ever be the wiser.

AA: My goodness.

BA: So, thousands. Thousands.

AA: Beverly, I actually just looked it up really quickly. On Google it says estimates of the number of women and girls raped range from 12,000 to 50,000. Does that check out with your research that you did as you were writing the book?

BA: Nothing surprises me. I mean, rape was common in the war on all sides. However, this policy increased the number. Sometimes Serb soldiers refused to do it and they were shot. Now we need to remember a few things: one, that these actions not only harm the women but they harm the perpetrators.

AA: There were probably young boys, I mean, teenagers or young men…they don’t even have a frontal cortex developed yet to be able to make rational decisions, and they are being basically brainwashed by their leaders, right?

BA: Yeah, of course and the role of alcohol is also extremely important. They drank a lot.

AA: Yeah, I was going to ask about that, Beverly, because I was thinking that— we’ve talked about how patriarchy hurts women and men, and sometimes that’s because there’s a small group of men that decides what’s going to happen for everybody else, and that includes women and all the other men, right?

Who were the players? Who are the people at the top of this structure that were deciding to use rape as a weapon of war, and how did they brainwash— or maybe you wouldn’t say they did brainwash. But how did they convince all of these other men? You just said that some of them were shepherds. Some of them, no doubt, were young men, and I feel like they’re just being indoctrinated into this horribly, disgustingly violent thing. How did they get that control? How did patriarchy play into all of this?

BA: Well, from birth. You know, Tom Miller was the US ambassador to Bosnia at a certain point after the war, and I got to know him and his wife. She was a therapist and she wrote a series of books about parenting, just with drawings, not with language, and she thought that would be one little step toward getting people in that region to teach their children at a very young age how to be kind to each other instead of hitting and yelling. Patriarchy isn’t a decision, as far as I can tell, made by people in power. It’s what is normal for them, normal for men. But I think there are also women who have power and take on aspects of patriarchy.

This may not be entirely in order, but I want to say a few things about this that I learned from working there. Patriarchy, when it’s well in place, can also protect women. For example, in the village cultures, there was almost no rape prior to the war. Why? Because the women were possessions of their male relatives and if someone from another village were to come and kidnap and rape a woman, a girl, her male relatives would go and kill him. So there was protection against that sort of thing. Now, this doesn’t even begin to get into marital rape.

AA: Meaning that a husband could rape his own wife, but he would never let another man rape his wife, correct? Because that would discredit and dishonor him to have his possession spoiled, right?

BA: Right. Another fact I learned is that as Serb soldiers returned to Serbia, the incidence of domestic violence went up 200-300%, so they couldn’t just shed the behavior they had been ordered to do. Now, Sue Grand has written a remarkable book called The Reproduction of Evil. I think that there might be a good explanation for you, Amy. I don’t know that it’s the full adult development of a frontal cortex that would prevent patriarchy.

AA: Ah, no— I would agree with you there.

BA: Yeah, patriarchy is systemic like racism, like classism. Now Sue Grand says, and this is giving the benefit of the doubt to some perpetrators, the first time someone, we can think a soldier, is ordered to do something that absolutely short circuits his sense of morality. He can barely stand to do it. I mean, he does it on pain of death. Now he’s ruined his circuitry, let’s call it, and seeks a way to feel better about it. And the way he feels better about it is to repeat the act, and he repeats it, and repeats it, and repeats it so that it becomes normal. This is normal. This is what we do. Patriarchy is, as far as I can tell, not something we choose to tap into. It’s something that is fed into us, and that means men and women, and it robs us of what I call the sacred feminine. Now, I don’t want to sound like a broken record here. My friend Paul Robinson would probably say, “Oh that again, Beverly?” But from what we know, original sacredness was associated with feminine bodies and reproduction and a cycle of life, and it was gradually displaced by masculine prerogative. The ultimate example of that prerogative is femicide. Please look at Diana Russell’s book, Femicide. I think she introduced the term, the idea that killing a woman simply because she’s a woman is normal.

One of the most recent examples of this is the disappearance and murder of First Nations women. There are examples too numerous to mention. What happens on the southern border of the United States, what happens in sex trafficking. The way I think about it is that patriarchy is at its bottom, power, and with any power comes fear. To exercise power, one has to instill fear in those over whom one has power, but the holder of the power is also fearful of losing it, and will resort to whatever means necessary to keep it. I think it’s very important to notice that, in many ways, women constantly accommodate patriarchy, because the payoffs can be great. They can be great. We modify our bodies to accommodate patriarchy. We give up our dreams to accommodate patriarchy. We accept all sorts of things that are quite harmful to us in order to accommodate it, because we fear that power. But all the work we do to accommodate patriarchy doesn’t save us from the patriarch’s fear of losing that power and, so, the patriarch fears us.

There have been many different explanations of this, but we could go back to the earliest epic, which comes from ancient Sumeria, where the male protagonist is the founder of a city. This is related to urbanization, whereas the sacrality of the feminine is related to the land and agriculture. He besmirches the goddess, he insults her, and we go on through thousands and thousands of years of having the goddess broken up into many goddesses. You can’t have one all-powerful feminine symbol of this life cycle, but instead you have one who’s the goddess of wisdom, one who’s the goddess of love, one who’s the goddess of whatever it is. Finally, perhaps a recent version of a story of balance between sacred feminine and sacred masculine, which would be Yeshua and Magdalene, gets undone by the early Roman church, which of course takes all its structure from what it knew, which was the Roman Empire. It can’t stand this balance. So instead of allowing Magdalene to be a co-teacher of Yeshua, which she most likely was, they make her a prostitute on very flimsy textual suppositions, and then they are bereft of the feminine. The early Christian church, especially after the Council of Nicaea, is bereft of a feminine symbol, but people want that still. So they make Mary the mother of Yeshua, or Miriam the mother of Yeshua, the feminine aspect of the holy, and they make her holiness unattainable. They make her a virgin, and between the denigration of Magdalene and the virginity of Mary, female sexuality becomes totally demonized. The female association with the earth and growth and the cycle of life gets women burned at the stake in the European Middle Ages. They know plants, they know herbs, they know how to heal, and they are called witches, and men take over that activity and modern medicine is born.

Now, you don’t have to be a female to represent the sacred feminine. I personally think that Yeshua or Jesus is an avatar of that. So are you, Amy. You know, Derrida teaches us that you can be in a system and still perform a critique of that system, an analysis of that system, as he did certainly with language. That’s the big feminist takeaway from Derrida’s philosophy as I understand it. It’s very important for us to do what you’re doing. To have the conversations, to think about it, to notice it, and to see how it— you may be tired of this word already—but how it intersects with racism, classism. You know, the feminine is so demonized in patriarchy that anyone who is powerless is essentially feminized. Persons of color, persons of non-cisgender identity, people who don’t follow the norms of the patriarchy are viable targets for it, because they are feminized, and femicide is the ultimate goal of the patriarchy. Now, I can introduce you to my son who’s not like that. Not all men are like that, but it’s patriarchy.

I guess the point I’m trying to make here, Amy, is that there’s no decision to be made by the upper echelons of men in power. They know, let’s say in quotes, “naturally” what to do. And that’s because they are created by a system that has been developed over millennia. But, there is an underground river of the sacred connected to life. By sacred—I’m not using the word divine because I think that’s up to you— but sacred, something that is not the normal humdrum every day, but something special. This underground river of understanding that it takes starting from something like nurturing, starting from something like love to promote and participate in the cycle of life. So that if you want to embody the principle of the sacred feminine, you respect development, you respect emergence, birth, you respect growth, you respect— how can I put it? Helping. You respect shaking responsibility, you become responsible. You accept that your own body undergoes a cycle, and things aren’t scary anymore. Death isn’t scary. It’s part of it. It’s a mystery. It’s sacred, and in our understanding, as we live like that we can do something, one step at a time, to help each other to survive and thrive, and eventually we have to let go of patriarchy. That’s what we’re grappling with now, with climate change. We have to shift. It’s a very exciting time to be alive.

AA: Well I love that you say that at the end, because I was going to actually ask you as one last question: you started this conversation by saying that when you first read the accounts of what was happening in Croatia and Bosnia that you didn’t want to believe it was true, because you didn’t want to believe that things like that could happen, especially that could happen in your lifetime, in the late twentieth century, right? And then you discovered that it was true, and that this absolute horror was happening. So my question is, knowing that that very virulent embodiment of patriarchy, or that that very virulent version of patriarchy still can happen— and we’ve talked a lot on the podcast before about how there’s violent, toxic, terrible patriarchy, and then there’s also benevolent patriarchy where there isn’t denigration or disdain for the woman but just protecting and coddling and then keeping in the gilded cage. That’s a different topic altogether. But knowing that this horrible, really, truly misogynistic patriarchy can still happen, how can we say it’s a wonderful time to be alive?

How can we feel any hope, knowing that these things that have been happening for thousands and thousands of years keep happening and that— honestly, sometimes I think it’s so discouraging, too, because men are typically, bigger and stronger, and have basically a weapon. I mean, that’s why rape can be a weapon of wars, because if they choose to use their anatomy as a weapon they can, right? And females are just susceptible to that, and so they have all of these things that can be used against women built into them. Then there’s this systemic patriarchy, and then typically men have guns, or they have knives or they have weapons. It’s just… women don’t stand a chance, to be honest. Anytime there’s a bad guy that wants to get in power, and then get a bunch of people, they can destroy the lives of all the other men and the women and every and all genders, and sometimes I feel so discouraged about that. Because like you said, there’s something about it that has been with us for all of recorded history in our humanity. I have an idea of what my answer would be to this, but I want to hear what your answer is. How can we feel hopeful in the face of that?

Patriarchy isn’t a decision, as far as I can tell, made by people in power. It’s what is normal for them, normal for men. But I think there are also women who have power and take on aspects of patriarchy…

BA: Well, first of all, I don’t agree that it’s been with us since the beginning of humanity. I think there was something else, initially.

AA: Well I did say recorded time.

BA: Okay, yeah. A lot of women fight back. A lot of women use weapons. A lot of women find ways to escape— I’m thinking of domestic violence in particular— there are safe houses. Women are now reporting rapes more than they did before. But when I say this is hope right now, I’m not saying this is a fun and pleasant time to live. I think it’s a very difficult time to live, but in my lifetime we have not had the climate disaster that we’re having now, so something is being revealed. The earth is revealing to us that we will die if we don’t nurture it. Already we’re in a realm that’s associated with the sacred feminine.

Do everything you can to keep unveiling, unveiling, unveiling the disasters of this unbridled reach for power, which we associate with patriarchy. And, according to students I’ve had from villages in Africa, matriarchy does the same thing. We don’t want that. We want a joining, you know, we want to get back to first principles. Do everything you can. I’m retired now, and what I’m doing is talking about this sort of thing whenever I can. You can see a little slideshow I gave on the history of the sacred feminine at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Berkeley website under their learning personal theology section. It’s called “The Snake in the Grass.”

AA: I know, I watched it. It was fabulous. Yeah, it’s fantastic. Highly recommend it.

BA: Thank you, thank you. I offer that to anyone else who is following your path, too. It’s a very brief summary of this history. I’m retired but I can write postcards to hopefully influence the elections of people who are aware of injustice of all sorts. Injustice against each other, injustice against the planet. I think some of the things that I’m particularly fearful of now are the criminalization of abortion. I’m old enough to remember when friends of mine had abortions on kitchen tables, and I myself flew to Japan when I was 20 because that was one of the only places on earth other than Sweden where abortion was legal at the time, and my husband was insisting on it. So I’ve come a long way.

It’s very very important to also relax and take care of ourselves and accept the gifts that the trees and the beauty that remains in in the world can give us, and the inspiration we get from each other. I can’t tell you how great it is to know you. “There’s this woman in my class, wow, you should meet her oh my gosh!” And I know what you were up against because you shared it, and it resembled something I was up against when I was 17. I needed to leave the church I’d been raised in, and I had no one to talk to about it, so it was just rebellion, transgression, and rebellion and transgression are very helpful but they don’t offer many soft places to land.

AA: Well I was going to say one thing that gives me hope is knowing what to do in the face of it, and I again was so inspired by what you said when you encountered these horrible stories that just really shook you. Instead of running from it, you ran straight toward it and you got on a plane and flew over there and said, “I want to know. I want to interview women. I want to go to the restaurants where this happened, in the hotels. I want to see it. I will literally walk into a war zone to tell these people’s story.” And the fact that then you were able to keep speaking, and that a person could be in your audience who it turned out could then understand it better, and then he could be in a position where he could improve things, and then you published the book, and then it got into a person’s hand who could make a difference at the UN, and now rape is recognized as a weapon of war and a crime against humanity.

The fact that you were just writing your notes on the backs of envelopes and talking to whomever you could talk to, kind of like on the weekends when you weren’t working your regular gig as a literature professor, but that you were fitting it into your life because you felt this calling to do it. I think that’s the most impressive and inspirational takeaway for me, is to remind myself to do what I can even if it seems really small and even if I don’t necessarily know where it’s leading. But to think, “I want to tell this story and I want to understand and I want to dig into it more instead of running away, even if it’s really, really uncomfortable, even if it makes me cry, even if it shakes my faith, even if it shakes my concept of what it means to be human.” To run toward that because it’s really empowering, too, and we can change ourselves and deconstruct the patriarchy that we have inside our own brains. But then also, whomever we come in contact with, we can have that effect on them, too and you’re such an example of that Beverly. I’m so proud to know you, and so grateful for your example, and I want to thank you for having this conversation with me today. I learned a ton, and it was just so lovely to be with you. So thank you for being with us.

BA: You’re so welcome, Amy. Thank you for inviting me. Lots of love.

we can do something

one step at a time

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!